Michael Panicola, Ph.D., Corporate Vice President, Ethics, SSM Health Care

Catholic health care (CHC) is acutely aware, and has been for some time, that its mission-bearers are changing. With the number of active religious sisters decreasing, lay leaders are increasingly assuming primary responsibility for carrying on the mission of Catholic health care (CHC) and of the Catholic health care organizations (CHCOs) to which they belong.

This transition, as we well know, is not without its challenges. In large part, they are due to the fact that lay leaders are different from religious sisters in a number of ways. There is a difference in training, commitment, time, focus, and, to some extent, values and vision. Generally speaking, lay leaders do not go through extensive and ongoing formation for their work in the ministry, do not commit the whole of their lives to the ministry because of their various other commitments, cannot focus solely or primarily on their work given their responsibilities to others, and are not able to rely on a community to support them financially and help meet their other more basic needs.

Yet every day, at all levels, these lay leaders are faced with value-laden decisions related to mission, and are challenged to preserve the identity and integrity of the Catholic health care ministry in an environment that is highly complex, competitive and market-driven.

Ensuring Identity and Integrity

Catholic health care organizations have done much over the years to help ensure the identity and integrity of the ministry and to strengthen the mission and values of the organization. These strategies include:

- Policies and procedures that are reflective of the mission and values

- Decision making processes that help employees systematically think through issues in light of the mission and values

- Hiring practices that bring the most talented individuals committed to the mission and values into the organization1

- Ongoing formation programs for leadership that inculcate the mission and values and cultivate ethical sensitivity for decision making, and

- Evaluative mechanisms for ensuring integrity (e.g., identity assessment or measurement tools, performance evaluations that incorporate ethical standards of behavior derived from the values, bonus/incentive plans reflective of the mission and values and not just financial goals).

These and other strategies have gone a long way in our ongoing attempts to ensure the mission and values of Catholic health care and of Catholic health care organizations. However, there is at least one area that may need considerably more attention.

Time and again, it seems that lay leaders do not understand sufficiently what the values mean and how they ought to shape their everyday decisions and actions. Perhaps we need to be more explicit and intentional in helping lay leaders understand the dynamic meaning of our values so they can use them to guide their actions in complex, changing circumstances. It is not sufficient to simply articulate or espouse a list of values and expect that they will somehow be "operationalized" in everyday decision making. Such an approach could lead to a gap between who we claim to be (identity) and how we act (integrity).

If we have learned anything in recent years from the likes of Enron, Arthur Andersen, AIG and various other corporate scandals, it is that nothing is more insidiously destructive to an organization and the morale and well-being of its employees than a disconnect between who an organization claims to be and how it acts. We ought not forget that Enron had some of the very same organizational values as many of our CHCOs (communication, respect, integrity, and excellence), yet utterly failed. Why is this? What was it in Enron's culture, for example, that allowed the values of the organization to be so blatantly compromised?

In part, it had to do with the fact that Enron's values never truly permeated the mindset of its leaders or the culture of the organization. This is one of the dangers if we fail to provide meaning and add content to our values so that they can be used not only to drive action but also to measure accountability. If an organization says its stands for certain values like respect, integrity, and so on, there should be some specific and objective content behind those values that provides a backdrop for evaluating the actions of those who act on the organization's behalf.

In light of this challenge, the remainder of this article seeks to provide some depth to the core values of CHC and show how we can use these values in decision making to pursue our mission more effectively and, thereby, avoid the identity/integrity gap. This is not merely an academic exercise. This issue has come out of discussions with senior leaders, middle managers, physicians, nurses, and other lay leaders who have expressed concerns about their ability to live out the mission of CHC in the current environment. What follows has been shaped by and tested with hundreds of such lay leaders, most of whom appreciated the opportunity to learn more about what lies behind the core values of CHC and felt that their increased knowledge of the values better positioned them as leaders to make values-based decisions reflective of the mission.

Values of Catholic Health Care

What are the core values of CHC? A helpful list with which most would agree is found in the Shared Statement of Identity for the Catholic Health Ministry by the Catholic Health Association of the United States.2 The statement outlines several values (called "commitments") that characterize CHC, namely: promote and defend human dignity, attend to the whole person, care for the poor and vulnerable persons, promote the common good, act on behalf of justice, steward resources, and act in communion with the Church. This may not be an exhaustive list but it is a relatively basic list that has been accepted and adopted either implicitly or explicitly by CHCOs.

