Michael P. Panicola, Ph.D.

Corporate Director,

Ethics and Social Responsibility

SSM Health Care

St. Louis

[email protected]

Ron Hamel, Ph.D.

Senior Director, Ethics

Catholic Health Association

St. Louis

[email protected]

Requests for treatment deemed medically inappropriate, often referred to as requests or demands for "futile treatment," constitute one of the most intractable ethical challenges in the care of patients. Various attempts to address the issue go back well over 20 years. Yet despite this it seems as if very little progress has been made in preventing, reducing, or successfully resolving these situations.

Jeffrey Burns and Robert Truog, in a 2007 article in Chest, describe three generations of efforts to deal with medical futility.1 The first is characterized by attempts to define futility. One author proposed seven clinical conditions in which further treatment should not be provided.2 Another proposed a distinction between "qualitative" futility (based on a quality-of-life judgment) and "quantitative" futility (involving a judgment about what is a reasonable likelihood of the treatment's success).3 And yet another recommended limiting the concept of futility to treatments that are "physiologically" futile, that is, they are unable to attain their physiologic goal.4 Burns and Truog note that there are serious difficulties inherent in each of the definitional approaches and that they were largely unsuccessful in resolving many of the more challenging cases. For these reasons, clinicians and ethicists, by the late 1990s, abandoned this attempt and sought alternatives.

This led to the second generation of the futility debate which consisted in the development of procedural guidelines to resolve disputes over medically futile treatment. A consortium of Houston-based hospitals offered the first such procedural approach, but the approach quickly gained in popularity and spread rather quickly to other areas of the country.5 In 1999 it was endorsed by the American Medical Association.6 Many policies in hospitals across the country reflect this approach. Typically, the procedural guidelines are invoked as a last resort and they attempt to ensure that all voices are heard by the Ethics Committee. They also usually identify options for moving forward.

Texas, along with a few other states, has incorporated the procedural approach into law.7 In addition to embodying the key elements typical of procedural approaches, the Texas Advance Directives Act (1999) mandates a 10-day waiting period between a decision of the Ethics Committee affirming medical futility and the actual withdrawal of treatment. The Emilio Gonzales case in 2007, however, revealed weaknesses in the procedural approach, especially in a legislated form. The case sparked a state-wide, often contentious, debate about the legislation. Right-to-life and disability groups in particular advocated for changes in the legislation which have not yet occurred.

Burns and Truog maintain that neither first nor second generation attempts to address the matter of medical futility have been successful. What they propose as an alternative is better communication between clinicians and patients or their surrogates and the use of mediation techniques to resolve differences when disputes arise. The goal, they say, is to "mitigate conflicts as they arise but before they become intractable."8 Underlying their approach is the belief that most futility cases are the result of breakdowns in communication and trust. Hence, they urge improvement in clinicians' communication skills and suggest a four-step approach to negotiation.9 Recognizing that good communication and attempts at negotiation do not always work, they suggest going to court to seek appointment of another surrogate if the patient is being harmed by a surrogate's decisions. Short of that, they recommend acquiescing to surrogate's requests.10 Because of the potential negative impact on the morale of health care professionals, toleration of requests for treatment deemed to be futile should be accompanied by support for those who continue to care for these patients, rather than try to overrule requests for medically inappropriate treatments. The authors consider their approach to the problem to constitute the third generation approach to medical futility.

