Editor's Note: This analysis was prepared in July 2021 by Mary E. Homan, DrPH, MA, MSHCE, regional director of ethics for the Western Washington ministries of Providence St. Joseph Health, in collaboration with the Providence Ethics Leadership Council. We are pleased to share the statement with HCEUSA readers to promote awareness and support for the statement among ethicists, leaders of Catholic health care and those interested in advocating for just global distribution of COVID-19 vaccines.1

Introduction

As the world enters a second year of the global health crisis that is COVID-19, a variety of ethical, regulatory, and political questions have surfaced. Many of these inquiries, such as "What is fair?" or "What is right?" continue to confound health care professionals, operational leaders, and ethicists. What may have seemed right or fair in April of 2020 can no longer be viewed as such when we reexamine systemic discrimination, inequity, and scarcity.

As we focus our attention on the distribution of vaccines to prevent transmission of COVID-19, communities remain hindered by disparities and disenfranchisement, thwarted in attempts to procure let alone dispense the vaccine due to infrastructure and delivery issues. Often the benefit of the many, sometimes at the detriment of the few, continues to dominate public health planning and implementation during this pandemic. Countries with greater wealth and health care resources continue to tame the disease but poorer countries, historically beleaguered by sanctions, poverty, and 'otherness' fail to find rescue in the vaccine. This shared statement from Catholic health care ethicists intends to serve as a prophetic call to action, to employ institutional conscience, and to transcend national boundaries to foster collaboration among global partners, both religious and secular, to reach those in desperate need of life-saving vaccines.

Background

Background

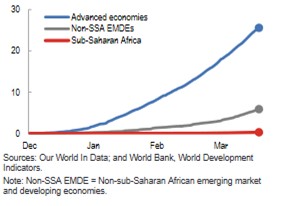

While the United States moves towards 50% of the total population vaccinated, countries in Sub-Saharan Africa contend with less than 1% of the total population vaccinated.2 In the US, front-line caregivers, eligible adults and young adults, and vulnerable persons continue to decline vaccines for a variety of reasons whereas in Africa even essential workers have yet to be provided vaccine access.3 Vaccine nationalism, "the act of reserving millions of doses of new vaccines for domestic use during a transnational public health crisis,"4 is not a new concept. Contractual relationships pre-production help ensure production continues and that targeted recipients are available once the vaccine reaches market. However, the KFF found that "although high-income countries only account for 19% of the global adult population, collectively, they have purchased more than half (54%, or 4.6 billion) of global vaccine doses."5

Figure 1. Selected Regions: Vaccine Doses Administered (per 100), 2021. Source: IMF

It seems difficult, however, to justify the excess amount of vaccine to the United States as individuals not only decline vaccine but also close to 190,000 doses of these precious resources have been wasted. According the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), close to 71% of vaccine waste derives from well-regarded pharmacy chains.6 Additionally, recent CDC guidance recommends that providers "should not miss any opportunities to vaccinate every eligible person who presents at a vaccination site, even if it means puncturing a multidose vial to administer vaccine without having enough people available to receive each dose."7 The rationale is clearly stated: the more persons who get vaccinated, the fewer hospitalizations and deaths. However, how must this 'waste' appear to countries who have been allocated so few doses?

One area of concern remains with the question of who will subsidize a global production schedule, as most of the vaccines pledged have been produced in countries which are redistributing their manufactured products to low- and middle-income countries. Inadequate access to raw materials, regulatory hold-up, vaccine-manufacturing capacity (including patent protections), and the use of multiple supply chains hinder manufacture and distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine.8 These barriers exacerbate the disparity pathway which includes "pre-existing disease burden and baseline susceptibility, limited disease prevention resources, and unequal access to basic and specialized health care, essential drugs, and clinical trials."9