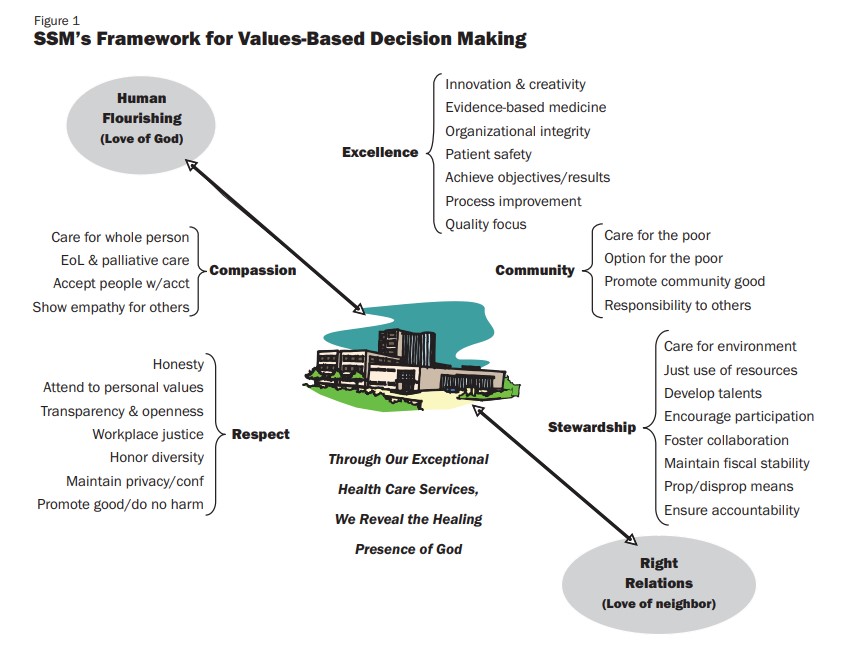

SSM Health Care (SSMHC), based in St. Louis, Missouri,for instance, fairly recently updated its mission and values statement and settled on the following values: respect, compassion, excellence, community, and stewardship. SSMHC's values correspond in one way or another to those listed in the Shared Statement of Identity. Respect corresponds to promote and defend human dignity; compassion correlates to attending to the whole person; community relates to care for the poor and vulnerable persons, promote the common good, and act on behalf of justice; and stewardship corresponds to stewarding resources. Excellence may seem like an outlier but there is a component of it that corresponds to act in communion with the church insofar as integrity is an aspect of excellence.

While helpful for setting the overall tone or orientation of the organization, SSMHC's values, like other organizations' values and those in the shared statement of identity, are often seen as too general to be of much practical use to lay leaders in decision making. What do these values mean to the department manager who has to decide what to do with a longstanding employee who has routinely underachieved? What do they mean to the senior leader who has to decide whether to continue operations at a Catholic hospital that has lost over $80 million in the span of ten years with no end in sight? What do they mean to the critical care physician and nurse who are trying to help a difficult, dysfunctional family accept the reality of their dying loved one's condition and consent to withdrawing unreasonable and inappropriate interventions? The fact is that it is unclear what these values mean in any given context because they lack depth.

Though the values of Catholic health care are multifaceted and far too fluid to standardize for decision making purposes, content can be added to them to better aid decision makers and to drive actions consistent with the values. At SSMHC, for example, leaders at all levels have participated in focused discussions of the values for ethical decision making purposes and provided the following content to each of the values:

Respect: Honesty, attention to personal values, transparency and openness, workplace justice, honoring diversity, maintaining privacy and confidentiality, and promoting the good of others/doing no harm.

Compassion: Care for the whole person, palliative and end-of-life care, accepting people with accountability, and showing empathy for others.

Excellence: Innovation and creativity, evidence-based medicine, organizational integrity, patient safety, achieving objectives/results, process improvement, and a focus on clinical quality and satisfaction (patient, employee, physician).

Community: Care for the poor, option for the poor, promoting community good, and responsibility to others.

Stewardship: Care for the environment, just use of resources, develop talents, encourage participation, foster collaboration, maintain fiscal stability, proportionate/disproportionate means, and ensure accountability.

This more in-depth development of the values comes together with the mission to form a moral framework or lens through which decision makers at SSMHC evaluate concrete situations. This moral framework precedes a decision making process and forms the basis for evaluating the substantive concepts in any process. Basically, the framework outlines the "who" and the "why" related to the character and vision of the organization that in turn informs the "what" and the "how" related to decision making and behavior (see

Figure 1).

