Alexandria P. Lescher, DBe*

Jessica Fiorucci Ullrich, MS, DBe*

*co-first authors

Introduction

Many Catholic healthcare systems have programs offering Fertility Awareness Based Methods (FABMs) to patients who wish to become pregnant or limit the frequency/number of pregnancies. FABM services like these accomplish

dual purposes: they allow Catholic healthcare organizations to confront certain operational realities of patients' reproductive healthcare needs while also faithfully implementing ERDs 43, 44, 52, and 53. In reviewing strategies within our own ministries,

however, we noticed that FABMs are targeted only toward women who are working to achieve or avoid pregnancy, despite the potential for benefit beyond this context. Pregnancy-specific approaches to fertility awareness, while satisfactory from

a Catholic moral perspective, miss critical opportunities to support younger and older women, include men as stakeholders, and improve resources for patients who have traditionally had challenges in accessing primary care. We wondered if compliance

with the ERDs has created a false sense of security, leading the ethics community to neglect a further examination of fertility awareness services as a whole — who is offering it, to whom, and under which circumstances.

Current State

FABMs are currently offered in the context of pregnancy alone and isolated from the broader matrix of healthcare services. This creates a perception that fertility awareness is only useful to achieve or avoid pregnancy,

when the advantages of fertility awareness actually begin before puberty and stretch beyond menopause. In reality, pregnancy-centered approaches miss chances to educate patients about the "Fifth Vital Sign" and how one's menstrual cycle provides insight

into overall wellbeing.1 Isolated fertility awareness also pushes men out of a space that could benefit them. When fertility awareness programs leave out these other areas of benefit, they may succeed in satisfying the ERDs but fall short

of promoting human flourishing. When the audience for fertility awareness is focused only on women during child-bearing years, Catholic healthcare systems are unable to live our mission to its fullest or contribute to improving universal health inequities

across care settings. So while offering FABMs within the silo of pregnancy is not necessarily contrary to the ERDs, it may not be the best way to honor them either.

Even when services are appropriately pregnancy-focused, implicit biases may create inequities in who is offered education around the use of FABMs. US culture tends to promote child-bearing in "normative mothers" but to discourage parenthood altogether

for "non-normative" women.2

CHARACTERISTICS OF "NORMATIVE" VS "NON-NORMATIVE" WOMEN

| Normative Mothers are women who meet all of the following criteria: | | A non-normative mother may have any of the following qualities: |

| Married | | Unmarried |

| Able-bodied | | Impaired in any way |

| Heterosexual | | Anything other than heterosexual

|

| White | | Anything other than white

|

Native-English speaking | | Any language other than English |

| Middle- or Upper-Class | | Financially Marginalized |

| Mid 20s | | Any other age |

| Intend to have small families | | Intend to have large families |

| Cisgender | | Non-cisgender |

| Prenatal Care/Healthcare access/Insurance | | |

| Pretty/thin | | |

While social clues may sometimes lead to important information about the patient's health or risk factors, a patient's background or preferences should not be used solely to determine whether the patient is a good candidate for FABMs or not. Guidance

about how to intentionally conceive a child should not be reserved for normative mothers when non-normative mothers are frequently presumed to be unsuitable for FABM and nudged towards pregnancy avoidance. The societal bias between these two groups

has created significant gaps in access to fertility awareness services. Multiple demographics have been left out entirely, including women who do not look like normative mothers, most (if not all) men, and individuals facing barriers around primary

care access. By restricting access to fertility awareness in this way, even unintentionally, everyone who stands to benefit from a broader structure of education is left out, further challenging our ability to promote the true flourishing of our patients.

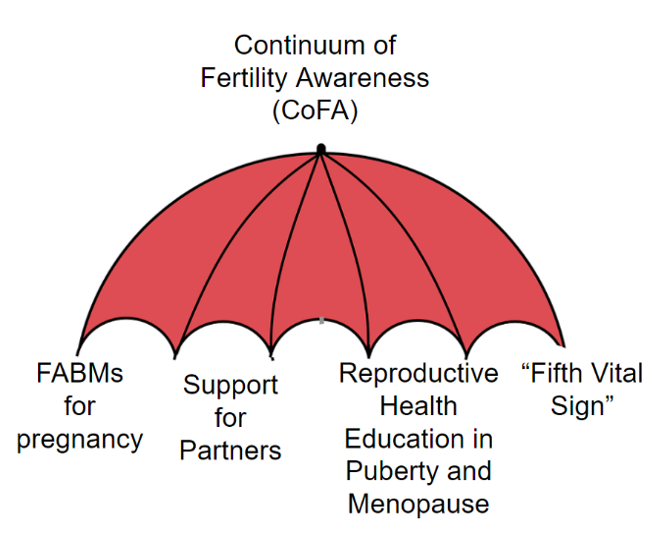

A more comprehensive framework is needed. To address this, we have developed the concept of a Continuum of Fertility Awareness, a field which includes the many ways fertility awareness can serve a patient through the stages of life.