In a fairly recent article in the Annals of Internal Medicine, Timothy Quill and colleagues, while not explicitly referring to this third generation approach, articulate a communication-centered tact to "patients who want 'everything.'"11 In many ways, the work of Quill and colleagues provides content to Burns' and Truog's urging of better communication by clinicians. They suggest six steps in dealing with requests to do everything: 1) understand what "doing everything" means to the patient; 2) propose a philosophy of treatment consistent with the patient's values and priorities and the physician's assessment of the patient's medical condition and prognosis; 3) recommend a plan of treatment consistent with the patient's treatment philosophy; 4) support emotional responses of patients and families to difficult conversations; 5) negotiate disagreements, looking for common ground and new solutions; 6) use a harm-reduction strategy for continued requests for burdensome treatments that are very unlikely to work.12

Also in the mode of a "third generation approach" is the recent work of SSM Health Care, a large Catholic health care system based in St. Louis, MO. The evolution of SSM Health Care's work in this area mirrors the three generations of futility described above. Based on data collected from ethics consultations over a five-year period (1998-2003), SSM Health Care saw a significant increase in cases grouped under the category "futility" at their acute care facilities. Like others, SSM Health Care first attempted to define futile treatment and list conditions for which certain treatments generally would be deemed medically inappropriate. The hope was that these conditions would form the basis for which treatment requests could be denied on futility grounds.

The effort proved unsuccessful because no consensus could be reached on what conditions qualified for no treatment, except for anencephaly and even then there were debates about which treatments could be deemed futile. As a result, SSM Health Care shifted course, attempting instead to outline a futility policy with procedures that could help physicians and other caregivers better manage situations where patients or, more typically, their families requested medically inappropriate treatments. While such policies were established, this approach, too, ultimately failed because it did nothing to reduce the number of conflict situations that arose and physicians, fearful of litigation, felt as though they had no legal coverage like that afforded under the Texas Advance Directives Act. The practical result was that the policies and their procedures were not followed as physicians usually ended up acquiescing to requests for treatment that they considered futile.

Recognizing the shortfalls of the previous two approaches, a team of system leaders set out to understand the root causes of the increasing number of cases involving requests for medically inappropriate treatments. Through follow-up interviews after ethics consultations with physicians and other caregivers as well as patients and families, it quickly became apparent that the main source of the problem was poor/inconsistent communication and lack of coordination of care. Some of the more specific issues noted during the interviews included the following:

- Patients/families are not informed "early enough" about the seriousness of the patient's condition and are not given sufficient time to reconcile with this reality;

- Patients/families are often only given bits and pieces of information about the patient's condition/progress and sometimes conflicting information is presented by the various caregivers;

- Patients/families feel that decisions to limit treatment will result in the patient being abandoned and not receiving the same level of care and attention;

- Goals of care and specific care plans are often not established for patients and important issues sometimes go unaddressed (e.g., code status, pain and symptom management needs, patient preferences);

- Physicians and other caregivers do not communicate among themselves effectively and do not come together to coordinate the patient's care;

- No single physician is designated as the primary contact person for the patient/family;

- Physicians tend to present all treatment options as though they are equal and leave it to patients/families to decide what they want;

- Physicians tend to shy away from having difficult conversations with patients/families and do not address unreasonable requests upfront.

Most, if not all, of these issues were evident in the medical futility ethics consultations upon retrospective review. The following fictitious case is representative of the types of cases reviewed and highlights the issues noted in the interviews. An 81-year-old female patient was admitted to the hospital over two months prior to the request for an ethics consultation for an elective surgery to repair an abdominal aortic aneurysm. Endovascular aneurysm repair, which was originally planned, proved too difficult and as such an open repair was performed.

The patient initially seemed to be recovering well in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU), but starting around two weeks post-surgery she developed multiple complications, including: ischemic bowel necessitating colon resection; urosepsis requiring antibiotic therapy; multiple pneumonias leading to tracheostomy and ventilation; ischemic stroke resulting in left-side hemiplegia and cognitive deficit; disseminated intravascular coagulation (or DIC) that caused significant bleeding requiring frequent administration of platelets and fresh frozen plasma; and acute renal failure for which dialysis would be necessary. At the time of the ethics consultation, the patient was still in the ICU on mechanical ventilation at 100% oxygenation; still on antibiotics; receiving blood products every-other-day for the DIC; had a PEG tube for nutritional support; was mildly sedated for pain and rest; and had not moved her left-side. Despite repeated attempts by the intensest to persuade the family to limit some forms of treatment given the patient's overall medical condition, the family insisted that the patient continue to receive ventilation, tube feedings, blood products, and surgery as needed as well as initiate dialysis.

