More on Geriatric Dialysis

Several issues ago we raised questions about the growing problem of geriatric dialysis. We noted that it was expensive, ($88,000 a year, all paid for by Medicaid or Medicare), burdensome and less effective with age. We also noted that many physicians — even nephrologists — were reluctant to raise the question of discontinuing dialysis in favor of more conservative treatment.

A recent article in the Boston Globe ("Rethinking Dialysis: Giving Patients Choices," April 17, 2017) cites evidence that suggests the need for a more critical view of dialysis for the frail elderly.

Staff members from Hebrew Senior Life said that it is true that patients get more days with dialysis, "but three days are taken up by dialysis and exhaustion and feeling crummy and you are likely to have several hospitalizations each year due to complications," according to palliative care director Jody Comart. Dr. Ernest Mandel, medical director at Hebrew Senior Life said that too often "dialysis is the default response to kidney failure, occurring without discussion."

Dr. Jane Schell, professor at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, says, "Many patients who have started dialysis, wonder about their prognosis. They want to talk about end of life. We're not asking [patients] ... we're not inviting that discussion."

Given the unlimited funding, the growth and financial interests of the private dialysis industry, and the prevailing assumptions about dialysis, this is a discussion physicians and families should initiate. Like any other treatment that is initially chosen because benefits exceed burdens, there often comes a time when the patient's situation changes and the burden/benefit calculation changes. This is especially true given the rapid advances we are making in palliative care. Asking patients about starting dialysis, or later, about discontinuing it, are important from a clinical, economic and spiritual perspective. Doing so is one more way we can help patients prepare for death.

Health Care Reform: Are Block Grants the Way to Go?

Even though one attempt to repeal the Affordable Care Act failed this month, others are still simmering and may be reintroduced. One aspect of most reform proposals is to replace the current Medicaid funding scheme — which is based on the government sharing a fixed percentage of all Medicaid costs. This means that even if enrollment or costs go up, the government will still provide its percentage.

Block grants would effectively limit the federal government's share to a specific dollar amount, no matter what a state's expenditures are.

A pro and con article appeared in the April 17, 2017, issue of the Wall Street Journal. Hadley Heath Manning, a fellow at the Independent Women's Forum, argued in favor of block grants. She argues that block grants would be more efficient, cheaper and gives states more flexibility. Their primary purpose would not be reducing federal expenditures but to bring about reform (i.e., reducing federal involvement) of Medicaid. She also says that states know the needs of their residents better than anyone else.

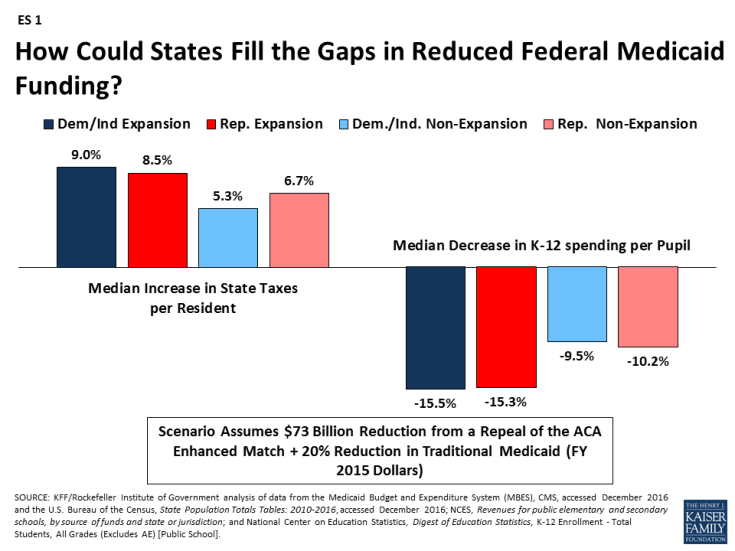

Edwin Park argued against block grants. He agreed with Manning that it would reduce federal expenditures by shifting costs to states, but noted that many people would lose coverage due to more limited eligibility unless states chose to increase taxes or reduce spending in other areas, including education. A graph from the Kaiser Family Foundation (www.kff.org/medicaid) shows results from various proposals.1

"A per-person cap or block grant would leave states on the hook to absorb large and growing federal Medicaid funding cuts — and millions of the least fortunate residents in every state going without health insurance and access to health care," Park concludes.