Some amount of promise peeks through with the May 21, 2021 announcement that Pfizer and BioNTech pledged 1 billion doses of the COVID-19 vaccine with another 200 million pledged from Johnson & Johnson and 100 million pledged by Moderna, all at cost for low-income countries and at a low profit for middle-income countries.10 The COVAX program, a joint initiative supported by global philanthropic partner CEPI, the global vaccine alliance Gavi, as well as the World Health Association (WHO) and UNICEF, has promised equitable access to the COVID-19 vaccine for those countries. The President of the United States has committed $4 billion to support COVAX and to share, by the end of June, 80 million doses of the US vaccine supply.11

One would hope, then, that those global organizations will acquire the vaccine doses and work to create a robust delivery network to assure a fair distribution of the vaccine. However, as the recent CHA publication Renewing Relationship: Essays as We Evolve and Emerge from Pandemic suggests, the fragile health care infrastructures or inappropriate technologies12 of low- and middle-incomes countries struggle with service delivery. Unfortunately, even if COVAX were to distribute all 1.12 billion doses to low- and middle-income countries, less than half of the adult populations in those countries would be able to be vaccinated.13 In his encyclical Fratelli tutti, Pope Francis gently reprimands that "[a]side from the different ways that various countries responded to the crisis, their inability to work together became quite evident. For all our hyper-connectivity, we witnessed a fragmentation that made it more difficult to resolve problems that affect us all."14 Cardinal Turkson all but shouts that the pandemic "should be a wake-up call for countries to finally walk the talk about strengthening health care systems and making services accessible!"15

A tangential issue to vaccine allocation includes the type of vaccine made available to low- and middle-income countries. Concerns have arisen about both the logistics issues associated with certain vaccines, e.g. requiring extreme refrigeration, spoilage of the dose after opening a vial, as well as two-shot regimes versus one-shot doses and the efficacy of each type. Haiti, for example, rejected the vaccine proposed by WHO and requested that it be replaced "with another vaccine more suitable for Haiti."16 While Haiti has largely been spared from COVID-19, and has one of the lowest death rates in the world, officials are concerned that a deadly surge, similar to India, may be coming.17 Without the vaccine that fits their particular situation, however, will persons be able to protect themselves against the disease?

A Call to Action

Those who serve in Catholic health care have struggled against a strict utilitarian approach that has dominated public health and health care planning during the pandemic, especially when questions remain unanswered for persons who are disenfranchised. Lysaught and McCarthy opine that "those who work in Catholic health care feel compelled not only to participate in global health ventures; they often feel deeply moved to act by humanitarian disasters."18 A Shared Statement of Identity for the Catholic Health Ministry begins with the reminder that the people of Catholic health care serve a ministry which continues Jesus' mission of love and healing while working to bring alive the Gospel vision of justice and peace.19 We must continue to profess the importance of human flourishing, care for the whole person, solidarity, subsidiarity, justice, and promotion of the common good well beyond the immediate disaster of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In order to live into our shared calling, we must do more than simply opine or support in-word-only that a just global distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine is necessary. We must call upon the physical, financial, and operational skills of our organizations and we must do so in two parts: 1. Attend to the immediate needs of those in lower- and middle-income countries and 2. Plan for mitigating future disparities in care such as through a redistribution of resources. Three values guide the recommendations that follow: solidarity, justice, and the common good.

Solidarity

Recognizing and cherishing each person as created in the image and likeness of God requires we stand in communion with our fellow humans by attending to both the immediate and chronic needs of persons experiencing disenfranchisement or disparity. Pope Francis suggests that solidarity "presumes the creation of a new mindset which thinks in terms of community and the priority of the life of all over the appropriation of goods by a few."20 Decisions must be made out of a sense of both solidarity and with subsidiarity, especially insisting that those who are closer to the problems and closer to the ground can efficiently and effectively handle those functions so that all actively participate and cooperate.21

Justice

"Justice is essentially relational, and it includes at once both a recognition of the individual's dignity and an acknowledgment of the rights and responsibilities of individuals and society."22 Richard McBrien reminds us that "[w]e are not the ultimate source of the goods we have, but rather the stewards of what has been given to all of us by a gracious God."23 To act on behalf of justice requires particular concern for the historically and chronically marginalized and a bold step towards giving not of our excess but of our store and turning efforts towards helping those for whom justice has been absent.

