BY: SUSAN GIBSON, M.A., M.B.A.

In his wartime speech on rebuilding the bombed-out House of Commons, former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill observed, "We shape our buildings and afterwards our buildings shape us." We have found Churchill's words ring very true at Saint Alphonsus Regional Medical Center in Boise, Idaho, as we follow our blueprint for development into the 21st century.

In 1999, Saint Alphonsus embarked on an initiative to create a vision for the transformation of our healing ministry to meet the needs of our community into the future. That board-led process, based on extensive research, led to the creation of Vision 2010. An essential element of that vision was "advanced healing," a concept that encompasses leveraging advances in technology and practice, highly competent staff, patient-centered culture and a healing environment.

The concept led us to build the Center for Advanced Healing, which opened in 2007. It is a 400,000-square-foot, medical, surgical and critical-care tower designed not only to embody advanced healing but also to express our mission "to heal body, mind, and spirit." In shaping a physical space and the elements within it to create such a healing environment centered on the needs of the patient, we saw patient outcomes improve — and we found, as Churchill said, that we, ourselves, were shaped. So much so that we have carried the advanced healing concept into all the building and renovation we have done in other parts of the hospital.

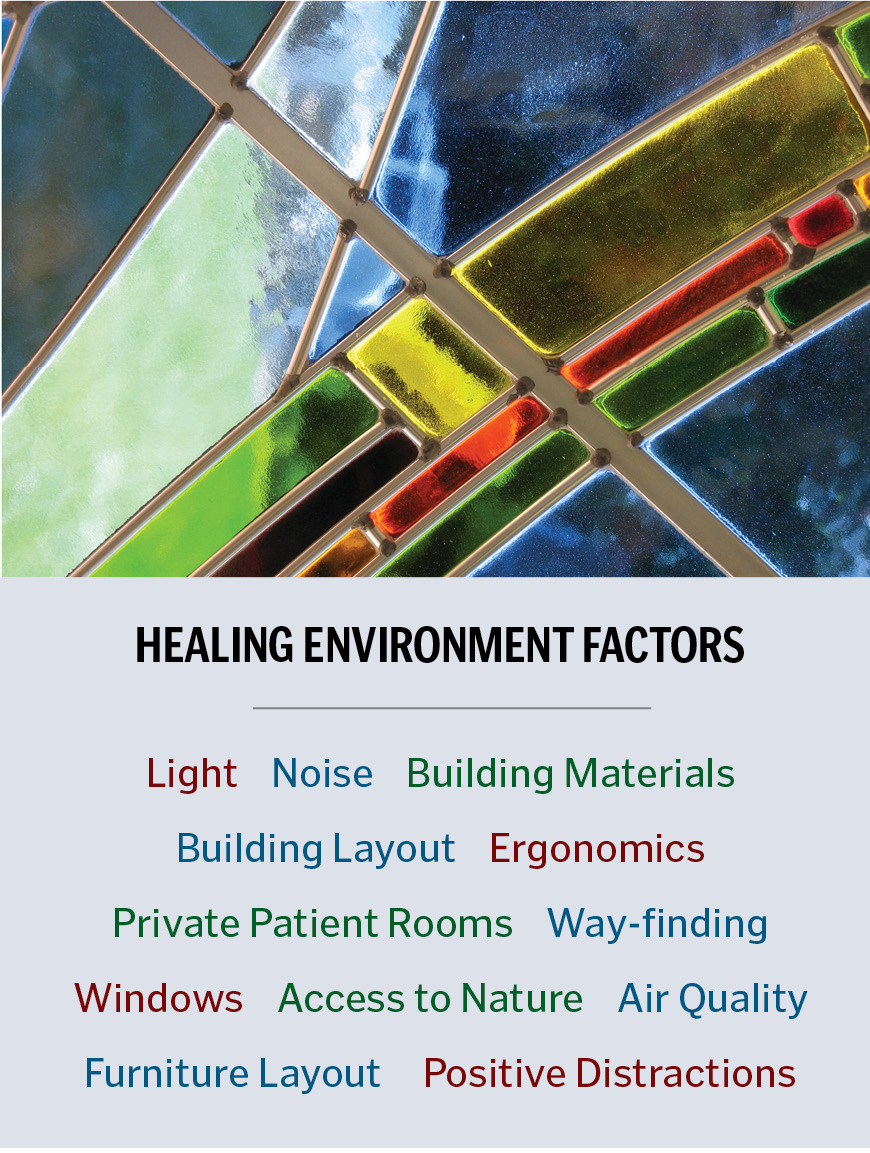

From the earliest stages of planning the Center for Advanced Healing, we spent time researching and reflecting on the impact of design components on patient, family and staff well-being. One of the first steps we took was to join the Pebble Project, a program the California-based Center for Health Design established to promote the creation of effective, evidence-based health care environments. We integrated the findings of many studies that identified the key elements of a healing environment, such as access to nature, light, quiet, privacy and positive distractions.1 As architects, administrators and caregivers worked together to design the center, we constantly reflected on the experience of the patient and family.

