Mark Repenshek, Ph.D., Health Care Ethicist, Columbia St. Mary's Medical Center

Ethics consultation services in health care institutions are often dated to the mid-1970s in response to case law that involved difficult decisions concerning end-of-life care.1 Albert Jonsen points out that for a number of years prior, Catholic hospitals had already established "medico-moral" committees to deliberate over issues related to the then Catholic Hospital Association's Ethical and Religious Directives (ERDs).2 That long-standing tradition continues today in Catholic health care coupled with similar recommendations from regulatory agencies like the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations.3

For the Catholic health care ministry, the ERDs offer specific guidance:

An ethics committee or some alternate form of ethical consultation should be available to assist by advising on particular ethical situations, by offering educational opportunities and by review and recommending policies. To these ends, there should be appropriate standards for medical ethical consultation within a particular diocese that will respect the diocesan bishop's pastoral responsibilities as well as assist members of ethics committees to be familiar with Catholic medical ethics and, in particular, these Directives [emphasis added].4

This Directive suggests that every Catholic-sponsored health care ministry has a moral obligation to provide a form of ethical consultation attentive to standards that guide the consultation process. To that end, I will offer a descriptive piece on 196 ethics consultations at Columbia St. Mary's (CSM) from 2003 through 2007. In an attempt to address the matter of standards for the ethics consultation process, CSM's ethics committee chose to formulate a database beginning in 2003 to track trends in the ethics consultation process.5 This database now provides our ethics committees a resource from which to monitor trends in clinical issues that may arise, determine the impact of ethics consultation on patient care outcomes, and determine opportunities for proactive ethics education to diminish consultation as mere "dilemma resolution."

Since 2003, the CSM ethics consultation service has utilized the definition of ethics consultation provided by the American Society for Bioethics and the Humanities' Core Competencies for Health Care Ethics Consultation.6 CSM's ethics consultation service models its process as an ethics facilitation approach7 framed by the mission, vision and values of the health care ministry. At CSM, any member of the health care team with direct patient contact may request an ethics consultation, as may patients and family members/surrogate decision-makers.

Method

Of the ethics consultations performed between 2003 and 2007 at CSM, included in this study were those where the initial ethics committee member could identify an ethical dilemma; identify the person requesting the consultation; and offer recommendations where appropriate to the reason for request. Data were abstracted from completed ethics consultation intake forms, written analyses and recommendations, and patient medical records.

In addition to data captured from the patient's medical record, information was utilized from CSM's billing software (Invision). These data allowed access to the patient's Major Diagnostic Category (MDC) as well as discharge disposition. The MDC designation is obtained from the group code corresponding to the specific primary DRG for billing purposes for the patient in the hospitalization wherein ethics consultation was requested.8 The significant number of unknown MDC codes (see Table 1) is the result of inaccessible data within our billing software due to missing patient data at time of database construction. The category of discharge disposition is a locally constructed designation that is integrated into the ethics consultation database to better understand placement of the patient after the ethics consultation has occurred.

The HIPAA Waiver for this study was approved by the CSM Privacy Board in accordance with federal regulations. Data were compiled using Microsoft Access 2007 in collaboration with Harmony Technologies, LLC (Milwaukee Wisconsin).

Results

Columbia St. Mary's Health System is comprised of four acute care hospitals totaling roughly 650 beds. The system consists of an additional 33 clinics and employs roughly 180 physicians. In fiscal year 2008 our system had 342,182 outpatient visits, 69,346 Emergency Department visits and 25,891 inpatient admissions.

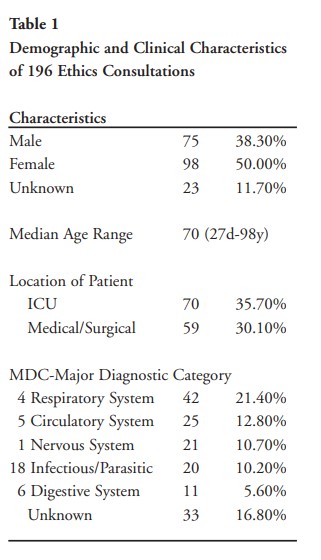

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study group are shown in Table 1. The median age for the 196 consultations was 70 (range: 27 days to 98 years). Of the 196 consultations 75 involved male patients (38.3%), 70 (35.7%) pertained to the intensive care units, and 59 (30.1%) in medical surgical units.