Common Good

The common good, those "social conditions that allow people to reach their full human potential and to realize their human dignity"24 obliges both individuals and groups to contribute to the common welfare of all.25 Pope Francis challenges us to recall that "one person's problems are the problems of all. Once more we realized that no one is saved alone; we can only be saved together."26 Blessed Dorothy Day recounts Peter Maurin's words that "we must have a sense of personal responsibility to take care of our own, and our neighbor, at a personal sacrifice.'"27

Analysis and Recommendations

Attending to the Immediate Needs of Vaccine Distribution Worldwide

As we have seen in our own struggles in the United States to store, transport, and distribute vaccine, refrigeration requirements and the lack of a well-funded public health infrastructure caused delays in administering vaccines. Similar struggles threaten vaccine distribution in communities lacking adequate health services or outside groups are hindered from coming in to deliver health care. While the disease itself is borderless, interventions to curb the disease, including vaccine distribution, lockdowns, and separating the healthy from the ill, occur within bordered lands28 and action plans29 or recommendations often rely on political alliances of high-income countries.

Perhaps a more novel, and subtle, approach such as empowering, funding, and supplying Catholic churches and parish nurses with the resources necessary to serve as the trusted community vaccinator. Catholic health systems, channeling the spirit of the founding sisters,30 possess wide expertise and a deep history of training nurses, physicians, and community health workers and other health professionals to build capacity both locally31 and globally,32 especially in resource-challenged areas and could be trusted to train the health care workers needed to distribute the vaccine.

Leveraging partnerships with supply chain vendors, non-governmental organizations, and other global health partners are well within the scope and expertise of operational leaders in Catholic health care to purchase and provide gloves, needles, and the other supplies necessary for successful vaccination sites as well as provide financial assistance to such efforts. Such is the recommendation from Vatican COVID-19 Commission and the Pontifical Academy for Life which speaks of a "global cure with 'local flavour' [sic]."33 Catholic health systems are uniquely positioned to advocate for policy changes both locally (state and federal) and globally to enable redistribution of vaccine doses already purchased by high-income countries to be sent to low- and middle-income countries.

Planning for Future Distribution of Resources and Mitigating Disparities in Care

Sometimes global health efforts receive criticism that an organization directs time, talent, and resources towards international partners and communities when there are unaddressed or even blatantly ignored disparities in local neighborhoods, especially those that surround the health facility. Pope Francis meets this concern head on in his apostolic exhortation Evangelii gaudium "An innate tension also exists between globalization and localization. We need to pay attention to the global so as to avoid narrowness and banality. Yet we also need to look to the local, which keeps our feet on the ground. Together, the two prevent us from falling into one of two extremes."34

We are beholden to our local and global communities both in the immediate and in the future. Just as many of the founding religious sisters initially came to the United States "for the long-term with a vision of working to create long-term effects … They thought carefully about how they were going to develop structures and infrastructure to care for those in need."35 To avoid a lens of imperialism or toxic charity, we must embrace and operationalize the six Guiding Principles for Conducting Global Health Activities.36 Catholic health care should support existing infrastructure which works without attempting to re-create delivery systems which are neither desired nor supported by local community members; such guidance serves both global health initiatives and local health initiatives as well.