On several occasions, we took our questions directly to them. That's how we learned families would rather have a sleeper sofa than a desk in a patient's room; that patients much preferred gazing up at a ceiling decorated with an image of a cloud-filled sky while they were lying there awaiting radiation therapy. In our cancer center, a depiction of the sky dotted with hot air balloons is so loved by patients and staff that it is now considered standard of care.

Such input directly from our patients and caregivers, along with what we learned from our prototypes and the Pebble Project about healing environments and evidence-based design, helped us with the kind of knowledge that psychologist Edward S. Reed describes as "ecological," that is, the understanding "that all human beings acquire from their environment by looking, listening, feeling, sniffing and tasting."2

We designed and redesigned. We changed the initial construction layout midstream when we realized that the windows of many rooms looked out at the walls of other buildings, because our intuitive "ecological" sense — and the research — had taught us that views of nature can actually improve patient outcomes.3

Thus, Saint Alphonsus patients enjoy healing views of the beloved Boise foothills or the distant mountains from many windows. We created healing gardens designed to engage the senses with beautiful color and texture, sounds such as rustling leaves or fountains, the fragrance of flowers or foliage, the comfort of sunlight or shade, a place to rest or walk. Our gardens include five small gardens along our Wellness Trail, a rooftop garden, the chapel garden and a children's garden outside the Family Maternity Center.

The rooftop garden might have been beyond the reach of some patients if we had not taken the innovative step of appointing an ICU nurse to a new, full-time position of clinical integration manager for the master facility plan. Assigned to monitor the impact of every detail of patient care down to the location of electrical outlets, it was the clinical integration manager who discovered during construction that an equipped medical bed could not fit easily through the garden doorway. We modified the entrance, and now even intensive-care patients can be taken there to benefit from the spirit-lifting experience of fresh air and nature's beauty.

Positive distractions are an important component of providing a healing experience for patients and families caught up in the pain and stress of illness. Thoughtful integration of art into the environment can provide such a distraction — and so much more. The integration of art into our environment began early in the design phase when appropriate settings for art were carefully identified and included.

Through the Pebble Project, we were able to gain access to a body of research on appropriate art for care settings.

We incorporated these studies into our art principles and selected an art consultant who appreciated the uniqueness of the health care environment and helped us find regional artists. Their work has delighted our patients and visitors and provided conversational connections between patient and caregiver.

We anticipated art also could serve as a way-finding clue in an unfamiliar environment, so we built art niches with distinctive displays in each elevator lobby. Families visiting our ICU call that floor the tea-pot floor because they know when the elevator door opens and they see a collection of tea pots in niches, that's where to step out. Tea pots have other layers of meaning; we hope the homey display helps transport imaginations to a more tranquil, healing place.

Our art collection incorporates many pieces reminding people of our Catholic heritage and its role in the healing ministry, as well as pieces and spaces that reflect the spirituality of other faith traditions. Images of Our Lady of Guadalupe and the Black Madonna convey not only our Catholic foundation, but also our respect for diversity. Landscapes nurture the creation-centered spirituality of the Mountain West, and figurative pieces reflect the lives of the people who come to us for care.

The carefully designed Holy Cross Chapel, prominently located on the first floor near the front entrance, provides quiet space for patients, visitors and staff. Although our chapel is definitely a Catholic chapel, we tried to make it an appealing space for those of other faiths, partially through art. It includes a chapel garden for those who root their spirituality in nature.

Saint Alphonsus was founded in 1894 by the Sisters of the Holy Cross. An entire wall in a busy, second-floor corridor adjacent to the cafeteria and the surgery waiting room is dedicated to the history of Saint Alphonsus and the role it has played for over 100 years in service to the community. The Heritage Wall also incorporates references to local history among its pictures and three-dimensional objects.

PRIVATE SPACES, FUNCTIONAL PLACES

Patients and families experiencing serious illness need both privacy and spaces where they can be together or in which to find solitude. For patients, volumes of research demonstrate the positive impact of private rooms on patient outcomes. Single rooms provide privacy and quiet for the personal and taxing experience of hospitalization. Paradoxically, private rooms also address the social needs of patients; evidence shows that families spend more time with hospitalized loved ones in private rooms. In addition, patient-nurse interaction is enhanced by the privacy of single rooms. Family members also benefit from the opportunity to communicate with staff in a private setting.

For families, waiting rooms, particularly in critical care areas, provide warmth and amenities. These large spaces are designed with fireplaces, business areas and refreshment centers. Partial walls and glass panels divide the rooms into clustered seating areas where families gather. On medical-surgical units, waiting rooms and private reflection rooms are used by families who need a respite from the patient room to pray, grieve or gather with other family members.

In many ways, the needs of caregivers in the patient care environment mirror those of the patient and family. Patient care is physically and emotionally demanding work that calls for the availability of a healing environment. The design of nursing units in the Center for Advanced Healing involved nurses at every stage of the process. The clinical integration manager's oversight ensured that equipment and even electrical outlets were not only convenient, but ergonomically placed. Charting stations and supply spaces were dispersed to patient rooms, saving steps and keeping nurses close to patients.