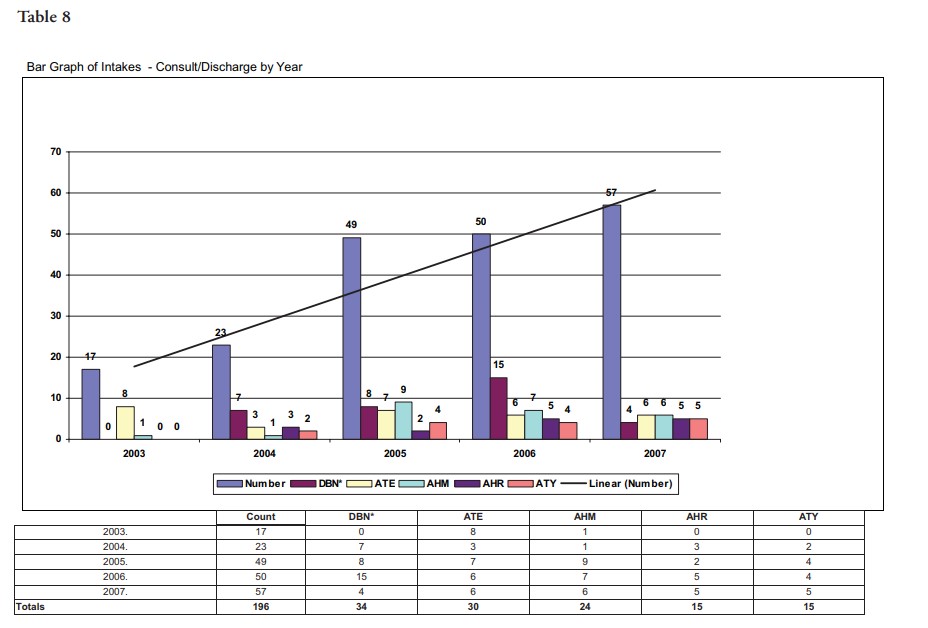

The consults involved a variety of diagnoses: diseases and disorders of the respiratory system (42 consultations, 21.4%), circulatory system (25 consultations, 12.8%), nervous system (21 consultations, 10.7%), and infectious disease (20 consultations, 10.2%). Of the 196 consultations, 48 (24.5%) involved patents who died while still in the hospital; however, other consultations involved patients who survived to hospital discharge (see Table 8).