The family dynamics and physician interactions with the family were remarkable in this case. The patient's immediate family consisted of her husband, a daughter who lived out of town, and a son who visited everyday. The husband was very quiet, hesitant to speak up, and often deferred to his children, especially the daughter, when decisions needed to be made. He really only expressed that he wanted his wife to get better and that he did not want her to suffer. The daughter, on the other hand, was very vocal and uncompromising when it came to what she thought was best for her mother. Participating by phone for most discussions and visiting once from out of town, the daughter repeatedly insisted that "everything be done" and that the hospital or the physicians could not stop anything unless she or the family consented. The daughter talked often about "firing" certain physicians, especially the intensivist, and mentioned frequently the possibility of a lawsuit. The son, who sat by the bedside of his mother everyday for hours on end, was initially insistent that everything be done but began to moderate his stance as time went on, except when in discussions where his sister was involved.

The treating physicians were all in agreement that the patient had virtually no hope of recovering, but they were not uniform in what they communicated to the family. The intensivist, who had been overseeing the patient's care for much of her stay in the ICU, was straightforward with the family early on about the seriousness of the patient's condition and her poor chances of ever recovering. In fact, about three weeks prior to the ethics consultation, he engaged the family in earnest about stopping blood products and making the patient a DNR. The vascular surgeon, who performed the original procedure, remained active in the patient's care and often communicated to the family that they "should not give up hope," even though he told his colleagues that the patient "did not have much of a chance." The general surgeon, who performed the colon resection, also remained active in the patient's care but, like the intensivist, believed that limiting some forms of treatment was in the patient's best interests. Yet she also told the family that she would be willing to perform exploratory surgery to determine the source of the patient's bleeding if they wanted that. The infectious disease specialist, who had been called in to the case to treat the patient's pneumonia, expressed to the family her belief that further antibiotic therapy was futile and that the patient had no reasonable hope of recovery. The nephrologist, who was consulted soon after the patient's kidneys started to fail just prior to the ethics consultation, informed the family that the patient was not a viable candidate for dialysis and recommended comfort measures only.

Because of the intractable conflict that developed between the family and the physicians, especially the intensivist, an ethics consultation was requested. The consultation was successful in that it provided a forum where all the primary caregivers could come together with the family and all involved in the consultation were allowed to express their viewpoints. As far as developing a realistic care plan, however, the only item that the family agreed to was to make the patient a DNR. The end result was that the patient remained in the ICU for two more weeks, receiving all current therapies as well as the addition of dialysis three times per week, until she arrested and died. Not a single person involved in the patient's care felt right about continuing with the aggressive care plan and one nurse in particular requested to be reassigned because she could not in good conscience carry it out. Meanwhile, the family left angry and throughout the remaining weeks following the consultation grew increasingly detached from and mistrustful of the caregivers and the hospital in general. By all accounts it was a bad outcome, both in process and result.