Reducing the burden of disparities both globally and locally signifies a deep commitment to the healing mission of Jesus. When vaccines first became available, some front-line caregivers and essential workers felt guilty they were taking a vaccine from another who may have needed it more,37 especially for persons who have experienced historic, chronic, and systemic discrimination or disparity. A redistribution of resources includes not only distributing the COVID-19 vaccines to resource-poor areas but a close examination of how our economic activity of health care practices in the United States, including the sourcing of materials, have moral implications and consequences as Pope Benedict reminds us in his encyclical Caritas in veritate.38

By leveraging existing partnerships, continuing the important work of short-term medical mission trips and assistance during disaster, and committing to future equitable distribution of resources, Catholic health care can be seen as universal as the Church herself.

Mary E. Homan, DrPH, MA, MSHCE

Regional Director of Ethics

Providence

Peter J. Cataldo, PhD

Senior Vice President, Theology and Ethics

Providence

Nicholas Kockler, PhD, MS, HEC-C

Vice President, System Ethics Services

Providence

Karen Pavic-Zabinski, PhD, RN, MSN, MBA, MA, MS

Regional Director of Ethics

Providence

Anita Ho, PhD, MPH

Regional Director of Ethics

Providence

Mark F. Carr, MDiv, PhD

Regional Director of Ethics

Providence

Kevin M. Dirksen, M.Div., M.Sc., HEC-C

Andy & Bev Honzel Endowed Chair in Applied Health Care Ethics

Regional Director of Ethics

Providence Center for Health Care Ethics

Jennifer Dunatov, DHCE

Clinical Ethicist

Providence

Doyle D. Patterson, PhD, BCC

Clinical Ethicist

Providence

Ken Homan, PhD

Vice President of Health Care Ethics and Theology

SCL Health

Michael McCarthy, PhD

Associate Professor

Neiswanger Institute for Bioethics and Healthcare Leadership

Loyola University Chicago

Jason T. Eberl, PhD

Professor of Health Care Ethics and Philosophy

Director, Albert Gnaegi Center for Health Care Ethics

Saint Louis University

Kelly Stuart, MD, MPH, MTS, MSNDR

Vice President, Ethics

Bon Secours Mercy Health

Steven Squires, PhD, MA, MEd

Vice President, Ethics

CHRISTUS Health

M. Therese Lysaught, PhD

Professor

Neiswanger Institute for Bioethics and Health Policy, Stritch School of Medicine

Loyola University Chicago

Pontifical Academy for Life, Corresponding Member

G. Kevin Donovan, MD, MA

Pellegrino Center for Clinical Bioethics

Professor, Georgetown University Medical Center

Daniel P. Sulmasy, MD, PhD, MACP

André Hellegers Professor of Biomedical Ethics

Director

Kennedy Institute of Ethics

Georgetown University

Peter A. Clark, SJ, PhD

John McShain Chair in Ethics

Professor of Medical Ethics

Director-Institute of Clinical Bioethics

Saint Joseph's University

Rev. Myles N. Sheehan, SJ, MD

Director, Pellegrino Center for Clinical Bioethics

Professor of Medicine

David Lauler Chair in Catholic Health Care Ethics

Georgetown University Medical Center

Margaret Somerville, AM, FRSC, DCL

Professor of Bioethics, School of Medicine University of Notre Dame Australia, Sydney.

Emerita Samuel Gale Professor of Law, Emerita Professor Faculty of Medicine, Emerita Founding Director Centre for Medicine, Ethics and Law, McGill University Montreal, Canada

ENDNOTES

- Mary E. Homan, DrPH, MA, MSHCE, Regional Director of Ethics, Western Washington, Providence prepared this analysis in collaboration with the Providence Ethics Leadership Council.

- Josh Holder, "Tracking Coronavirus Vaccinations around the World," The New York Times, n.d., sec. World, accessed May 21, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/world/covid-vaccinations-tracker.html.

- International Monetary Fund, Regional Economic Outlook. Sub-Saharan Africa: Navigating a Long Pandemic (Washington, D.C: International Monetary Fund, April 2021), 1, https://www.imf.org/-/media/Files/Publications/REO/AFR/2021/April/English/text.ashx.

