By JULIE MINDA

The coronavirus has had a big impact on pastoral care in Catholic health systems. At the outset of the pandemic, outpatient and elective inpatient services were canceled, or greatly restricted. Hospitals across the country prohibited in-person visits.

In part because personal protective equipment had to be reserved for clinicians early on, chaplains provided their services to patients and their families remotely. By mid-August, as Catholic Health World went to press, inpatient and outpatient services were back, or nearly back to pre-pandemic levels at many facilities.

Fr. John Gaglione suits up in personal protective gear at the Catholic Health COVID-19 Treatment Facility at St. Joseph Campus in Buffalo, New York. He is assisted by nurse Francine Perkins. Fr. Gaglione directs pastoral care services for staff and patients at the facility.

In areas where the virus is not surging, many facilities allow limited visitation for patients without COVID. In these regions, chaplains report that they are seeing many patients for face-to-face visits, but continue to rely on telehealth technology, tablets or smartphones to minister to patients who have COVID, and those awaiting a coronavirus test result.

As caseloads continue to spike in new markets around the country, chaplains must adapt accordingly.

"Our pastoral teams have had to be more flexible, creative and collaborative within our own departments — as well as working with other departments," says Art Maddock, manager of pastoral services for Mercy Northwest Arkansas, part of the Chesterfield, Missouri-based Mercy system. Coronavirus surged in Northwest Arkansas in early July. He says Mercy chaplains use a triage system put in place before the pandemic to ensure they give priority to patients in crisis.

'Anxiety dump'

COVID patients who are critically ill may not be able to converse, but Deacon Ken Potzman, recently retired pastoral care director for Mercy St. Louis, says for patients who are able to communicate their "uncertainty, anxiety, fear and fatigue, spiritual and emotional support are so crucial. Our chaplains have the skills, experience and expertise in this area."

Rev. Jerry Vander Lee of Avera Health says that the pandemic is obliging chaplains to continually reimagine how they offer their presence to patients and families in crisis. The chaplaincy manager of Avera McKennan Hospital & University Health Center in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, says chaplains at Avera "seek opportunities to retain a 'heavenly perspective' in the midst of the deluge of 'earthly concerns' encountered with this pandemic."

Rev. Kayla Parker, right, chaplain resident at St. Mary's Medical Center, discusses a patient with nurse Melinda Barton. St. Mary's is in Huntington, West Virginia.

He says when people talk about their fears, they experience relief. So, he and other chaplains at Avera are seeking to serve as what he calls an "anxiety dump," for patients and staff. "I believe Jesus commands us to care for the most vulnerable, and I might suggest that his intent was to address anxiety and find ways to psychologically transfer the anxiety back to the one that may be in a position to actually do something about it. Transference brings 'hope to light,'" he says.

Rev. Greg Creasy, director of the department of spiritual care and mission at St. Mary's Medical Center in Huntington, West Virginia, says the pandemic has caused many people to slow down and take stock of their faith and priorities in life. Patients and others searching for this kind of insight may be open to deep spiritual conversations that can lead to a spiritual reset, he says.

Rev. Chance Beeler, manager of pastoral and spiritual care for SSM Health St. Joseph Hospital — St. Charles, in Missouri, says chaplains practice active listening and have the ability to help people to name their feelings. He says the chaplains he works with do not expect patients to seek them out — the chaplains are trying to check in with as many people as they can at the hospital.

Rev. Beeler says regardless of whether people have a faith tradition or not, they are very welcoming of the chaplains' presence. "We're spending a lot of time talking with patients. They want to talk to us. They are not seeing their family and friends to the extent that they were before the pandemic, and it's important to be available to them. They are wondering what the future holds and it is important to be there with them."

"We have the chance to humbly represent God's presence in these sacred moments," adds Mary Salois. She manages mission and pastoral services for Mercy health system's Washington, Missouri, hospital and for several dozen of its nearby clinics.

In the know

Chaplains interviewed for this article say their pastoral care departments have been part of the operational incident command planning that their hospitals have been conducting around COVID since late February or early March and that has allowed them to adapt their work to meet changing protocols and workloads related to the pandemic. While the incident command groups are not meeting as often as in the past, when they do convene, chaplains are part of the conversation.

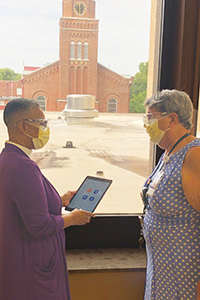

Rev. Beverly Stith, left, and Rev. Gail Holstein converse at SSM Health St. Joseph Hospital – St. Charles in Missouri, where they are chaplains.

Rev. Beeler says though visitation has resumed to a limited degree — SSM Health St. Joseph allows one or two guests per patient per day for COVID-negative patients — many patients are still distant from loved ones, and so the chaplain presence remains crucial for emotional and spiritual support.