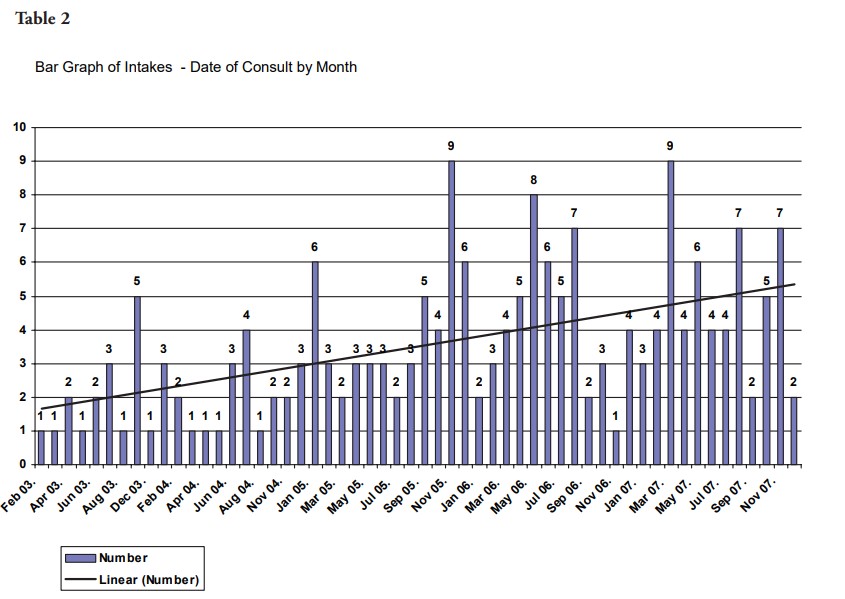

Ethics consultation steadily increased as a trend since 2003 with variances reflected in Table 2 on a month-by-month basis. This steady increase in ethics consultation continues despite inpatient discharges remaining relatively flat since 2003 (2004: 25,589 inpatient discharges; 2007: 25,776 inpatient discharges).

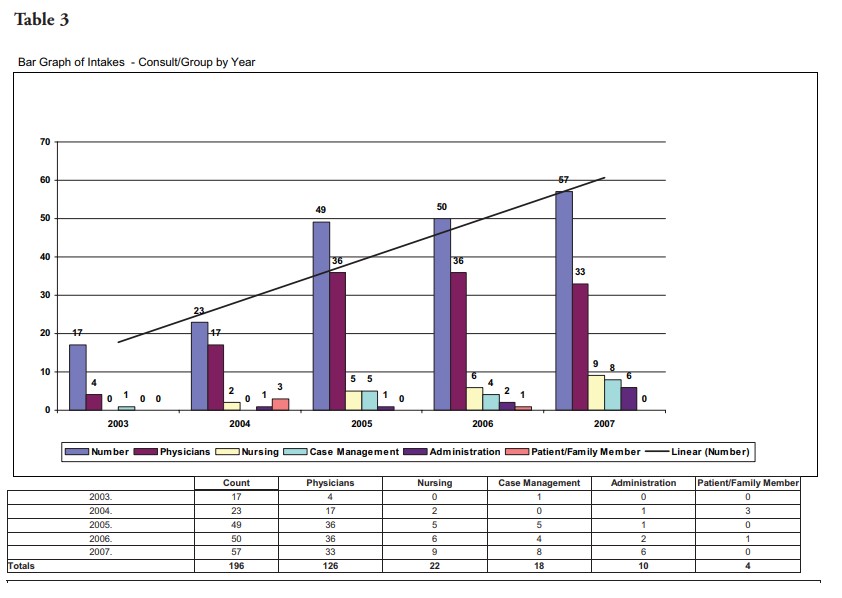

Ethics consultations were most commonly requested by physicians (64.3%; 126 of 196) (Table 3). Given that the CSM's ethics committees are medical staff committees, the data demonstrate a well-integrated consultation service into the medical staff. Of note for the CSM ethics committees, Table 3 demonstrates a relatively steady increase in the number of physician consultations with a slight decline as a percentage of total consults in 2007. A breakdown by specialty suggests that the top five consulting specialties are hospitalists (20.9%; 41 of 196), internal medicine (13.7%; 27 of 196), family medicine (10.7%; 21 of 196), followed by nursing (9.7%; 19 of 196) and case management (9.2%; 18 of 196) (see Table 4).