- Ana Santos Rutschman, "Is There a Cure for Vaccine Nationalism?," Current History 120, no. 822 (January 1, 2021): 9.

- Anna Rouw et al., "Global COVID-19 Vaccine Access: A Snapshot of Inequality," KFF, March 17, 2021, accessed June 30, 2021, https://www.kff.org/policy-watch/global-covid-19-vaccine-access-snapshot-of-inequality/.

- Joshua Eaton and Rachana Pradhan, "CVS and Walgreens Have Wasted More Vaccine Doses than Most States Combined," Kaiser Health News, May 3, 2021, accessed May 23, 2021, https://khn.org/news/article/cvs-and-walgreens-have-wasted-more-vaccine-doses-than-most-states-combined/.

- CDC Vaccine Task Force, Distribution and Pharmacy, Identification, Disposal, and Reporting of COVID-19 Vaccine Wastage (Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, May 18, 2021), https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/downloads/wastage-operational-summary.pdf.

- Prashant Yadav and Rebecca Weintraub, "4 Strategies to Boost the Global Supply of COVID-19 Vaccines," Harvard Business Review, May 6, 2021, accessed June 11, 2021, https://hbr.org/2021/05/4-strategies-to-boost-the-global-supply-of-covid-19-vaccines.

- Anita Ho and Iulia Dascalu, "Relational Solidarity and COVID-19: An Ethical Approach to Disrupt the Global Health Disparity Pathway," Global Bioethics 32, no. 1 (January 1, 2021): 35.

- Associated Press, "Vaccine Makers Pledge 2.3B Doses to Less Wealthy Nations," Washington Post, May 21, 2021, sec. Business, accessed May 23, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/pfizer-biontech-pledge-2b-doses-to-less-wealthy-nations/2021/05/21/b2621564-ba47-11eb-bc4a-62849cf6cca9_story.html.

- Statement by President Joe Biden on Global Vaccine Distribution, Briefing Room Statement (Washington, D.C.: The White House, June 3, 2021), accessed June 11, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/06/03/statement-by-president-joe-biden-on-global-vaccine-distribution/.

- M. Therese Lysaught, "Vatican: It's Unjust (and Dangerous) for Wealthy Nations to Hoard the COVID Vaccine," America Magazine, January 27, 2021, accessed May 24, 2021, https://www.americamagazine.org/politics-society/2021/01/27/covid-vaccine-distribution-united-states-vatican-239797.

- Rouw et al., "Global Covid-19 Vaccine Access."

- Pope Francis, Fratelli Tutti Papal Encyclical, 7 (Assisi 2020).

- Peter Cardinal Kodwo Appiah Turkson, "COVID-19 and the Future of Global Health: Challenges and Opportunities," in Renewing Relationship: Essays as We Evolve and Emerge from Pandemic (The Catholic Health Association of the United States, 2020), 13.

- Onz Chéry, "Official Confirms Haiti Rejected COVID Vaccine, Asked for Another," The Haitian Times, last modified April 12, 2021, accessed May 26, 2021, https://haitiantimes.com/2021/04/12/official-confirms-haiti-rejected-covid-vaccine-asked-for-another/.

- Jason Beaubien, "One of the World's Poorest Countries Has One of the World's Lowest COVID Death Rates," Morning Edition, National Public Radio (National Public Radio: National Public Radio, May 4, 2021), accessed May 26, 2021, https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2021/05/04/992544022/one-of-the-worlds-poorest-countries-has-one-of-the-worlds-lowest-covid-death-rat.

- M. Therese Lysaught and Michael P. McCarthy, "Part Five: Embodying Global Solidarity," in Catholic Bioethics and Social Justice: The Praxis of US Health Care in a Globalized World, ed. M. Therese Lysaught and Michael P. McCarthy (Collegeville, Minnesota: Liturgical Press Academic, 2018), 299.