Catholic social teaching doesn't specify exactly how cost should be allocated, but it is pretty clear that society has responsibility to create an equitable distribution scheme that will provide basic goods like housing, education and health care for all citizens. The problem is that "society" can mean many different things. Many people equate society with government, usually the federal government. This makes fiscal conservatives nervous. Society is not the same as government; rather, it uses one form of government or another in order to achieve its purpose. We use several levels of government in collaboration with private interests to assure these goods are available. It's all a question of subsidiarity which is easier said than done. In practice, it is often difficult to agree on which level of government or what form of public/private collaboration is most effective.

Another problem is that all politics are local, so local officials are much more sensitive to increasing taxes than federal officials whose constituents are far more numerous and also much further away. Even if local (e.g., state) governments could raise enough revenue to sustain Medicaid coverage for everyone who needs it, there would still be the problem of uniformity in payment and quality from one state to another. This is problematic as health care becomes more complex and as many health systems have facilities in a number of different states.

A final problem is that our understanding of health care as a commodity has become so entrenched in our market-driven worldview that it is hard for us to remember that health care itself is a social, collaborative good that does not radically belong to anyone. As Pope Benedict said in his encyclical Caritas in Veritate, a logic of gift, rather than a market logic, must be our starting point.2

Given the shaky financial situation in most states (e.g., Illinois can't even meet its current obligations), shifting more health care expenses to them would put a lot of people at risk. We need to keep a close eye on new repeal and replace proposals to make sure they realize the important ethical values we hold.

Can Physicians Have Consciences?

A recent article by Ronit Stahl and Ezekiel Emanuel argues against expanding conscience exemptions for physicians and other health care providers.3 They see conscience exemptions as an unwarranted expansion of conscientious objection to military service that grew rapidly during the Vietnam War. They cite five characteristics of conscientious objection to military service: it objects to state-mandated conscription; it opposes an unchosen combatant role; it requires "all or nothing" (as opposed to selective) objection; and it disciplines the objector by requiring alternate service or even imprisonment.

These requirements distinguish military objections from private conscience protection provided by the Church amendment (1973) and the Weldon Amendment (2005) to health care providers who are in a freely chosen profession rather than conscripted service. It also differs because these conscience protections allow selective objection to professionally accepted interventions and shield the objector from punishment.

The heart of their argument is that those who invoke conscience protection are neglecting their professional responsibility to act on the patient's behalf and to put the patient's interests ahead of their own. They allow some latitude for "professionally contested interventions" but not for those that are "accepted medical interventions," including abortion and sterilization. "Ending pregnancies is a standard, undisputed medical procedure," they say.

Our tradition agrees with them up to a point. We do not allow a physician to discriminate against persons on the basis of race, or culture, or even illness. And we certainly would allow a physician to opt out of a procedure that he considered to be too risky or unproven. Where we differ is in how we understand "accepted medical interventions." This goes to very fundamental disagreements about human personhood. Direct sterilizations violate our view of the unity of the person. Not everyone accepts the anthropological assumptions upon which this conclusion is based, but it is nevertheless at the heart of our tradition. Abortion is even more serious because it involves the life of a second person. What is at issue here is basic disagreement about the moral status of the early embryo. Emanuel and his colleagues obviously see its status in a different way than we do. This is why for us the conscience exemption is so important: it signals a profound disagreement with prevailing social attitudes about what constitutes a person. In our view, physicians who object in conscience are not derelict in their duties. Rather, they are protecting personal life in a very direct way.

I think we agree with Stahl and Emanuel that the obligation to treat is a very serious one, and should be rarely violated. But we do see a provider's well-formed conscience as sacred and indispensable to carrying out his duty especially in matters where there is no social consensus.

References

- Allison Valentine, Robin Rudowitz, and Don Boyd and Lucy Dadayan (Rockefeller Institute of Government) "How Could States Fill the Gaps in Reduced Federal Medicaid Funding?" Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, Mar 22, 2017.

- "In commercial relationships the principles of gratuitousness and the logic of gift as an expression of gratuitousness can and must find their place within normal economic activity". Caritas in Veritate, Chapter 3, #36.

- "Physicians, Not Conscripts — Conscientious Objection in Health Care", NEJM 376:14, April 6, 2017, 1380-1385. See also a critical response to their article by Wesley J. Smith, "Ezekiel Emanuel Attacks Medical Conscience," National Review (April 7, 2017).

CB

Copyright © 2017 CHA. Permission granted to CHA-member organizations and Saint Louis University to copy and distribute for educational purposes. For reprint permission, contact Betty Crosby or call (314) 253-3490.