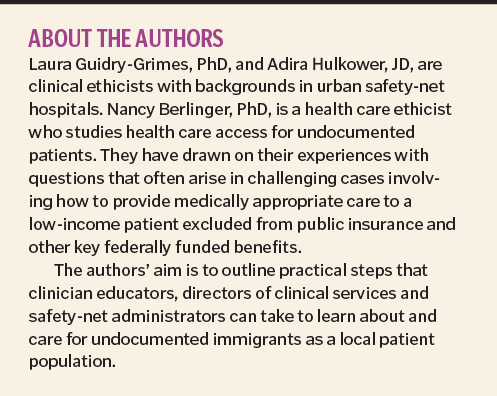

BY: NANCY BERLINGER, PhD, LAURA GUIDRY-GRIMES PhD and ADIRA HULKOWER, JD

Alex Nabaum

Immigration policy and health care — what's the connection? Safety-net hospitals, community health centers and health programs serving low-income populations almost inevitably will encounter undocumented immigrants:

- As patients or prospective patients

- As community members for whom health care access is an important avenue for integration into American society

- As persons whose health-related legal rights may be overlooked, imperiled or difficult to use

Knowing how this vulnerable group is similar to — and different from — other low-income patient populations is an important part of planning for and providing good care. A health care facility's administration, staff and clinicians should be educated and ready to take practical steps to protect the basic rights of these patients, manage typical challenges in their care and strengthen the safety net. In the words of Rob Marlin, a Cambridge, Mass., physician who trains colleagues to care for their immigrant patients, physicians and safety-net institutions need to have "greater knowledge of immigration policy to take care of our patients … [policy] is no longer a spectator sport."1

Federal immigration policies currently put a priority on enforcement and deportation via the operations of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). Undocumented immigrants try to avoid situations where their status might be scrutinized, including contact with police, security guards and other authority figures. Because security and information-gathering are features of safety-net health care facilities, immigrants may avoid the settings. "Many undocumented immigrants and their families therefore go without needed care, to their detriment and sometimes that of others, as in the case of a woman with syphilis who is pregnant with a future U.S. citizen," wrote Kathleen R. Page, MD, and Sarah Polk, MD, MH, in a March 2017 New England Journal of Medicine article.2 The pregnant woman had been diagnosed at the Baltimore City Health Department and urged to return to the clinic for treatment. She agreed, but didn't show up. An outreach team contacted her, and she explained that she had gone to the clinic but saw an armed security guard, and "because I have no papers, I left."

SAFETY-NET OBLIGATIONS

Safety-net institutions — including public hospitals and clinics, nonprofit community health centers such as Federally Qualified Health Centers and nonprofit hospitals with emergency departments — share a basic duty of care to patients who lack health care access for reasons that include lack of insurance.

Federal law provides some health care access through the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA) of 1987.3 This law ensures that all patients who come to an emergency department for medical care will receive appropriate medical screening, and if found to be experiencing a medical emergency (or in active labor), they will be treated until their condition is stable. Hospitals can apply to state emergency Medicaid programs for reimbursement for specified emergency treatments provided to uninsured patients admitted under EMTALA. Also, federal funding of FQHCs supports low-cost primary care for patients who lack insurance.

But undocumented immigrants are broadly excluded from federally funded insurance programs such as Medicare, Medicaid, the Child Health Insurance Program and Affordable Care Act insurance subsidies. Because of these exclusions, an uninsured patient who is undocumented has severely limited — or nonexistent — access to outpatient diagnostic, specialty, rehabilitative, chronic and palliative services, including supplies and equipment, even when the need for these services follows from successful emergency or primary treatment.4

State Medicaid programs and local (city or county) health care systems can invest in services for undocumented uninsured immigrants to partially compensate for the federal insurance exclusions. These programs vary widely across states and cities. A few states, such as California, New York and Massachusetts, have enacted laws and policies to provide access to state-funded insurance to eligible undocumented immigrants.5 Some major cities, including New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco, have programs that offer care coordination plus low-cost primary care to low-income uninsured residents.6

DO PROVIDERS NEED TO ASK ABOUT STATUS?

There usually is no medical need or legal requirement to ask about a patient's immigration status before initiating medical treatment. However, in the American health care system, asking about a patient's insurance status is typical, including after the initiation of emergency treatment.

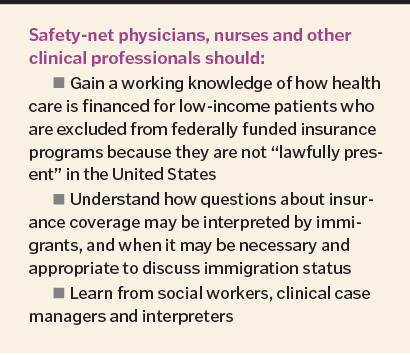

When a patient lacks proof of insurance from a private insurer or a public insurer such as Medicare or Medicaid, the next step often is for a medical social worker or clinical case manager to determine whether the patient is eligible for public insurance and to help him or her sign up, or explore other payment arrangements. Clarifying that an uninsured patient is ineligible for Medicaid or other insurance is a necessary step before applying to a state's emergency Medicaid program for reimbursement.

