By LISA EISENHAUER

As summer was winding down, Dr. Celeste Caballero was experiencing firsthand the results of the nation's having let down its collective guard against COVID-19 in the spring when case numbers were falling and vaccines were becoming widely available.

Caballero

"I can tell you what I'm seeing on the front lines right now with COVID and children is very concerning," said Caballero, a pediatrician with Covenant Health who works at the only pediatric urgent care in Lubbock, Texas. Covenant Health is part of Providence St. Joseph Health.

What Caballero was seeing in early September was two to three times as many children being brought in for testing because of suspected COVID exposure compared to last year and many grade schoolers and teenagers testing positive.

National figures back up what Caballero and pediatricians at Catholic health ministries elsewhere reported: that the late-summer COVID surge was taking a much harsher toll on children than previous surges did.

A couple visit their 4-year-old daughter as she's recovering from COVID-19 at The Children's Hospital of San Antonio, where her treatment included some time on a ventilator. The parents, who declined to share their full names, appear in a video that is posted on the hospital's Facebook page. It urges parents not to ignore symptoms of COVID in their children and calls on everyone who can to get vaccinated.

The Children's Hospital of San Antonio

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that from the start of COVID case tracking through Sept. 15, Americans age 17 and younger made up about 14% of cases despite being about 22% of the population.

However, for the week that ended Sept. 9, the American Academy of Pediatrics found that children represented about 29% of reported COVID cases, with 243,000 pediatric cases added just that week. (The academy was using state data that varies in terms of who counts as a child; some states categorize those as old as 20 as children and in some states the cutoff is age 14.)

CDC figures show that COVID's toll on children has been much worse on those who are not white. For white Americans through age 17, the hospitalization rate for COVID is 23.2 per 100,000 in the population. By comparison, the rate for non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native is 85.7; for Blacks it's 77.3; and for Hispanics it's 79.8.

Trifecta of needs

Mark Wietecha, chief executive of the Children's Hospital Association, said weekly COVID case counts among children were below 10,000 in June. "So, it's an exponential climb," Wietecha said of the latest numbers, "and we've now exceeded the previous high level, which was January."

Wietecha

He noted that the COVID numbers for children are spiking at the same time that children's hospitals are seeing a surge in respiratory syncytial virus (commonly known as RSV) and other respiratory illnesses as well as heavy demand for behavioral and mental health care.

"The three combined have really served to sort of pile up the hospitals pretty substantially," Wietecha said.

Dr. Marya Strand said that SSM Health Cardinal Glennon Children's Hospital in St. Louis, where she is chief medical officer, was "atypically busy" in early September. Strand said it wasn't so much that COVID cases were stressing the hospital's resources; it was just the overall number of kids in need of acute care with viral illnesses, traumatic injuries, chronic conditions such as complications from diabetes, and behavioral issues.

Strand

As at other pediatric hospitals, she said Cardinal Glennon was seeing a spike in viral illnesses. The increase began in the summer as kids headed off to camps and regrouped for social events like parties that weren't happening early in the pandemic. Strand said she and her colleagues worried that with schools just starting to reopen, the spread of viruses would only get worse.

COVID was especially worrisome because delta, the most prevalent strain, has proven to spread more easily than earlier versions of the virus.

"I think that it's particularly treacherous to have that highly contagious variant at a time when kids are going back to school and getting into bigger groups together, particularly if we are not asking them to wear masks in such a circumstance," Strand said.

Mitigation methods worked

Dr. Melissa Puffenbarger, medical director for the emergency department at Mercy Children's Hospital St. Louis, said that early in the pandemic her hospital was on trend with other children's hospitals in seeing a sharp drop in patients. Typically, her department sees 60-90 children a day. One day in March 2020, it saw nine, as fears of infection kept patients from coming into facilities for care.

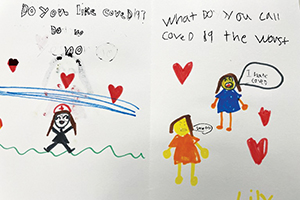

A second-grade class from Rogers Elementary School in Waterloo, Illinois, sent this drawing along with other thank-you cards and notes of encouragement to frontline health care workers at SSM Health Cardinal Glennon Children's Hospital in St. Louis.