Patient care is also a team effort requiring spaces for the care team to gather, consult and provide mutual support. Centralized nurses' stations and conference rooms on every unit provide that space. Break rooms with lockers, mini-kitchens and comfortable seating provide a place for informal interaction. On most units, these break rooms have windows, giving access to natural light. A recent initiative tucked relaxation spaces with massage chairs, fountains and music into spaces throughout the facility, providing respites for tired caregivers.

Saint Alphonsus embarked on the construction of the Center for Advanced Healing and a patient-centered culture transformation at the same time. We found that the two initiatives shaped and informed one another. The work of Kirk Hamilton, an architect who has studied organizational development, posits that facility design and culture change efforts are most effective when they are undertaken simultaneously. "The organization's environment, and therefore its design, can be a crucial enabler of desired behavior or it can be a barrier to the desired behavior and play a powerful role in presenting the intended culture."4

Ecological psychologists such as Roger Barker describe the mutual impact of the social milieu and the physical environment as behavior settings.5 Saint Alphonsus experienced the effects of such a behavior setting in evaluating a prototype unit. During the planning of this unit, carpet, ceiling tile and other materials were selected for their noise-absorbing properties in an effort to create a quieter, more tranquil environment. When the unit opened, the decrease in noise levels was dramatic. As researchers measured noise levels and compared them to a similar unit, they also noticed differences in staff behavior. Everyone spoke and moved more quietly. Noisy people and equipment elicited frowns that usually stilled the offenders.

The process of designing and constructing the center required intense planning and commitment of time and resources. Although we believe the total impact of the simultaneous culture and healing environment initiatives cannot be measured numerically, we have ample evidence of the results in our significantly improved patient satisfaction scores. Although our nursing engagement scores do not specifically address the physical work environment, the new facility appears to have played a part in improving year-to-year results. Many of the letters we receive from patients and families also express their appreciation of the physical environment.

HEALING ENVIRONMENT: LESSONS LEARNED

We set out to shape a healing environment and, in turn, that environment shaped us. As we reflect on what we have accomplished, we are aware of many lessons learned:

- Begin early. Every stage of design construction offers opportunities to shape a more healing environment. The building layout, finishes and furnishings, outdoor environment and art can all be tools for healing. Design with the end in mind.

- Pay attention to evidence-based design. Become a member of the Pebble Project or access the growing body of knowledge on the Center for Health Design website (www.healthdesign.org).

- Develop a philosophy of design, incorporating your priorities.

- Choose design professionals, architects, designers and art consultants who understand your philosophy.

- Ensure that an influencer with knowledge of healing environment principles is at the decision-making table.

- Involve patient-care staff in decisions at all stages. Consider designating a clinician to oversee attention to clinical details.

- Seek input from patients and families about what makes a difference to them.

- Consider testing design on a small scale. Incorporating key ideas into the renovation of one prototype unit offers an opportunity for learning in action.

- Creating a healing environment is possible at many different budget levels. The most important factors are the time and attention given to reflection on the patient experience.

NOTES

- Roger Ulrich et al., "The Role of the Physical Environment in the Hospital of the 21st Century: A Once in a Lifetime Opportunity" (report for the Center for Health Design, Sept. 2004), http://www.healthdesign.org/research/reports/physical_environ.php.

- Edward S. Reed, The Necessity of Experience (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1996), 2.

- Roger Ulrich, "View through a Window May Influence Recovery from Surgery," Science 27 April 1984: 420-421.

- D. Kirk Hamilton and Robin Orr, "Cultural Transformation and Design" in Improving Health Care with Better Building Design, Sara O. Marberry, ed. (Concord, CA: Health Administration Press, 2005), 145-60.

- Phil Schoggen, Behavior Settings: A Revision and Extension of Roger C. Barker's 'Ecological Psychology' (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1989).

SUSAN GIBSON is vice president of mission services at Saint Alphonsus Regional Medical Center, Boise, Idaho. She served on the steering committee for the Saint Alphonsus Regional Medical Center master facility plan and chaired the project's healing environment committee.

ART THAT BENEFITS PATIENTS

In a health care setting, the first rule is to do no harm. While good art can be very challenging or provocative, in a hospital setting, it should reduce stress. The studies demonstrate that patients prefer and benefit most from positive images and have a strong bias toward landscapes, particularly familiar scenes that provide an imaginative escape. Scenes should be calm, not stormy; verdant and spring-like, rather than bleak. Figurative art should show positive, nurturing images of people.

Avoid "ambiguity or uncertainty, emotionally negative or provocative subject matter, surreal qualities, closely spaced repeating edges/forms that are optically unstable or appear to move, restricted depth or claustrophobic-like qualities, close-up animals staring directly at the viewer; and outdoor scenes with overcast or foreboding weather."

Roger Ulrich and Laura Gilpin, "Healing Arts: Nutrition for the Soul" in Designing and Practicing Patient-Centered Care: A Practical Guide to the Planetree Model, eds. S. Frampton., L. Gilpin and P.A. Charmel (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2003).

Copyright © 2010 by the Catholic Health Association of the United States

For reprint permission, contact Betty Crosby or call (314) 253-3477.