That's when the patient's immigration status may come to light. Undocumented immigrants (and often, other immigrants) are wary about being asked for information that may reveal immigration status. Therefore, providers responsible for discussing payment with patients should be prepared to explain why they are asking about insurance eligibility, namely, with the goal of securing health care access.

Also, an undocumented patient may choose to directly disclose his or her immigration status to a trusted health care professional. Being undocumented is often a highly stressful experience. Safety-net hospitals can draw on their own social workers and case managers as resources in clinician education. These staff members can offer firsthand descriptions of how they provide psychological support and talk with uninsured patients to determine if they are eligible for Medicaid or other insurance, including when immigration status is a relevant factor. Such information can help other clinicians understand the undocumented patient's perspective and concerns.

Certified medical interpreters may be additional resources for professional education, because they are frequently involved in the care of immigrant patients and their families. In turn, interpreters may benefit from attending clinician education about the rights, needs and concerns of immigrant patient populations.

Education is key to helping care providers understand undocumented patients' needs and rights — for example, how much information about immigration should be included in a patient's chart, given that charts potentially are discoverable.7 Education is equally important for helping providers recognize and navigate their own questions and concerns regarding this vulnerable patient population.

COPING WITH POLICY CONSTRAINTS

Cases involving undocumented patients can elicit staff frustration and distress when medical needs could be resolved or more effectively managed if patients had access to some benefit available to other low-income patients. These feelings can trigger workaround behaviors, such as "tailoring the chart" or "bending the rules" to secure resources for a patient. Safety-net professionals may benefit from periodic opportunities to discuss typical ("this happens every day") and less common problems. Talking openly about cases involving undocumented patients and the emotions the cases create among caregivers can help safety-net professionals acknowledge their own moral and other subjective intuitions about individual patients or types of cases.

Clinical and administrative professionals in safety-net settings also need access to reliable, regularly updated sources of information on the legal rights of their undocumented patients.8 Two good information sources are the National Immigration Law Center and the Undocumented Patients Project of The Hastings Center, a nonpartisan bioethics research institution based in Garrison, N.Y.

The National Immigration Law Center's website offers detailed, plain-language information on undocumented patients' rights, plus guidance for health care providers on dealing with immigration officials and law enforcement.9

The Hastings Center's "Quick Guide" to help professionals get up to speed on state and local issues and services relevant to the care of undocumented immigrants includes information about medical-legal partnerships available in 41 states.10 Medical-legal partnership attorneys provide legal services to patients and frequently collaborate with health care professionals on immigration issues.

GUIDANCE ON RESOURCE ALLOCATION

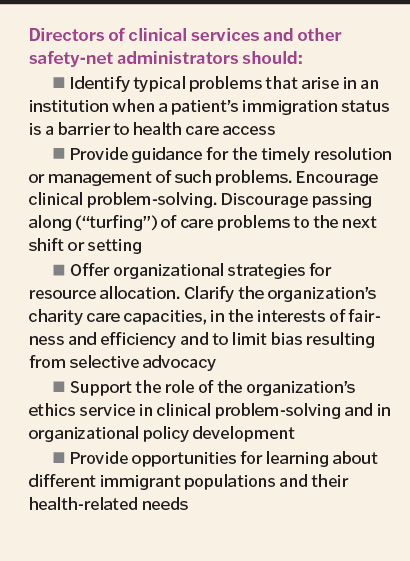

To avoid raising unrealistic expectations among low-income patients and their families — including individuals who are undocumented — safety-net professionals deserve clarity about what a system will provide based on patient need. Which resources are allocated case by case, and what is the process for allocating the resources?

For example, will a hospital agree to retain a seriously ill patient so that the patient can receive a life-sustaining treatment that would be difficult or impossible to obtain in a non-hospital setting due to lack of insurance?

How should cancer care for undocumented immigrants be planned?

Clarifying typical as well as occasional problems helps clinical leaders, starting with unit-level managers and chiefs of clinical services, to frame potential institutional solutions and make the case for these solutions in a coordinated way. Even if solutions remain elusive, such discussion can help point toward opportunities for improvement and reform.

A trustworthy facilitator is essential so that clinicians can speak freely and so they can safely challenge one another's judgments and actions. They also should be willing to take clinical insights and recommendations for the appropriate care of undocumented immigrants up the line if some typical problem has a feasible institutional solution.