Using the information gained through the interviews and reflecting on cases such as the one outlined above, the team of system leaders from SSM Health Care changed course, scrapping much of its previous work for a set of practice guidelines primarily for physicians and secondarily for other caregivers on enhancing communication and coordination of care. The guidelines (presented below) are divided into two main sections: the first is more educational in nature and outlines simple guidelines on how to effectively communicate and coordinate the care of seriously ill and dying patients; and the second offers additional guidelines for resolving conflict situations when they arise with an emphasis on communication and negotiation. Another element of the guidelines addressed in the first part has to do with care conferences, which have been shown to enhance communication and care coordination as well as reduce conflict situations.13 SSM Health Care is currently working with its facilities to implement care conferences throughout the system in high acuity areas. The starting point for this initiative will be ICUs where care conferences will be routine for patients with an ICU length-of-stay >5days, a high mortality risk, 3+ specialists involved in the patient's care, a significant change in condition, OR (not and) whose family member or caregiver requests one. Hard data have yet to be obtained as to whether the guidelines and routine care conferences result in fewer situations involving requests for inappropriate medical treatments. However, the anecdotal evidence is compelling as the number of ethics consultations around the system categorized as "futility" has dipped from 37 in the two quarters prior to the release of the guidelines to just 8 over the five months since the guidelines have been widely disseminated throughout the system. Additional data are necessary to validate the efficacy of this approach but at this point there is reason to be encouraged. Below are the guidelines as they have been shared throughout SSM Health Care along with a tool for conducting care conferences.

SSM Health Care Guidelines

Treatment decisions for seriously ill and dying patients are often difficult for all those involved, especially patients and families. Many factors contribute to this difficulty, including, among others: lack of understanding among the patient and/or family about the seriousness of the patient's condition, ambivalence regarding just when to "let go," uncertainty as to when or what complication will eventually lead to the patient's death; inability of the patient to participate in decision making, lack of clarity about the patient's wishes, no designated proxy decision maker or durable power of attorney for health care; disagreement among family members, complex family dynamics and unresolved family issues; and poor or inconsistent communication among and by physicians and other caregivers, and divergent opinions and lack of coordination of care.

Given the difficulty of these decisions, physicians and other caregivers need to approach such situations with the utmost sensitivity and skill, recognizing that these are incredibly important and complex interventions. Though there is no single, established method for how best to do this, what follows are some simple guidelines with proven tools developed by physicians and other caregivers throughout SSM Health Care to help improve the way we deliver care to seriously ill patients. The guidelines are designed to: enhance communication with patients and families as well as among physicians and other caregivers; improve the coordination of patient care across disciplines and different settings; and prevent conflict situations from arising that can divide patients/families and physicians/other caregivers, compromise patient care, and lead to much moral distress. The emphasis of these guidelines is on dialogue, shared decision-making, coordination of care, and patients' best interests.

I. Guidelines for Communication and Care coordination

A. Communicate early and often with patients and families

Patients and families need to be informed early on about the patient's diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment options. They also need to be updated frequently about any new developments in the care and condition of the patient, such as progress, setbacks, effectiveness of current treatment modalities, alternate treatment options, and necessary changes in the goals of care. Too often patients and families are left in the dark, informed too late about the patient's true condition, and/or receive inconsistent information from the various physicians and other caregivers. As a result, they may form unrealistic expectations and misinterpret insignificant physical signs in the patient as genuine signs of improvement. Clear, consistent, and frequent communication with patients and families in language they can understand goes a long way in preventing this from happening.

B. Communicate early and often with other members of the care team

Related to this last point is the fact that physicians and other caregivers often do not communicate effectively or frequently among themselves. Not only can this lead to problems in the care of the patient but it can also be a significant source of confusion for patients and families as they are told different things by different caregivers. Physicians should be sure to talk often amongst themselves and with other caregivers about the patient's situation so they can better coordinate the patient's care. To avoid sending conflicting messages, it is often best to designate a single physician (e.g., the attending or primary treating physician) to communicate on a routine basis with the patient and family and, as appropriate, to relay the sentiments of the various caregivers back to them. This not only enables more effective and consistent communication but also lends itself to a more fruitful and trusting relationship with patients and families. For care conferences (see below), however, it is essential that most, if not all, of the physicians and other caregivers treating the patient are involved.

C. Determine the goals of care and evaluate routinely

Setting clear and realistic goals of care with patients and families and evaluating them frequently is critical for all patients, especially those who are seriously ill. Only when this is done can a care plan be developed that corresponds to the present reality of the patient's situation and her/his particular wishes and values. Additional benefits are that patients and families gain a better understanding of what can reasonably be hoped for through the care provided and physicians and other caregivers are able to come together in establishing a more holistic and coordinated care plan.