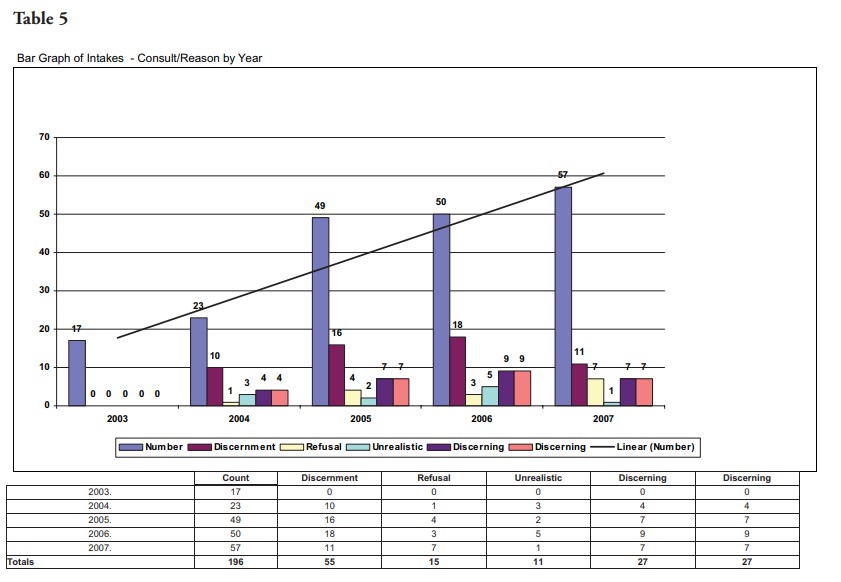

Most of the ethics consultations covered issues related to the discernment of patient's wishes/best interests (28.1%; 55 of 196). The next top four categories for ethics consultation request were (a) discerning evidence of patient's wishes (13.8%; 27 of 196); (b) discerning meaning of quality-of-life (13.8%; 27 of 196); (c) refusal of beneficial interventions (7.7%; 15 of 196; and (d) unrealistic expectations/understanding of benefit (5.6%; 11 of 196) (see Table 5).

Discussion

The ultimate concern of the ethics consultation database is quality improvement in ethics consultation. Those who call for ethics consultation within our hospitals deserve assurance that when they seek assistance from our ethics committees to sort through the ethical dimensions which their case presents, the ethics consultation service is competent and efficient in offering that assistance. Specific to Catholic health care, not only do the ERDs require "appropriate standards for medical ethical consultation," the communities we serve deserve demonstrable data in order to be transparent as to how the ethics consultation service maintains its standards for consultation.9

In 2005 CSM established standards for membership and related competencies for our ethics committees. Membership includes an interdisciplinary panel comprised of, but not limited to, physicians, medical directors of critical care settings, nursing, social work, chaplain services, palliative care, administration, dietary, respiratory therapy and community representation. Member expectations were established around attendance at meetings, confidentiality, knowledge of policy and procedures, and specific to this piece, standards for ethics consultation participation. To that end, all persons on the ethics committee must complete all four ethics education modules through the CSM Learning Institute.10 For those committee members who wish to participate in ethics consultation, an 80 percent pass rate must be achieved on all four modules and the participant must have attended at least two ethics consults in an observational role. Ultimate determination for serving as part of the ethics committee consultation ad hoc team is then made by the ethics committee chairperson and his/her designee and health care ethicist.

In order to measure quality improvement in ethics consultation our database was constructed to test four hypotheses. These hypotheses focus on a methodological critique of ethics consultation rather than a measure of satisfaction among consultants or requestor.11 The hypotheses were the following:

- As the level of ethics consultation is further integrated within the health care ministry, ethics consultation should occur closer to admission;

- Ethics consultation closer to admission will allow for consultation to be more advisory and directional than conflict resolution;

- As the level of ethics consultation is further integrated within the health care ministry and is advisory in nature, fewer consults will result in inpatient death as the discharge disposition; and

- Tracking trends in reason for consultation will allow for opportunities of organizational/clinical change in response to these trends.