CoFA

In order to provide the best outcomes and opportunities for our patients, we need to zoom out from FABMs that are only offered as a way to achieve or avoid pregnancy. To that end, we have developed the idea of a Continuum of

Fertility Awareness (CoFA), an umbrella term for the multi-faceted field that includes, but is not limited to, methods of family planning. It extends far beyond the short window in a person's life when pregnancy is the main concern. CoFA

considers FABM services as only one part of a holistic, life-spanning approach to reproductive healthcare and develops from there to include the research, educational opportunities, and benefits to be gained by tracking the menstrual cycle from the

beginning of puberty to the completion of menopause. Henceforth, we will use CoFA in referring to this field of work and FABMs when describing specific fertility awareness-based methods used for family planning practices.

In addition to broadening the life stages in which fertility awareness is applicable, framing CoFA as a field of healthcare changes the focus of delivery from only those women who are seen as "good candidates" for FABM to all patients. But doing

so exposes a new question: whether fertility awareness services are being offered to the right groups of people in the right ways or if they are being offered too selectively. And in those spaces where inequities and opportunities exist, CoFA programming

may bring solutions that provide more benefit to a greater number of people.

Specific Opportunities for Improvement

We have identified a few spaces that would be well-served by expanding FABM services into CoFA programs.

Opportunity #1: Support for Partners

Essential conversations about fertility, menstruation, and menopause tend to take place within one of two relationships: between mothers3 and daughters as the elder helps to

guide her child through 'female problems,' or between women and their healthcare providers as the patient navigates gynecological changes. Men are often excluded from such conversations, perhaps because societal stereotypes (Al Bundy and Homer Simpson,

among many) depict them as either not interested in or not responsible enough to share in reproductive decisions.4 Not only do outdated gender roles place disproportionate burdens on women to be the sole educators, monitors, and gatekeepers

of fertility, the stereotypes diminish the thoughtfulness with which many, if not most, men approach their partners and daughters — in short, failing to honor their human dignity. We were inspired by the men we know, who professed to us an interest

in their daughters' health and deep regard for the unity of marriage, which compelled us to craft a framework that acknowledges men as trustworthy stakeholders who deserve increased inclusion. CoFA offers a host of inclusion opportunities, from early

reproductive health education for the boys who will someday grow up to be husbands, to support for fathers who wish to also participate in 'the talk,' to resources for partners who hope to better anticipate and respond to a woman's continuum of needs.

CoFA provides a strategy for parents, couples, and providers that brings more equitable responsibilities to reproductive healthcare.

Opportunity #2: Community Education

Reproductive health education in elementary school, if it is available, typically only covers the changes children should anticipate in puberty. Only 39 states mandate reproductive health

education beyond that, and most of it focuses heavily on the act of sex with the goal of achieving or avoiding pregnancy.5 But the need for information does not stop there, and once people leave school — which could be very early

— there are no further structured educational opportunities. This puts the burden on the individual to seek out the information she needs to understand her body as an adult. It also requires her to know what she doesn't know and then find the

resources needed to fill the gaps, which is unrealistic. Instead of relying on schools or putting the task on women, developing CoFA programs in the community would provide access to information beyond what applies to pregnancy from both medical experts

and other women who have been through similar experiences.

Opportunity #3: Fifth Vital Sign Education

Fertility has become popularized as a fifth vital sign for women, but healthcare has not been so quick to incorporate this approach into practice across age groups.6 If providers only bring up fertility awareness when women are looking to plan for pregnancy, they may unintentionally prevent women and girls from learning a valuable tool in understanding their overall health. When we are not taught to recognize

what is normal for our own bodies, we miss out on clues that can help to identify other issues that may arise. And these aren't just limited to gynecological catastrophes. Irregular cycles and amenorrhea can indicate 'regular' chronic diseases, such

as diabetes or thyroid problems, many of which are treatable but may be difficult to diagnose in women.7, 8 Instead of treating the menstrual cycle as an inconvenience to deal with every month until it is time to become pregnant, teaching

women to track what looks and feels normal can help them identify problems earlier. CoFA programs recognize ovaries and uteruses as organs just like lungs, or eyes, or kidneys, and women should be given information for these organs — just as

they would for any others — in order to advocate for their own health.