By early September, the patient count had rebounded. On Labor Day, Mercy Children's had 94 patients in its ED.

Many of the patients in late summer came to the hospital for respiratory illnesses. The results from one week of full panel tests that were run on those patients found 32% were positive for RSV, 26% for rhino enterovirus and about 10% for COVID.

One illness most of the hospitals are not detecting yet is flu. But like others, Puffenbarger expressed concerns that when what is typically flu season starts later in the year, it could be especially harsh.

Puffenbarger said 2020, when relatively few children came down with COVID or other respiratory illnesses, had proved a case study for the effectiveness of measures such as distancing and masking to check the spread of such diseases.

"It just showed that our mitigation methods worked pretty significantly and that's why flu went away, and RSV went away," she said.

Puffenbarger is concerned about what's still to come, with many schools having just resumed in-person classes and with many of them not requiring masks or enforcing other precautions.

"I think the thing that makes me the most sad is that COVID containment measures within schools have been politicized and in certain states you are seeing that public funding for education is being affected by those decisions, which to me is just absolutely appalling," Puffenbarger said. "The only people that they are punishing are the children that need to be educated and need to be in school."

Enabling wider COVID spread

Even with the COVID case counts among the young rising, serious cases of the illness in children remain rare. A CDC surveillance system that monitors COVID cases in 14 states shows that few of those 17 and under who have been infected have required hospitalization. Most kids are sent home to quarantine and recover.

The fact that the virus in general has a milder impact on its youngest victims should come as no comfort, said pediatricians. The continued spread of the virus poses risks across communities and the only way to reduce those risks is to prevent the spread, they said.

Just as doctors are reporting for the adult population, pediatricians say the COVID patients they are seeing who have the most serious cases and who are old enough to have gotten vaccinations almost uniformly have not. They said many parents cite concerns about adverse effects from the shots.

Carlson

Asked whether he or his colleagues at HSHS St. John's Children's Hospital in Springfield, Illinois, had seen any signs of severe reactions to vaccines among patients, Medical Director Dr. Douglas Carlson said: "No, not a one." HSHS St. John's is part of the Hospital Sisters Health System.

Carlson said in addition to generally having milder symptoms when infected with COVID, children age 9 and younger seem to share it less. "It has to do with body size," he said. "Those younger when they cough or breathe are probably not spreading it a lot, but once you get to 10 it looks like it's about the adult rate of spreading."

Carlson credited a comparatively high rate of vaccination in the central Illinois region that his hospital serves for keeping COVID cases lower in late summer than in other regions of the country. He nevertheless feared that a surge of the virus could be in the offing.

"Our hospital is nearing capacity with RSV, other infections and injuries," he said. "We can't afford to have COVID also on top of that."

Low vaccinate rates a factor

Caballero said the COVID spike in Texas correlates with its relatively low vaccination rate. In Lubbock County, 55% of residents 12 and above had gotten at least one dose of vaccine and 46% were fully vaccinated by early September. Across Texas, the numbers are a bit higher: 58% with one dose and 49% fully vaccinated.

Like other pediatricians, she said vaccines coupled with masking, social distancing and hand hygiene were the best hope for keeping children from getting COVID and for halting its spread in communities.

Caballero said: "My advice and my plea to the parents is: Please know that COVID is an illness that can affect children and is infecting children this fall, and it is imperative that we come together as a community and get vaccinated for COVID because this is our hope to end this pandemic and this is our hope to protect our children."

Sudden COVID surge catches San Antonio hospital by surprise

Until this summer, The Children's Hospital of San Antonio had weathered the COVID-19 pandemic without going into surge mode.

Christopher

The CHRISTUS Health hospital wasn't seeing many patients with the virus and overall demand for care was generally below capacity, said Dr. Norm Christopher, its chief medical officer and vice president of pediatric emergency services.