D. Make time for and participate in care conferences

One tried-and-true method for enhancing communication and coordinating care for seriously ill patients is to conduct a care conference early on in the patient's admission and as needed throughout the patient's stay. (See "From the Field" for a Facilitator Care Conference Check List and a Care Conference Record).

Care conferences allow the patient (if able), family members, physicians, and other caregivers to come together to discuss important issues, such as: reasonable treatment options; patient and family values, beliefs, and special needs; pain and symptom management; transition or discharge plans; code status; palliative and hospice care options; and so on. Unfortunately, care conferences are not a standardized, routine practice in medicine and are often only conducted when conflict has already manifested. The main reasons for this are that care conferences are seen by some as too time-consuming and it is difficult to get the various physicians and other caregivers all together at the same time. Health care facilities that do care conferences routinely, however, have found them to be very beneficial as time spent up front is often time and heartache saved in the end. Moreover, clinical data from recent studies indicate that care conferences are helpful in improving communication with patients and families as well as among caregivers, achieving consensus around reasonable goals of care, and avoiding intractable conflict. Palliative care physicians and nurses, case managers, social workers, among others, are typically well-trained to facilitate care conferences. Physicians should utilize their expertise. In some cases involving prolonged hospitalizations it may be necessary to have more than one care conference. Time should always be given to the patient and family to come to terms with what is discussed no matter how many care conferences are held.

E. Exercise care in offering/discussing treatment options

Too often patients and families are offered every treatment option possible and asked to decide what they want. Fortunately, this approach works most of the time as patients and families tend to make reasonable decisions after being given this inordinate amount of power. When the patient or family requests treatment that seems inappropriate or unreasonable, however, physicians object despite the fact they offered the option in the first place. Not only is this a poor practice in medicine founded upon the false claim that patients have absolute autonomy and physicians must honor any request no matter how impractical, but it also puts the patient and family in a difficult position as all the responsibility for treatment decisions shifts to them. A better practice, one built on the concept of shared decision making, is for physicians to offer only those treatment options that are reasonable and realistic in light of the patient's overall condition and the agreed-upon goals of care. With this comes the responsibility for physicians to engage in honest dialogue about why such treatment options might benefit the patient and why other possible options will not.

F. Address unreasonable requests up-front and candidly

Patients and families have a right to participate in treatment decisions and to make requests for treatment. However, physicians are not legally or ethically bound to carry out every request made by a patient or family. This is particularly true if the request for treatment will extend or increase the suffering of the patient without conferring a proportionate benefit, is medically contraindicated because the treatment will be ineffective, and/or violates generally accepted medical standards of care and is inconsistent with professional experience. Too often in the end of life context physicians acquiesce to unreasonable requests for treatment for fear of legal liability. Not only is this an abdication of physicians' responsibility to their patients, but it can also result in harm to the patient, moral distress in physicians and other caregivers, and the inappropriate use of limited health care resources. In addition to exercising care in offering treatment options, physicians need to address unreasonable requests up-front and candidly, accepting the responsibility that comes with their role as a medical professional and advocate for the patient.

G. Ensure non-abandonment and quality end of life care

As discussions are being held about treatment options for seriously ill patients, it is important for physicians to reinforce to patients and families that the patient will receive high-quality end of life care and not be abandoned if the decision is made to either withhold or withdraw treatment. Patients and families often think that once they decide against a more aggressive approach to treatment, the care of the patient will be compromised and they will be left on their own to attend to the needs of the patient. Unfortunately, this is sometimes the case in modern medicine and it is one reason why patients and families are inclined to press on with treatment against their better judgment. Physicians should be aware of the end of life care resources available to them, such as pain management experts, palliative care and hospice providers, chaplains, and bereavement support specialists. They should also call on these resources not only to assist them in caring for the patient but also as a sign that the patient will continue to receive appropriate care designed to promote comfort, dignity, and emotional/spiritual support. While it is important to enlist the help of others at this time, nothing can replace the presence and compassionate care of the attending or primary treating physician.