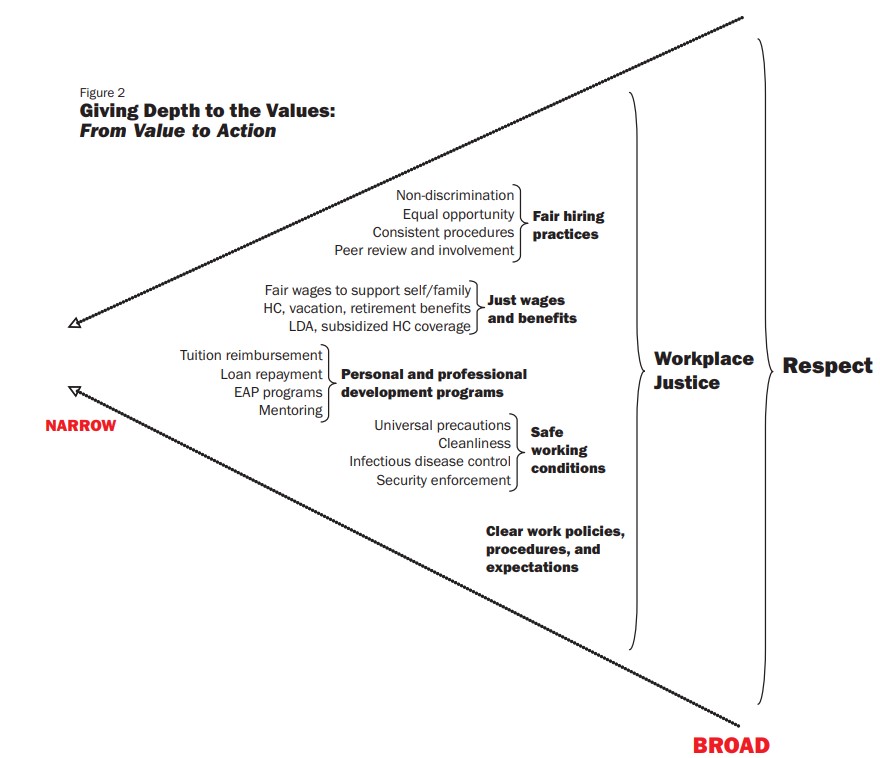

As one might imagine, it is possible to go even deeper in terms of adding content to the elements that fall under the values. Take, for instance, workplace justice, which, on its own, provides very little specificity for how an organization should act vis-à-vis its employees. Drilling down even deeper into the meaning of workplace justice, one might outline additional elements, such as fair hiring practices, just wages and benefits, personal and professional development programs, safe working conditions, and clear work policies, procedures, and expectations. Each of these elements can be further developed such that it results in concrete goals or behaviors necessary for fulfilling the requirement of workplace justice rooted as it is in the value of respect (see Figure 2).

This framework with the added depth to the values pairs with a question-driven reflective process in which decision makers at SSMHC ask: What do our mission/values call us to? What values relate to the issue at-hand? Which are primary and which are secondary? What impact will the decision have on the various stakeholders (individuals, organization, community)?

Now, instead of the department manager trying to figure out what the values mean when addressing a longstanding but underachieving employee and perhaps too simplistically thinking respect and compassion entail just accepting the employee's shortcomings, she can drill down further as to what respect and compassion truly entail and even incorporate other values such as excellence and stewardship. Doing this provides the department manager with insight she might not otherwise have had, such that respect means being honest and upfront with the employee about his deficiencies; compassion means accepting the employee for who he is but holding him accountable for his poor performance; excellence means focusing on performance improvement and expecting results; and stewardship means developing talents but also ensuring accountability. Armed with this understanding of the values, the department manager will not only be honest and empathic but clear about expectations and the consequences for the employee if performance does not improve.

Using the framework and the reflective process outlined above has proven to be very helpful to leaders at SSMHC. In fact, many of the leaders who have participated in the process of adding depth to the values have commented that prior to the exercise the values seemed theoretical and abstract. Now, however, they find that the added depth gives them a better understanding of the values and increases the likelihood that the values can be "operationalized" to the point that they result in consistent behaviors that correspond to particular dimensions of the values. All this, though, has not eliminated disagreement about the most appropriate course of action in certain situations. Leaders at SSMHC have found that using the framework and engaging the process in a group setting does not necessarily result in unanimous agreement, that good people can and will disagree, and that different valid conclusions can be drawn. This is acceptable because the key is not necessarily what the decision is but that the decision follows a reflective process and corresponds to the values and their particular dimensions.

While adding depth to organizational values through focused discussions with leaders throughout the organization can involve a fair amount of work, it ultimately results in greater appreciation for and understanding of the values as well as a level of consistency between mission, values, and behavior at all levels. This is critical for CHC if it is going to be true to its mission and avoid the identity/integrity gap that has plagued so many other organizations in the tough, market-driven environment in which CHC operates.

NOTES

- Brian O'Toole, "Hiring for 'Organizational Fit,'" Health Progress 87, no. 6 (November-December 2006): 38 -42.

- A Shared Statement of Identity for the Catholic Health Ministry, Catholic Health Association of the United States

Copyright © 2009 CHA. Permission granted to CHA-member organizations and Saint Louis University to copy and distribute for educational purposes. For reprint permission, contact Betty Crosby or call (314) 253-3490.