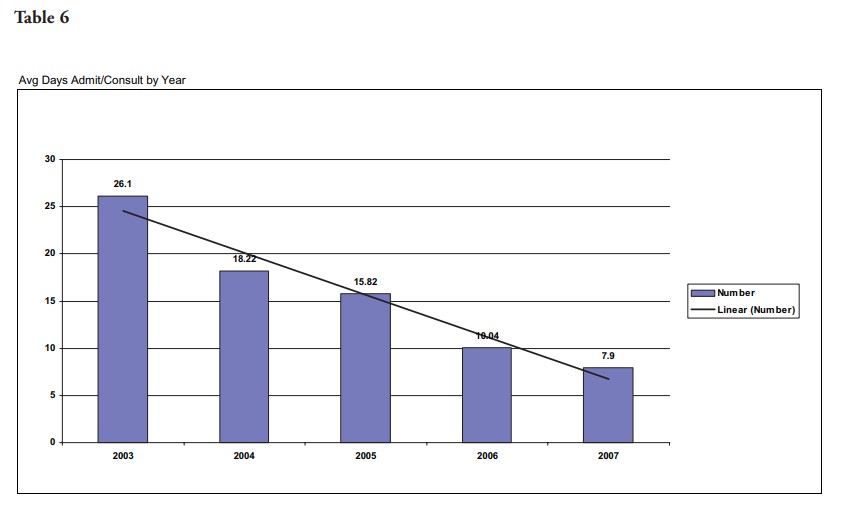

To the first hypothesis, Table 6 demonstrates the mean time elapsed from admission to date of ethics consultation for the patient aggregate to the year. The downward sloping line represents the declining trend of ethics consultation and its chronological proximity to the date of admission. At CSM, ethics consultation in 2003 occurred on average 26.1 days after admission of the patient compared with 7.9 days in 2007 (see Table 6, p. 12). The continuous trend downward in the proximity of time between consultation and admission suggests that while the number of consultations continues to increase (Table 2) the CSM ethics consultation service is being requested earlier in the patient's hospitalization.

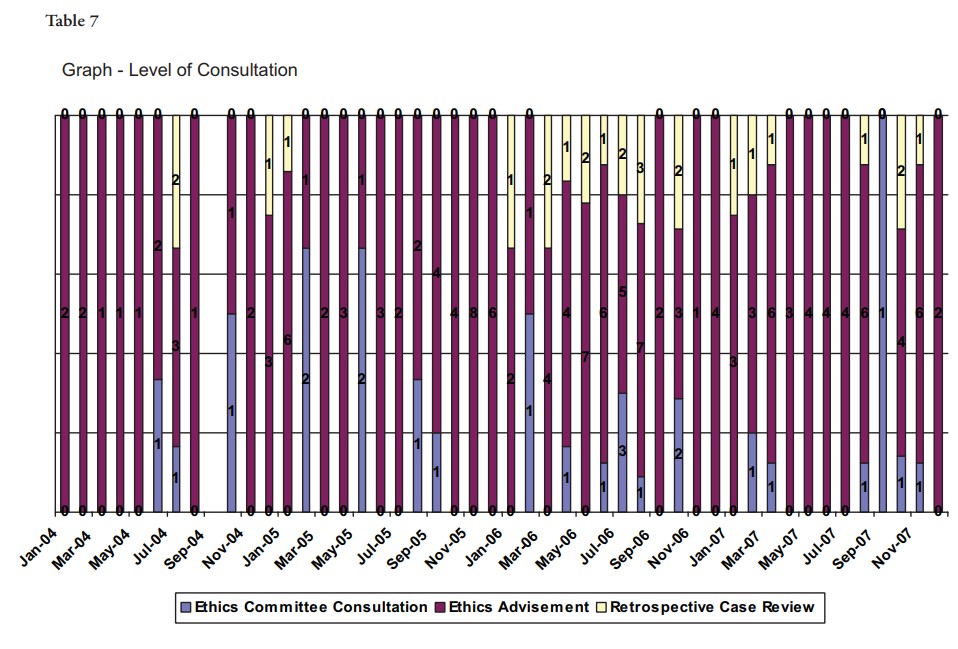

In 2004, CSM ethics committees began to differentiate between ethics consultation that was advisory in nature versus those that required ad hoc/full committee consultation. Ethics advisements are those consults that relate to interpretations of the ERDs or clarification of established CSM ethics policy and procedures. Advisement may also constitute a request to attend a family care conference wherein the opportunity arises to offer ERD or CSM ethics policy clarification. Ethics consultation is necessary for all ethical questions other than those advisory in nature. This distinction allowed us to measure the number of advisements versus consultation as these categories relate to the work of the ethics consultation service as well as monitor any trends therein. Ethics consultation constitutes 13.4% of total requests for ethics consultation (24 of 179; 2004-2007). Ethics advisement accounted for 84.9% of total requests for ethics consultation (152 of 179; 2004-2007). Of particular note is the increase in ethics advisement as a proportion of total consults by month from 2004-2007.12 Table 7 demonstrates the extent to which advisement compares to consultation as a proportion of total consults each month. Additionally, with increased awareness of ethics consultation and the services provided, retrospective case review continues to increase, most notably since 2006. Retrospective review is targeted education requested by a unit/department with the goal of organizational process change or development in response to the consultation requested. The overlay between these data (Table 7) and the trend data on the reason for consultation (Table 5) suggest that ethics consultation closer to admission has allowed for consultation to be more advisory and directional than conflict resolution. This conclusion is limited however, by an inability to make this claim with statistical significance.