H. Once the decision has been made ...

If the decision has been made to withhold or withdraw treatment and it is likely that the patient will die rather soon while in the hospital or other health care setting, physicians and other caregivers should:

- Be sure everyone involved in the patient's care is aware of the decision

- Be appropriately present to the patient and family

- Attend to any requests of the patient and family that can be accommodated

- Address questions of organ and tissue donation as appropriate

- Discontinue monitors and alarms

- Cease any unnecessary treatments and assessments

- Move the machinery away from the bed

- Remove encumbering or disfiguring devices

- Have pain medications readily available so they can be provided as needed

- Attend to the psycho-social and spiritual needs of the patient and family

- Allow time and space for family and other loved ones to be present to the patient

- Prevent any unnecessary intrusions and noise in/around patient's room

II. Guidelines for Conflict Situations

Even if all the above guidelines are followed, some situations will arise when patients or families (typically families) will request "everything be done" when empirical evidence and the collective wisdom of physicians and other caregivers suggest the request is unreasonable. When this happens physicians need to have a candid, direct, and structured conversation with the family before the situation becomes unmanageable. What follows are some basic guidelines for having such a conversation, which can be conducted by the attending or primary treating physician alone or with a small team of caregivers that also includes the primary nurse caregiver, the case manager or social worker on record, a chaplain, and the palliative care and/or hospice specialist.

A. Establish the setting

The attending/primary treating physician should ensure comfort and privacy, sit down close to the family, and introduce the issue by saying something like: "I'd like to talk to you about the treatment you are requesting and the possible implications of this."

B. Determine level of understanding

The attending/primary treating physician should ask open-ended questions to find out what the family understands about the patient's diagnosis and prognosis. Consider asking this question: "What do you understand about your loved one's health situation?" The attending/primary treating physician and other team members should fill in any gaps in the family's level of understanding in clear and easy-to-comprehend terms and give them time to absorb any new information.

C. Clarify hopes and expectations

The attending/primary treating physician should talk to the family about the goals of care by asking questions like: "What do you think your loved one would want in this situation?" "What are your hopes and expectations if we provide the treatment you are requesting to your loved one?" If there is a sharp division between what is likely to happen and what the family hopes and expects to happen with regard to treatment, this is the time to express those concerns and clarify any misconceptions.

D. Discuss withholding or withdrawing treatment

The attending/primary treating physician should share with the family her/his thoughts about the lack of benefit regarding the treatment in question in language they can understand. This person should be firm, yet compassionate, in stating the reasons why she/he thinks the treatment would not promote the patient's overall best interests. Also, the attending/primary treating physician should point out the care options available to the patient (e.g., palliative and hospice care), and be sure to inform the family that withholding or withdrawing certain treatments does not mean abandoning appropriate care designed to promote comfort, dignity, and emotional/spiritual support. A palliative care consult should be initiated to further reinforce to the family that the patient will not be abandoned.