That changed when the delta variant of the coronavirus began sweeping across Texas along with an unseasonal epidemic of other viral infections such as respiratory syncytial virus and influenza. Suddenly the hospital's beds were filling, and its primary care centers, urgent cares and emergency rooms were inundated.

Six-year-old Christopher Gantt is held down by his mother, Jennifer Gantt, during a nasal swab to test for COVID-19 in the emergency department of The Children's Hospital of San Antonio.

Meridith Kohut/The New York Times/Redux

"I think it caught all of us off guard a little bit," Christopher said. "We in the children's space had not seen children impacted in the early part of the pandemic and when this delta variant became more disseminated in the community, we saw volumes increase. I don't want to be dramatic and say overnight, but it was very, very quickly."

The summer volume of patients, typically the lowest of the year, this year has already equaled or surpassed what is historically seen in the height of the peak winter seasons, he said in mid-September.

The care of the vast majority of the hospital's COVID patients has been manageable on an outpatient basis, Christopher said. Despite that, the number needing hospitalization pushed The Children's Hospital to adopt surge protocols in mid-summer. He estimated that about 10–15% of inpatients were there because of COVID.

As part of being in surge mode, the hospital's physician and nursing leaders huddle three times a day to evaluate capacity. The discussions focus on patient flow and throughput in the hospital's various units and assessing whether inpatients can be moved to lower levels of care.

A major factor in accommodating patients is staffing,

Christopher said. Because of shortages of pediatric nurses and other providers trained in pediatric care, the hospital has had to leave up to 30% of beds in some units vacant at various times.

Christopher said that even when The Children's Hospital hasn't been able to accept patients, its clinicians have consulted on the patients' treatment with their counterparts at the facilities where the patients were getting care.

As summer was winding down, the hospital had gotten something of a reprieve in its patient load, Christopher reported. By mid-September, it was finding beds for most patients in need of hospitalization.

He didn't want to speculate on whether demand was actually beginning to wane or whether the surge would continue into the fall.

He noted that the hospital's administrative and clinical leaders were doing what they could to rally staff's spirits and recruit more workers, but exhaustion was apparent. "It's a delicate time," he said.

— LISA EISENHAUER

Children's Hospital Association presses for federal aid

The first year of the COVID-19 pandemic was so financially challenging for its members that the Children's Hospital Association

issued a report in March that said: "Children's hospitals as a major anchor of the national safety net infrastructure for children are at risk."

The report projected that revenues to children's hospitals nationwide would be down $5 billion for fiscal year 2020 from the previous one. Fiscal year end dates vary by institution but are commonly June 30, Sept. 30 or Dec. 31. Federal disaster relief from the Provider Relief Fund was expected to offset over $3 billion of that loss, still "leaving a large negative impact on children's hospitals."

Mark Wietecha is chief executive of the association, which has more than 220 member hospitals. He said the drop in patient count driving those losses in fiscal 2020 had reversed by late this summer.

In fact, he said, some children's hospitals were at risk of being overwhelmed with COVID-19 patients and those with other viral respiratory illnesses and with children in need of behavioral and mental health care. He said much of the demand for that latter care was related to the isolation and other social issues exacerbated by the pandemic.

On top of the surge in patients, Wietecha said children's hospitals are dealing with the same shortage of staff that is plaguing health care providers across the nation. The challenge is heightened in the pediatric sector, he said, because care providers need special training and the pool of qualified applicants is smaller.

"I think the financial picture is not as dire (as last year) but the operational picture is kind of distressed," Wietecha said. "We just have too many kids and inadequate numbers of staff."

His organization is lobbying the Biden administration for additional assistance. In a letter to the administration Aug. 26, the association said: "We ask for immediate support for pandemic-driven staffing cost increases through federal pediatric emergency assistance, specifically the release of provider relief funding and any other federal workforce support that can be quickly distributed and targeted to pediatric crisis response."

The group also is urging passage of two measures in Congress. One would fund infrastructure and training for pediatric mental health care; the other would provide grants to improve pediatric care capacity and dedicate funding for national pediatric preparedness response investments.

"We just have a multiple set of problems to tackle and we're going to need some federal help to do that," Wietecha said.

— LISA EISENHAUER