In our series of 196 ethics consultations, 163 were identified by a discharge disposition. Of the 163 consults wherein the discharge disposition was identified, 48 consultations (29.4%; 48 of 163) involved patients who died while in the hospital, 31 consultations (19.0%; 31 of 163) were discharged to a home care hospice or hospice care in a hospital/medical facility, another 55 (33.7%; 55 of 163) were discharged to a Medicare-certified skilled nursing facility (SNF), a long-term care hospital or Medicare-certified SNF sub-acute facility. Table 8 trends the discharge disposition over time listing the five most frequent discharges compared against total consults per year. Since 2004, a discharge disposition of death in medical facility with no autopsy (DBN) comprised the most significant percentage of ethics consultations until 2007 in which there occurs a substantial decline. As a percentage of total consultations, Table 8 illustrates a decline in the discharge disposition designation of DBN from 30% of total ethics consultations to 7% (15 of 50 compared to that of 4 of 57). The overlay between the data on average time admission to consult (Table 6) and these trend data on discharge disposition may suggest that as ethics consultation continues to be requested closer to admission and more advisory in nature, that fewer patients receiving such consultation will be so acutely ill that death in the medical facility is a likely discharge outcome. Further substantiating this hypothesis, though less impressive statistically, it is important to point out that the trend data on the disposition to hospice in a hospital/medical facility also reveals a modest decline from 18.4% in 2005 (9 of

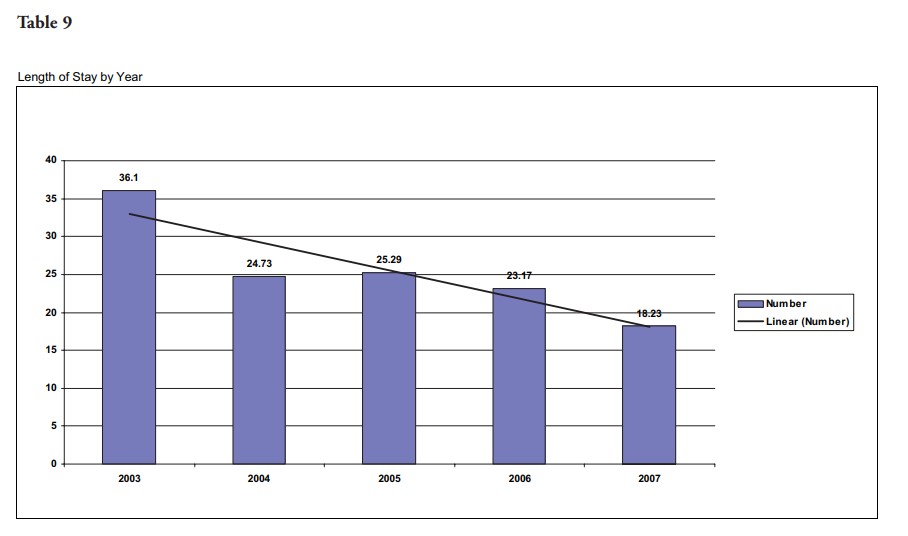

49) to 10.5% in 2007 (6 of 57). Less speculative is the impact ethics consultation has had on length of stay from 2003 to 2007. Since 2003, for those cases wherein ethics consultation was requested, the length of stay has been reduced in half from 36.1 days in 2003 to 18.23 days in 2007 (see Table 9).