Opportunity #4: Reducing Barriers

Patients who are marginalized by 'typical' healthcare delivery may be prevented from accessing fertility awareness services if they are reserved only for the context of pregnancy; rural

populations are particularly susceptible to barriers in access as medical facilities condense into large campuses in lucrative locations; people who prefer a language other than English may encounter difficulties when they must rely on suboptimal

phone-based interpreter services; patients who have never been taught about the clinical, physical aspects of timing pregnancies may feel uncomfortable discussing these things in a medical setting, where it can be challenging to understand medicalese

or know what questions to ask; other patient groups, such as those who are uncomfortable in an office due to physical limitations — who sometimes can't even get into a physician's office or onto an exam table due to lack of accommodations at

that practice — may avoid discussions about timing pregnancies due to the trouble of an in-person visit or the challenge of looking around for a provider willing to make the necessary accommodations. Expanding FABM services into CoFA programs

can help to lessen these well-documented barriers to healthcare access, especially considering that most opportunities for CoFA programming can be provided outside of medical office visits. By teaching people about the benefits of fertility awareness

in a non-medicalized setting from a young age, we can empower women and men, prevent or lessen negative experiences due to various healthcare barriers, and further increase the skills and confidence needed for self-advocacy.

Conclusion

In healthcare, we often feel compelled to make time for only the most pressing, controversial issues. But our own satisfaction with FABMs as a system of family planning that adheres to the ERDS does not excuse ethicists

from neglecting a further examination of its delivery — a simple lack of controversy does not remove the need for scrutiny. Even if FABM services in their current state are enough to 'check the boxes' and meet the criteria set forth by the ERDs,

there are still a number of meaningful opportunities to expand them into something that is truly conducive to human flourishing. This is especially important if FABMs, when offered alone, are contributing to health disparities for the most vulnerable

among us.

Transitioning from FABMs with a focus on pregnancy to CoFA programs that apply to all people changes fertility awareness from a way of gatekeeping reproductive health information into a self-reinforcing, empowering, lifelong service. We recognize that

building CoFA programs will not be without challenges but these meaningful opportunities to improve the lives of so many are certainly worth the effort. Under this new framework, the women who were already benefiting from fertility awareness services

in pregnancy can continue to do so, while men and women at multiple life stages, regardless of limits in access to primary care, will be able to benefit as well. Offering fertility awareness services is clearly not enough anymore; it is time for Catholic

healthcare to explore how these programs can provide for the flourishing of everyone we serve.

Alexandria P. Lescher, DBe

Manager, Clinical Ethics

Ascension Wisconsin

Elkhorn, Wisconsin

[email protected]

Jessica Fiorucci Ullrich, MS, DBe

Manager

Ascension Oklahoma

Tulsa, Oklahoma

[email protected]

ENDNOTES

- Hendrickson-Jack, Lisa, and Lara Briden. The Fifth Vital Sign: Master Your Cycles and Optimize Your Fertility. Fertility Friday Publishing Inc., 2019.

- O'Donohoe, Stephanie, Margaret Hogg, Pauline Maclaran, Lydia Martens, and Lorna Stevens. Motherhoods, Markets and Consumption: The Making of Mothers in Contemporary Western Cultures. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2014.

- See footnote.

- Campo-Engelstein, Lisa. "Raging Hormones, Domestic Incompetence, and Contraceptive Indifference: Narratives Contributing to the Perception That Women Do Not Trust Men to Use Contraception." Culture, Health & Sexuality 15, no. 3 (December

21, 2013): 283–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2012.752106.

- O'Brien, Emilee. "Let's Talk about Sex (Education Inequity)!" Albert Shanker Institute, September 30, 2019. https://www.shankerinstitute.org/blog/lets-talk-about-sex.

- Hendrickson-Jack, Lisa, and Lara Briden. The Fifth Vital Sign: Master Your Cycles and Optimize Your Fertility. Fertility Friday Publishing Inc., 2019.

- "Period Problems." Office on Women's Health. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, March 16, 2018. https://www.womenshealth.gov/menstrual-cycle/period-problems.

- Staff, Mayo Clinic. "Amenorrhea." Patient Care & Health Information > Diseases & Conditions. Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, February 18, 2021. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/amenorrhea/symptoms-causes/syc-20369299