Deacon Potzman says in another effort to soften isolation, chaplains at Mercy St. Louis are in phone contact with patients quarantined at home.

Rev. Creasy says St. Mary's Medical Center chaplains are using phone and video chats to check in with COVID patients' loved ones as well.

Rev. Vander Lee adds that, during the strict visitor restrictions, Avera McKennan chaplains were communicating more frequently with the clergy of patients' home churches. The hospital chaplains have found the clergy sometimes see the chaplains as ministering on their behalf, including by assuring the patients their fellow parishioners had not forgotten them during the visitor prohibition.

Presence — live and virtual

The chaplains say their hospitals have kept a live chaplain presence even when chaplains' in-person visits to patients were paused. Now their reliance on telehealth equipment and personal technology is lessening as they resume in-person visits. But the experience with virtual visits showed that interpersonal communications skills play differently via video than they do face to face.

James Austin is a chaplain with Mercy Virtual Care in Chesterfield, Missouri. His usual role is to provide tele-chaplaincy throughout Mercy's four-state network. Since the pandemic's start, in addition to that responsibility, he's been coaching chaplains and other colleagues throughout the system to adjust their communication style to the virtual environment.

He says, "When pastoral care cannot rely on being physically present in the room to provide care, other gifts and talents must be brought to bear — listening skills, match and pacing, eye contact, visual cues, etcetera." For instance, he says, the "sacred pause" — the silence that chaplains and therapists often use in-person to invite input from their clients — does not work as well in a virtual format. Learning how to "fill the space while keeping it open" is a skill that some chaplains are having to develop.

Amid much ongoing stress, chaplains help one another to cope

Chaplains throughout the Catholic health ministry have been serving as a type of stress release valve for hospital staff who are feeling burned out by the pandemic and for COVID-19 patients who may fear for their lives. In the process, chaplains are making themselves vulnerable to the same type of emotional and spiritual distress that they are trying to shield others from.

To help stave off their own burnout, a sampling of chaplains throughout the ministry say they are tending to their own spiritual well-being and that of their peers. Spiritual distress and empathy fatigue is an occupational hazard for chaplains, and that is especially true now in the emotionally wrought days of the pandemic. By leaning on one another, and by practicing the same self-care skills they preach to others, they say they are fortifying themselves for the long haul.

"Our work is very draining, and we're feeling frustration," says Rev. Greg Creasy, director of the department of spiritual care and mission at St. Mary's Medical Center in Huntington, West Virginia. "We need time to debrief, rest and refocus."

Depository of anxiety

Rev. Jerry Vander Lee is chaplaincy manager of Avera McKennan Hospital & University Health Center in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. Citing a concept used by author Heije Faber, Rev. Vander Lee says the hospital chaplain is a little like a circus clown — just as a clown goes anywhere in a circus and fills the gaps, so too does a chaplain go throughout the hospital "with a grasp of the tragedy and comedies of life." In the case of chaplains, though, they are identifying spiritual needs, and helping to address them.

He says chaplains can absorb stress and anxiety as they offer their support. Supportive human connection remains paramount to release this weight and tension. "It does not matter how we connect — as long as we connect and remain connected," he says.

That accumulated empathy burden was a particular concern for chaplaincy departments that had to temporarily furlough staff amid budget or managed patient volume reductions to free up capacity to treat COVID-19 patients. Most hospitals also discontinued in-hospital volunteerism, including that of eucharistic ministers, at least for a time, adding to the job duties shouldered by chaplains.

In it together

Rev. Creasy says the chaplains on his pastoral care team meet at least daily to talk about what they are experiencing and feeling. He encourages chaplains to use the same methods they teach others to renew their own spirits. This includes rest, attending worship services (either virtually or where safe social distancing is practiced) and walking outdoors. He rejuvenates in his off-hours by tinkering with projects around the house.

Rev. Chance Beeler says it has been helpful to the chaplains on his pastoral and spiritual care team at SSM Health St. Joseph Hospital – St. Charles to check in on each other and to talk about the things that "are life-giving to them" — their families, pets, hobbies and spiritual practices.

Rev. Beeler says his colleagues find inspiration in the story of the Franciscan Sisters of Mary who founded many of SSM's legacy ministries at a time when smallpox was rampant. "We're in the midst of a pandemic too, and we know we can continue courageously even when we are afraid — after all those sisters did the same, but with no resources, no money."

Know yourself

Rev. Vander Lee says that chaplains are individuals with different coping skills and flash points. "It is important for chaplains to know themselves and what might trigger their own anxiety," he says. Many of the chaplains he works with are introverts. Rev. Vander Lee says it has been helpful to them to have alone time for reflection, devotion, relaxation and rejuvenation.

"One should seek opportunities that are consistent with one's personality," he says.