- The Catholic Health Association of the United States, "A Shared Statement of Identity for the Catholic Health Ministry," n.d., https://www.chausa.org/mission/a-shared-statement-of-identity.

- Pope Francis, Evangelii Gaudium Apostolic Exhortation, 188 (Saint Peter's, Rome 2013).

- Benedict M. Ashley, Jean DeBlois, and Kevin D O'Rourke, Health Care Ethics: A Catholic Theological Analysis, 5th Edition. (Washington, D.C: Georgetown University Press, 2006), 47; William J. Byron, "Ten Building Blocks of Catholic Social Teaching," America 179, no. 13 (October 31, 1998): 9 – 12.

- Kevin D O'Rourke and Philip Boyle, Medical Ethics: Sources of Catholic Teachings (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2011), 22.

- Richard P McBrien, Catholicism, vol. Two (Minneapolis, Minn.: Winston Press, 1980), 1048.

- Byron, "Ten Building Blocks of Catholic Social Teaching," 10.

- Pope John XXIII, Pacem in Terris Papal Encyclical, 53 (St. Peter's, Rome 1963).

- Pope Francis, Fratelli Tutti, no. 32.

- Dorothy Day, The Long Loneliness: The Autobiography of Dorothy Day (San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1980), 179.

- Christian Wille and Florian Weber, "Analysing Border Geographies in Times of COVID-19," in Self and Society in the Corona Crisis. Perspectives from the Humanities and Social Sciences, ed. Georg Mein and Johannes Pause, The Ends of Humanities, Band 2 (University of Luxembourg: Melusina Press, 2020), accessed June 29, 2021, https://www.melusinapress.lu/projects/self-and-society-in-the-corona-crisis.

- Center for Global Development et al., "Open Letter to G7 Leaders: A G7 Action Plan to Ensure the World Is Vaccinated Quickly and Equitably," June 7, 2021, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5f85f5a156091e113f96e4d3/t/60be19c38047482c54ffb913/1623071174389/G7+letter_Final_FOR+RELEASE.pdf.

- M. Ursula Stepsis and Dolores Ann Liptak, eds., Pioneer Healers: The History of Women Religious in American Health Care (New York: Crossroad, 1989).

- Barbra Mann Wall, Unlikely Entrepreneurs: Catholic Sisters and the Hospital Marketplace, 1865-1925, Women, gender, and health (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2005).

- Bruce Compton, "Creating Partnerships to Strengthen Global Health Systems," in Catholic Bioethics and Social Justice: The Praxis of US Health Care in a Globalized World, ed. M. Therese Lysaught and Michael P. McCarthy (Collegeville, Minnesota: Liturgical Press Academic, 2018), 325 – 7.

- Vatican Covid-19 Commission and Pontifical Academy for Life, "Vaccine for All. 20 Points for a Fairer and Healthier World," December 29, 2020, no. 16, https://press.vatican.va/content/salastampa/en/bollettino/pubblico/2020/12/29/201229c.html.

- Pope Francis, Evangelii Gaudium, no. 234.

- Compton, "Creating Partnerships to Strengthen Global Health Systems," 317.

- The Catholic Health Association of the United States, Guiding Principles for Conducting Global Health Activities, 5th Anniversary Edition. (Saint Louis/Washington, DC: The Catholic Health Association of the United States, 2020), chausa.org/guidingprinciples.

- Elizabeth Lanphier, "Vaccine Guilt Is Good — as Long It Doesn't Stop You from Getting a Shot," The Conversation, n.d., accessed June 11, 2021, http://theconversation.com/vaccine-guilt-is-good-as-long-it-doesnt-stop-you-from-getting-a-shot-158353.

- Pope Benedict XVI, "Caritas in Veritate" (Papal Encyclical, Saint Peter's, Rome, June 29, 2009), no. 37, http://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_ben-xvi_enc_20090629_caritas-in-veritate.html.