E. Respond to deeper needs

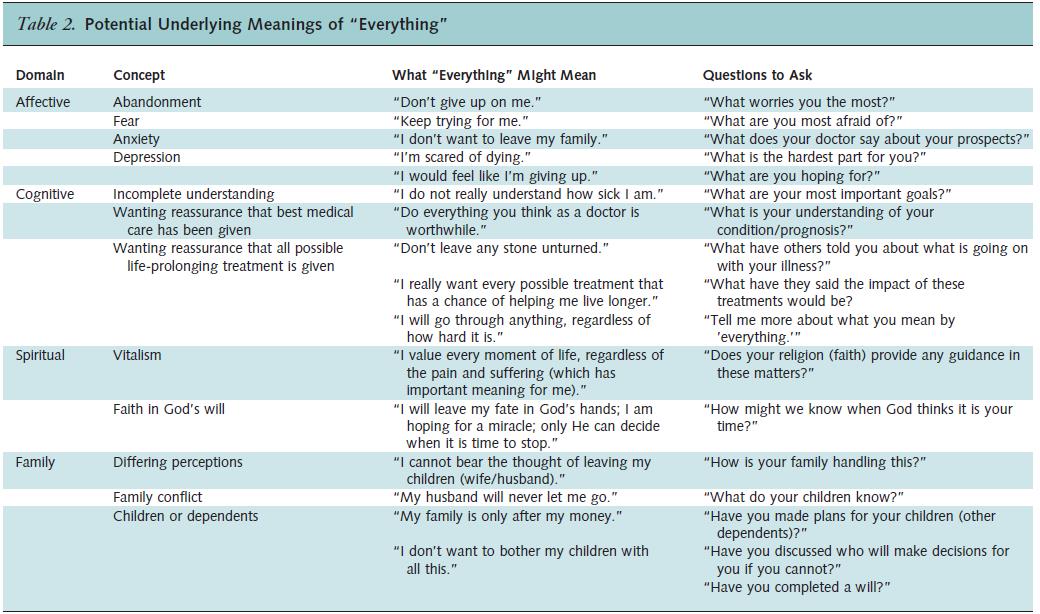

This is an extremely trying situation for the family, one that they are most likely facing for the first time. Beyond supplying important medical information, the attending/primary treating physician should also carefully listen to the family and try to determine the underlying reasons for the family's request to do everything. Often there is more than meets the eye and the attending/primary treating physician should seek help from pastoral care and/or social services to aid her or him in understanding and addressing the deeper motivations and needs of the family. For more information on understanding and responding to the underlying meanings of requests for "everything," (see Table below).14

F. Devise a care plan

If agreement has been reached with the family about withholding or withdrawing treatment, the attending/primary treating physician should establish a care plan that addresses all agreed-upon items and any other aspects of care that correspond to the patient's wishes, values, and beliefs and are necessary to maximize the patient's comfort. The attending/primary treating physician should maintain open lines of communication with the family throughout the dying process and continually update and comfort them. Also, if possible, the attending/primary treating physician should be present and company with the patient and the family as the patient approaches death.

G. Lack of agreement

If agreement cannot be reached about withholding or withdrawing treatment, an ethics consult should be called and the hospital president or administrator on-call should be notified of the situation. Additionally, attention should now focus on restricting treatment options in light of the patient's best interests with no treatment options being offered to the family that will extend or increase the patient's suffering (e.g., amputation of a limb for a patient with end-stage illness) or are medically contraindicated because they will be ineffective (e.g., advanced cardiac life-support for a frail, elderly patient with multiple chronic conditions).

G1. Offer time-limited trial

If the treatment in question does not extend or increase the patient's suffering and could perhaps achieve its physiological end, the attending/primary treating physician could offer the option of providing the treatment for a time-limited trial. The attending/primary treating physician must delineate the therapeutic goals and the length of time the treatment will be provided to assess the effects of the treatment in light of the goals. In no uncertain terms, the attending/primary treating physician should point out that the treatment will be withdrawn if the patient does not achieve the therapeutic goals in the designated time.

G2. Discuss alternate care options

If, after the time-limited trial, the treatment is still considered unreasonable or inappropriate, it could be withdrawn provided there is wide agreement among the attending/primary treating physician, other caregivers, hospital president, ethics committee, and so on. If the decision is made to withdraw the treatment, the family should be notified promptly and given an appropriate amount of time to reconcile with the situation or make alternative plans.