As Swetz et al point out in their Mayo Clinic piece on 255 clinical ethics consultations at an academic medical center, "providing an opportunity for teaching and learning, the initial ethics consultation achieved resolution of most of the dilemmas (70% ) …" It is often the case that physicians, health care workers, patients and families would prefer to avoid the sometimes adversarial circumstances that can lead to ethics consultation. The focus on education, or advisement as we use that definition for the purposes of ethics consultation at CSM, can help to move ethics consultation away from conflict resolution to a integrated participant in good quality patient care. In many instances such a change in focus will require an organizational shift in the approach to ethics consultation.

The ethics database utilized by the ethics consultation service at CSM provides an opportunity to evidence the importance of that organizational shift with data — attending to hypothesis four. For example, the number of U.S. adults with completed advance directives is roughly 20% to 30%.13 To avoid ethical dilemmas and thereby the need for ethics consultation in response to conflict, some authors have suggested that advance care planning could help to discern patient goals and preference for their care in advance.14 In 2006, CSM adopted the model for advance care planning developed at the Gunderson Lutheran Health System. Implementation of this program at CSM resulted in a shift from data equal to the national average on advance care planning to that of 59% utilization on mortality review audit from 2006 through 2007 (n=527). In other words, 59% of the patients who died in our acute care hospital setting had an advance directive in place.15

Prior to implementation of Gunderson Lutheran Health System's program on advance care planning, a request for ethics consultation related to discernment of patient's wishes or discernment of evidence of patient's wishes comprised 46.9% of all consultations in 2005 (see Table 5). After two years of implementation of this advance care planning program, these same reasons for ethics consultation dropped to 31.5% of all consultations in 2007. Again, these data suggest that the increased utilization of advance care planning documents and the corresponding education necessary to facilitate organizational integration of the processes to respond to these documents have had a demonstrable impact on the request for clinical ethics consultation that was previously requested in the absence of such documents.

Stated more succinctly, these data demonstrate that the education and implementation necessary for an organizational shift in advance care planning can have a significantly positive impact on the reasons associated with ethics consultation.

I acknowledge limitations to this study. Although our database does compile 196 ethics consultations from 2003 to 2007, the work of the ethics committee members, related to advisement, may be underestimated by these numbers. The continual increase in consultation may also be more a result of the right committee membership on our ethics committees rather than an actual increase in the need for ethics consultation per se. Furthermore, the claims made with regard to correlating data between different metrix are not supported by a claim of statistical significance.

Conclusions

In 2007, Fox et al suggested that to ensure the quality and consistency of ethics consultation practice, there is a need for "clear standards for ethics consultation, for education resources … in implementing those standards, and for tools to evaluate whether the standards are being met."16 This target article in the American Journal of Bioethics, along with the corresponding response pieces, highlight the need for quality and consistency of ethics consultation practice. Currently the ASBH has appointed a task force to update the Core Competencies for ethics consultations headed by Anita Tarzian.17 In Catholic health care, this standard has been echoed in the ERDs either explicitly or implicitly since the Code of Medical Ethics for Catholic Hospitals, 1954 No. 8.18 Yet, in a 2006 article in Health Progress, Bernt and colleagues found that 86% of CHA-member hospital ethics committees believed that no prerequisites should be required for ethics committee membership and only 8% screen applicants. The respondent chairs of the ethics committees to the CHA survey revealed that 59% had a certificate program or less as background in medical ethics.19 In spite of these data, Bernt and colleagues did not call for attention to standards that guide the consultation process among CHA-member hospital ethics committees in their recommendations.20 This article serves as an entry point to offer data on 196 ethics consultation from 2003 to 2007 at a community-based Catholic hospital in order to begin to respond to our organizational ethical obligation to develop standards that guide the clinical consultation process.

NOTES

- In The Matter of Quinlan, 70 NJ 10, 355 A.2d 647 (1976), 668-669; Superintendent of Belchertown State School v. Saikewicz, 373 Mass. 728, 370 NE.2d 417 (1977); In re Colyer, 99 Wn.2d 114, 660 P.2d 738 (1983).

- Jonsen, A. The Birth of Bioethics. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998): 363.

- Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Comprehensive Accreditation Manual for Hospitals: The Official Handbook: CAMH. Oakbrook Terrace, IL; 2007, Standard RI 1.10; See also: Ellen Fox and Anita Tarzain, "Core Competencies for Ethics Consultations." Medical Ethics Advisor 24, no. 11 (2008): 127-128; Ellen Fox, et al. "Ethics Consultation in United States Hospitals: A National Survey." AJOB 7, no. 2 (2007): 13-25.

- USCCB. The Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Services. (Washington, DC: 2001), No. 37.

- Other analyses on clinical ethics consultation offer number similar or considerably lower numbers of consults and none are within a Catholic health care ministry, see: Swetz, KM et al. "Report of 255 Clinical Ethics Consultations and Review of the Literature." Mayo Clinic Proceedings 82 (2007): 686-691; Forde R and Vandvik IH. "Clinical ethics, information, and communication: review of 31 cases from a clinical ethics committee." J Med Ethics 31 (2005): 73-77; Waisel DB, et al. "Activities of an ethics consultation service in a tertiary military medical center." Mil Med 165 (2000): 528-532; Schenkenbert T. "Salt Lake City VA Medical Center's first 150 ethics committee case consultations: what we have learned (so far)." HEC Forum 9 (1997): 147-158.

- ASBH. Core Competencies for Health Care Ethics Consultation. (Glenview IL, 1998): 6-7

- The ethics facilitation approach is defined in the ASBH Core Competencies for Health Care Ethics Consultation, 1998.

- DRG Expert: A Comprehensive Guidebook to the DRG Classification System, 24th ed. (Ingenix, 2008).

- Fox and Tarzian, 128.

- These ethics education modules were developed largely by Ascension Health ethicists, John Paul Slosar, Ph.D. and Dan O'Brien, Ph.D. with minor input from an ethics advisory group within Ascension Health.

- For an example of ethics consultation services measuring outcomes of success in other contexts, see: Schneiderman, et al., "Effect of ethics consultations on non-beneficial life-sustaining treatments in the intensive care setting: A randomized controlled trial." JAMA 290 (2003): 1166- 1172.

- Please note the data starting in 2004 rather than 2003. This distinction was not created until 2004 as noted in the main text, hence first measurable in 2004.

- Susan Hickman, Bernard Hammes, Alvin Moss, and Susan Tolle. "Hope for the Future: Achieving the Original Intent of Advance Directives." Hastings Center Report 35 (2005): s26-s30; Research in Action, AHRQ, Issue #12, March 2003.

- Russ Kolarik, Robert Arnold, Gary Fischer, and James Tulsky. "Objectives for Advance Care Planning." Journal of Palliative Medicine 5 (2002): 697-704; Paul Dexter, Fredric Wolinsky, Gregory Gramelspacher, George Eckert, and William Tierney. "Opportunities for Advance Directives to Influence Acute Medical Care." Journal of Clinical Ethics 14 (2003): 173-182; Linda Emanuel, et al. "Advance Directives for Medical Care — A Case for Greater Use." 324 (1991): 889-895.

- Of note, at one of our inpatient sites (n=292) the advance directive utilization rate was 72% on in patient mortality review audit.

- Ellen Fox, et al. "Ethics Consultation in United States Hospitals: A National Survey." AJOB 7 (2007): 13-25

- Fox and Tarzian, 127.

- Gerald Kelly. Medico-Moral Problems (The Catholic Hospital Association; St. Louis, MO, 1958) 51-58. See also, John J. Mitchell. "New Challenges for Ethics Committees." Health Progress 81 (2000), viewed at http://www.chausa.org/pub/mainnav/news/hp/archive/ 2000/11novdec/articles/hp0011b.htm.

- Francis Bernt, Peter Clark, Josita Starrs and Patricia Talone. "Ethics Committees in Catholic Hospitals." Health Progress 87 (2006): 18-24.

- Bernt et al., 25

Copyright © 2009 CHA. Permission granted to CHA-member organizations and Saint Louis University to copy and distribute for educational purposes. For reprint permission, contact Betty Crosby or call (314) 253-3490.