For example, clinicians' observations and informal data collection may suggest a better way for a local public health system to invest in services or how to better align a state's emergency Medicaid provisions with patients' needs. Other benefits of a shared institutional framework include the avoidance of duplicate, siloed efforts in different departments.

A shared framework should recognize that, especially in hospitals, responsibility for problem solving often will be distributed across shifts as team members rotate on and off. Clinical hand-offs should prepare incoming team members for ongoing collaboration to resolve or manage medical, social and legal issues during hospitalization and discharge planning.

THE ROLE OF THE ETHICS SERVICE

Hospitals long have been required to have some mechanism for resolving ethical challenges. In many institutions, it takes the form of clinical ethics consultation on individual cases, plus an ethics committee and ethics education activities. The ethics service has the potential to play key educational, fact-finding and policy development roles concerning health care access for undocumented immigrants, including outreach to community health centers that serve the same patient population but are less likely to have an in-house ethics operation.

For example, the ethics service may identify challenging cases that can be used for teaching and learning. Convening discussions about health care access for undocumented immigrants within a multisite organization, and with colleagues at different institutions serving the same community, are two further actions that an ethics service can take to support clinical understanding, well-informed organizational policymaking and greater justice in health care.

CONCLUSION

Throughout the world, unprecedented numbers of people are relocating from poorer to wealthier and from dangerous to relatively safer regions. Safety-net health care professionals in the U.S. benefit from a basic understanding of the health care needs and legal rights of refugees, asylum seekers, survivors of torture, ICE detainees and people who have been trafficked, in addition to undocumented immigrants and recent authorized immigrants.11 These populations overlap with the undocumented immigrant population but are distinct in some respects. Opportunities for clinician education in a safety-net institution should include attention to different immigrant populations it serves. Providing clinicians with a pocket card or other tool that lists all in-house resources for providing health care to immigrant patients —including medical-legal partnerships (MLPs) that may provide in-house legal assistance in such cases12 — would be a practical demonstration of an institution's support.

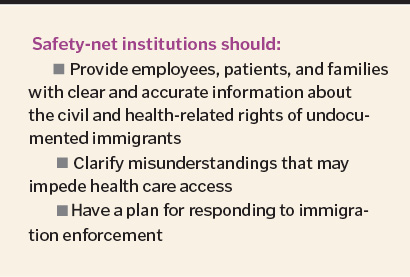

Safety-net health care systems are major employers. They have broad educational responsibilities to staff members, to professionals employed under contract and to some nonstaff, such as community physicians with admitting privileges. All employees should recognize and agree to respect the duties of a health care institution to its patients, including their civil rights as persons.

Professionals responsible for employee education via a clinical service or an administrative department such as human resources should ensure that all employees have opportunities to learn about the health-related rights and constitutional rights of undocumented immigrants and other noncitizens under current U.S. law.13

The health care workforce is large, and turnover is frequent. Myths or misinformation about the rights of undocumented immigrants can take hold and spread informally. Employee education should aim to clarify common misunderstandings. For example, the medical records privacy protections of the Federal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 apply to all patients regardless of immigration status; knowing or suspecting that a patient is undocumented creates no obligation to inform federal immigration authorities.

Professional education should teach and reinforce information about health care access for undocumented immigrants and how it applies to safety-net health care. Such instruction should take place during regular opportunities, such as new staff orientation, and should ensure that unit-level supervisors and individual staff members know where to turn as questions arise in everyday work. E-learning modules can be an effective means of providing information across an institution's workforce.

Educators in safety-net systems should further aim to ensure that information about the health-related rights and constitutional rights of patients, regardless of their immigration status, is available in appropriate languages and formats to patients, family members and community organizations serving immigrants. This is a community service, and it also helps facilitate referrals. Public health systems also may create and share informational resources that describe immigrants' rights and services under local and state law and federal protections; these resources, if they exist locally, can be shared with patients, families and employees.

NANCY BERLINGER is a research scholar at The Hastings Center in Garrison, New York. She co-directs the Undocumented Patients project, www.undocumentedpatients.org, a hub for analysis, policy solutions and tools concerning health care access for this population.

LAURA GUIDRY-GRIMES is a clinical ethicist at Medstar Washington (D.C.) Hospital Center. In July 2017, she will become an assistant professor in the Division of Medical Humanities at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, in Little Rock.

ADIRA HULKOWER is a bioethics consultant at Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, New York.

The authors acknowledge the assistance of Norine McGrath, MD, FACEP, director of the John J. Lynch, MD Center for Ethics at Medstar Washington Hospital Center, who read and provided comments on this article in draft.

NOTES

- Quoted in Elisabeth Poorman, "Caring for Immigrant Patients When the Rules Can Shift Any Time," CommonHealth/WBUR (Feb. 21, 2017), www.wbur.org/commonhealth/2017/02/21/immigration-concerns-exam-room (accessed May 9, 2017).