H. Documentation

It is imperative that all discussions and decisions made with family be thoroughly documented in the patient's chart (paper or electronic). This includes but is not limited to the following: the proceedings from any care conferences; structured discussions regarding the family's request for everything; any informal or formal ethics consultations; and decisions about offering time-limited trials with precise dates regarding when the treatment was started, what therapeutic goals were agreed upon to measure the patient's progress, and when the treatment will be withdrawn if the patient's condition does not improve when measured against the agreed-upon therapeutic goals.

I. Debrief with caregivers

Since these situations are often stressful and difficult for physicians and other caregivers, a formal debriefing meeting should be conducted during and after the stay of the patient so the physicians and other caregivers can express their feelings and be supported in their roles. This can be done through the particular unit, the ethics committee, or a special ad hoc meeting group.

Notes

- J. P. Burns and R. D. Truog, "Futility: A Concept in Evolution," Chest 132, no. 6 (December 2007):1987-93.

- D .J. Murphy and T. E. Finucane, "New Do-Not-Resuscitate Policies: A First Step in Cost Control," Archives of Internal Medicine, 153, no. 14 (July 26, 1993): 1641-48.

- L. J. Schneiderman, N. S. Jecker, and A. R. Jonsen, "Medical Futility: Its Meaning and Ethical Implications," Annals of Internal Medicine, 112, no.12 (June 15, 1990): 949-54.

- R. D. Truog, A.S. Brett, J. Frader, "The Problem with Futility," New England Journal of Medicine 326, no. 23 (June 4, 1992): 1560-64.

- A. Halevy and B. A. Brody, "A Multi-Institution Collaborative Policy on Medical Futility," Journal of the American Medical Association 276, no. 7 (August 21, 1996): 571-74.

- C. W. Plows, et al., "Medical Futility in End-of-Life Care — Report of the Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs," Journal of the American Medical Association 281, no. 10 (March 10, 1999): 937-41.

- R. L. Fine and T. W. Mayo, "Resolution of Futility by Due Process: Early Experience with Texas Advance Directives," Annals of Internal Medicine 138, no. 9 (May 6, 2003): 743-46. See also, M. L. Smith et al., "Texas Hospitals' Experience with the Texas Advance Directives Act," Critical Care Medicine 35, no. 5 (May 2007):1271-76.

- Ibid., 1991.

- Ibid., 1991-92.

- Ibid., 1992.

- T. E. Quill, R. Arnold, and A. Back, "Discussing Treatment Preferences with Patients Who Want 'Everything,'" Annals of Internal Medicine 151, no. 5 (September 1, 2009): 345-49.

- Ibid., 345-48.

- See, for example, A. Lautrette, MD; M. Ciroldi, MD; H. Ksibi, MD; É. Azoulay, MD, PhD. "End-of-Life Family Conferences: Rooted in the Evidence," Critical Care Medicine 34[Suppl.] (2006): S364-S372); R. D. Stapleton, MD, MSc; R. A. Engelberg, PhD; M. D. Wenrich, MPH; C. H. Goss, MD, MSc; J. R. Curtis, MD, MPH. "Clinician Statements and Family Satisfaction with Family Conferences in the Intensive Care Unit," Critical Care Medicine 34 (2006):1679-1685; R. D. Powazki, "The Family Conference in Oncology: Benefits for the Patient, Family, and Physician," Seminars in Oncology 38, no.3 (June 2011):407-12; I. H. Fineberg, M. Kawashima, S. Asch, "Communication with Families Facing Life-Threatening Illness: A Research-Based Model for Family Conferences," Journal of Palliative Medicine 14, no. 4 (April 2011): 421-7; E. Azoulay, "The End-of-Life Family Conference: Communication Empowers," American Journal of Respiratory & Critical Care Medicine 171, no. 8 (April 15, 2005): 803-4.

- Ibid.

Copyright © 2012 CHA. Permission granted to CHA-member organizations and Saint Louis University to copy and distribute for educational purposes. For reprint permission, contact Betty Crosby or call (314) 253-3490.