By JULIE MINDA

As employers have shut down or scaled back their businesses because of pandemic impacts, job insecurity has increased, with low-wage, hourly workers impacted most. Lacking money for food, high numbers of people have been seeking emergency food aid.

Cars line up in the parking lot at a drive-thru food pantry at Woodland Mall in Grand Rapids, Michigan, in April 2020. There has been a high demand for food aid since the outset of the pandemic.

Neil Blake/The Grand Rapids Press via AP

While government and private aid has helped address food insecurity in the U.S., food demand remains high, according to a sampling of leaders from the health care, social service and academic fields. Those leaders said the needs of the hungry — needs that go well beyond sustenance — highlight the necessity for broad systemic change that involves partnerships between governmental and private agencies to address root causes of food insecurity.

Sumilas

"We need to make sure that our systems are fair," Michele Sumilas told the participants in "The Face of the Person Who is Hungry," a virtual conference convened by Pittsburgh's Duquesne University School of Nursing in the fall. She was executive director of the Washington, D.C.-based Bread for the World advocacy organization when she spoke at the conference. She is now assistant to the administrator of the bureau for policy, planning, and learning at the United States Agency for International Development.

Stenson

Spiked demand

Jane Stenson is vice president of food and nutrition and poverty reduction strategies at Catholic Charities USA. Food aid is the agency's biggest service. Stenson said when the pandemic hit, "the demand for food skyrocketed," partly because of panic buying, and "the food distribution system was out of whack, with grocery store shelves empty, food pantries empty."

While food insecurity was relatively stable just before the pandemic, Stenson said that many people became newly food insecure last spring. Scurrying to figure out how to implement new infection control protocols, lacking personal protective equipment and with supply chains disrupted by the pandemic, many food pantries initially had trouble responding to the crush of demand.

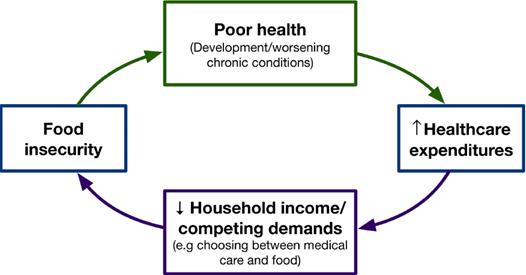

This model conceptualizes the relationship between food insecurity and health care expenditures. The figure appeared in a Feb. 17 article, "Examining the bidirectional relationship between food insecurity and healthcare spending," in Health Services Research.

Layoffs, furloughs and work hour reductions had cut into affected workers' household food budgets. According to "Unemployed Without a Net," a September brief from researchers at Harvard Kennedy School's Malcolm Wiener Center for Social Policy, unemployment jumped from 4% in February to 15% in April. "The economic toll of the coronavirus outbreak has been particularly severe for service sector workers," including those in retail, food service and hospitality, the researchers wrote.

According to "The Impact of the Coronavirus on Food Insecurity in 2020," an October report from the nonprofit hunger relief agency Feeding America, before the pandemic, there were more than 35 million people who were food insecure, and this was the lowest U.S. food insecurity level in more than two decades.

Feeding America estimated that about 50 million people experienced food insecurity in 2020. The organization said in a December press release that its national network of food banks had continued to consistently report a nearly 60% increase in demand compared to the previous year and continues to require more food and resources to provide to people in need.

Stenson said significant influxes of governmental aid and philanthropic relief (see sidebar) have provided temporary help for individuals and families facing food insecurity. Despite that aid, demand for food is still high, she said.

Gormley

Interconnected issues

Duquesne University President Ken Gormley told participants at the Duquesne nursing school symposium on hunger that the pandemic worsened preexisting basic inequalities. He said the vulnerable populations hit hardest by the pandemic are reeling from a complex set of interconnected problems, including financial hardship, medical costs, housing insecurity, social isolation and hunger. Speaking specifically about hunger, he said, "food insecurity is a growing concern worldwide, and families and individuals are being forced to make very difficult decisions."

A Feb. 17 article in Health Services Research, "Examining the bidirectional relationship between food insecurity and healthcare spending," delves into one aspect of the interlocking issues — food and health. The authors analyzed data on health care expenditures, food insecurity and medical conditions for 10,886 adults included in surveying in 2016 and 2017. The authors concluded that being food insecure in one year was associated with higher odds in the next year of having greater total health care expenditures. The authors also found that having greater health care expenditures in one year was associated with slightly higher odds of being food insecure in the next year.

Based on their analysis, the authors concluded that disease management plans targeting the upstream determinants of food insecurity and general poor health may be more effective at breaking the food insecurity-poor health cycle than interventions that solely target disease management costs.

Advocacy with partners

Kathy Curran is CHA senior director of public policy. She said as a symposium panelist that the pandemic has laid bare how interconnected America's food concerns are with federal, state and local policy in numerous areas. These include lawmaking around unemployment benefits, aid packages, health care, banking, education, job creation and technology. Given that health is so strongly linked to nutrition and other social factors, CHA works closely with Catholic partners and other allies on a range of policy issues to advocate for social justice.

Sumilas agreed on the vital importance of advocacy to affect these systems for change. She said that inequities worsened by policies at many different levels and in many different areas of government can have dire consequences for vulnerable people.

Working with partner organizations on advocacy efforts, building relationships and trust with lawmakers and presenting data and personal stories that illustrate the gravity of the inequities can help to bring about real change, she told the audience.

"As Christians we are obliged to use our power to urge change when it comes to the things Jesus told us to care about," including hunger, Sumilas said.

Federal government moves improve food security

During the pandemic, several federal actions have had a significant impact on food insecurity and related concerns:

- Signed into law in March 2020, the Families First Coronavirus Response Act included additional funding for the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children and for a Commodity Assistance Program that was part of the Emergency Food Assistance Program. That act also funded nutrition services for Aging and Disability Services Programs. And it waived some requirements so that it would be easier to get food to schoolchildren and to people dependent on SNAP.

- A second law adopted in March was the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act, which provided a stimulus payment of up to $1,200 for individuals, $2,400 for joint taxpayers and an additional $500 for each qualifying child. That law also increased unemployment payments by $600 weekly through July 31.

- In December, a new COVID relief deal was passed into law under omnibus appropriations legislation that increased the maximum benefit allowed under SNAP and increased the amount of aid provided under the Emergency Food Assistance Program. It increased funding for food for very young children, school children and older adults. It also provided a payment of $600 for people earning up to $75,000 annually and a payment of $1,200 for couples earning up to $150,000 annually, along with $600 per child in a household. It provided an additional $300 weekly in federal aid to unemployed people through March 14.

- In January, President Joe Biden signed executive orders to increase SNAP aid for women, infants and children. The order also increases monetary aid to families with children who have lost access to food aid due to school and childcare closures, through the Pandemic Electronic Benefits Transfer program. The order also aims to improve the SNAP program to better address recipients' needs.