- Kathleen R. Page and Sarah Polk, "Chilling Effect? Post-Election Health Care Use by Undocumented and Mixed-Status Families," New England Journal of Medicine, (March 23, 2017). Online ahead of print: www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp1700829 (accessed May 9, 2017).

- Michael K. Gusmano, "Undocumented Immigrants in the United States: U.S. Health Policy and Access to Care," The Hastings Center/Undocumented Patients Project, (March 15, 2012), http://undocumentedpatients.org/issuebrief/health-policy-and-access-to-care/ (accessed May 9, 2017).

- Nancy Berlinger, "Undocumented Immigrants and Access to Rehabilitation Services: Safety and Harm in the Aftermath of Occupational Injury," PM&R 9, no. 6 (June 2017): 408-10.

- On PRUCOL and eligibility for state Medicaid in California, see: "Medi-Cal's Non-Citizen Population," Medi-Cal Statistical Brief, October 2015, www.dhcs.ca.gov/dataandstats/statistics/Documents/noncitizen_brief_ADAfinal.pdf (accessed May 9, 2017).

- On initiatives by major American cities, see: Nancy Berlinger, Claudia Calhoon, Michael K. Gusmano and Jackie Vimo, Undocumented Patients and Access to Health Care in New York City: Identifying Fair, Effective, and Sustainable Local Policy Solutions: Report and Recommendations to the Office of the Mayor of New York City (New York: The Hastings Center and the New York Immigration Coalition, April 2015) http://undocumentedpatients.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Undocumented-Immigrants-and-Access-to-Health-Care-NYC-Report-April-2015.pdf (accessed May 21, 2017). New York City's direct-access program is now known as ActionHealthNYC.

- Jennifer Adaeze Okwerekwu, "Why I've Learned to Leave Blank Spots in Some Patients' Medical Records," Stat News (March 6, 2017) www.statnews.com/2017/03/06/immigrants-undocumented-doctors/ (accessed May 9, 2017).

- Jasmine C. Lee, Rudy Omri and Julia Preston, "What Are Sanctuary Cities?" New York Times, Feb. 6, 2017. www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/09/02/us/sanctuary-cities.html?_r=0 (accessed May 21, 2017).

- National Immigration Law Center, "Is It Safe to Apply for Health Insurance or Seek Health Care?" www.nilc.org/issues/health-care/health-insurance-and-care-rights/ (accessed June 7, 2017). See also, National Immigration Law Center, "Health Care Providers and Immigration Enforcement: Know Your Rights, Know Your Patients' Rights" www.nilc.org/issues/immigration-enforcement/healthcare-provider-and-patients-rights-imm-enf/ (accessed June 7, 2017).

- Rachel Zacharias, "Quick Guide to State and County-Level Data and Resources: Undocumented Patients in the Local Safety Net," The Hastings Center/Undocumented Patients Project (June 7, 2017), http://undocumentedpatients.org/issuebrief/undocumented-patients-in-the-local-safety-net-tools-for-teaching-learning-and-practice/ (accessed June 7, 2017).

- Refugee Health Assessment clinics or programs may be available in a community. On the health-related rights and needs of refugees and asylum seekers, see: Nancy Kass, "Ethics, Refugees, and the President's Executive Order," American Journal of Bioethics Blog (Feb. 21, 2017), www.bioethics.net/2017/02/ethics-refugees-and-the-presidents-executive-order/ (accessed May 9, 2017).

Of survivors of torture, see The National Consortium of Torture Treatment Programs, http://www.ncttp.org/ (accessed May 9, 2017).

Of Immigration Control and Enforcement (ICE) detainees, see: Human Rights Watch and Community Initiatives for Visiting Immigrants in Confinement (CIVIC), "Systematic Indifference: Dangerous & Substandard Medical Care in U.S. Immigration Detention," May 8, 2017. Full report: https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/report_pdf/usimmigration0517.pdf (accessed May 9, 2017).

Summary: https://www.hrw.org/report/2017/05/08/systemic-indifference/dangerous-substandard-medical-care-us-immigration-detention (accessed May 9, 2017).

Of people who have been trafficked, see: Corinne Schwarz et al., "Human Trafficking Identification and Service Provision in the Medical and Social Service Sectors," Health and Human Rights Journal 18, no. 1 (June 2016): 181-92. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5070690/pdf/hhr-18-181.pdf (accessed May 9, 2017).

Wendy Macias-Konstantopoulos, "Human Trafficking: The Role of Medicine in Interrupting the Cycle of Abuse and Violence," Annals of Internal Medicine 165, no. 8 (Oct. 18, 2016). - National Immigration Law Center, "Is It Safe to Apply for Health Insurance or Seek Health Care?"

- National Immigration Law Center.