By RENEE STOVSKY

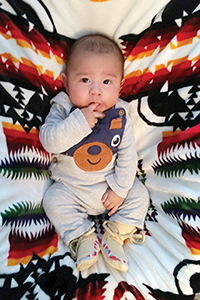

Valen Biglefthand sports handmade beaded moccasins. His mother Vania Biglefthand made the booties in a crafts class while she was on bed rest at St. Vincent Healthcare in Billings, Mont.

Vania Biglefthand, 33, was 30 weeks pregnant with her third child when she began bleeding the night of Sept. 19, 2017. She and her husband, Ray, 40, rushed to St. Vincent Healthcare in Billings, Mont., a two-hour drive from their home in Colstrip, Mont. Doctors discovered a rupture in her amniotic sack. To stop her labor and address the possibility of infection, clincians gave her a steroid shot and antibiotics. She was admitted to the hospital, where she remained on bed rest for the duration of her pregnancy.

Biglefthand remembers that time as trying, both physically and emotionally.

"My back and tailbone hurt, and the bigger I got, the harder it was to sit still," she says. "I was very restless, and I missed my two sons. And, of course, I worried constantly about the health of the baby."

Though her husband brought Nathan, 11, and Ethan, 9, for visits every few days, Biglefthand, a certified nursing assistant, knew she needed to do more than watch TV to keep her attitude positive. So, when a case manager told her she could attend classes — provided she did so in a wheelchair — she enthusiastically signed on. The March of Dimes sponsors the classes for neonatal intensive care unit families.

Soon she was engaged in a variety of programs, from blanket making to scrap booking and infant massage. But the class she says she most looked forward to was one offering lessons on moccasin making.

Accent the positive

Kassie Runsabove, health disparities coordinator at St. Vincent Healthcare, created the class last summer. "I was looking for a way to work with our tribal communities and engage them in a positive way," says Runsabove, who is herself a White Clay Cree.

Inconsistent prenatal care likely plays a role in the high incidence of very low birth weight babies among the Native American population in Montana, Runsabove says. "We have 12 tribes and seven reservations here in Montana, and many mothers do not get prenatal care past 28 weeks gestation because of distance, time and finances."

The Crow Reservation and the Lame Deer Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation are within St. Vincent's sprawling catchment area. The Crow Reservation is about 50 miles from the hospital; parts of the Cheyenne reservation are 200 miles away. Runsabove explains the Indian Health Service provides prenatal care on the reservations, but only does so up to 28 weeks gestation because it does not have obstetric services.

At that point, women are referred to obstetricians connected to one of the two Billings hospitals with maternity services. Some women discontinue regular prenatal visits at that point. Some women who have had prior pregnancies may not be diligent about seeking prenatal care on the reservation early in their pregnancies because they know the provider will not be delivering their baby, Runsabove says.

Kassie Runsabove, health disparities coordinator at St. Vincent Healthcare, works with a pattern for a baby moccasin. She started a moccasin making class last summer to help connect in a culturally sensitive way with Native American parents whose babies are patients in the hospital's neonatal intensive care unit.

Her hope is that by connecting with Native American families in the NICU in a culturally sensitive way, St. Vincent will encourage these women to seek continuous prenatal care in their subsequent pregnancies, and influence their friends and families to do so.

Stitching and beading the moccasins has a direct benefit too. It can help NICU parents remain focused on positive outcomes for their infants during lengthy hospital stays.

Because moccasin making is a common tradition among various Plains tribes, Runsabove sees it as a way to not only break down barriers and build confidence between cultures but also to honor heritages and reintroduce spiritual values. "Our mission here is to foster God's healing love," she says.

Ties that bind

To prepare for the program, Runsabove says she spent $530 on a buckskin hide, beads, wax, thread and needles. Then she made a pattern for the soles, tops, laces and tongues of the moccasins — sized to fit an average 3-month-old baby — and cut out 60 kits.

"In class, I demonstrate the process of beading and give parents the tools and materials to make the moccasins, but I also encourage people to go back to their mothers, aunties and tribal elders to learn traditional patterns they can use in their designs," she says. "It's a way to encourage families to come together during a challenging but very special time."

Unlike many class participants, Biglefthand had had some previous beading experience, and had watched her mother bead leggings, belts and dress yokes. Still, she says she found the project difficult, because moccasins are not symmetrical. "You have to eyeball and measure where to start the designs," she says.

If the shoe fits

Since she and her husband have Crow, Northern Cheyenne and Navajo ancestry, she knew she wanted to incorporate trademark designs like squares, triangles or circles in her work. "Other tribes have more flowery patterns; ours are more geometric," she says. She decided to use red, white and blue beads since she didn't know the gender of her baby.

All in all, she estimates the project took eight hours, and says sewing together the various pieces was "nerve-wracking." "I was hoping and praying it would come out right," she adds.

Vania Biglefthand learned how to make the baby booties shown in the inset above in a crafts class at St. Vincent Healthcare. She is shown here during a visit with her husband Ray and sons Ethan, 9, center left, and Nathan, 11, during the month she spent at the hospital prior to her delivery.

Biglefthand says she felt a real sense of accomplishment when she finished her baby's moccasins. "I was excited to gift something I made myself, instead of something I bought, to my baby. And the process of creating it kept me busy so I wasn't thinking about the 'what ifs' that come with having a baby before the due date."

Biglefthand had been receiving regular prenatal care and was healthy throughout her pregnancy, Runsabove says. As things turned out, Biglefthand delivered her third son, Valen, on Oct. 13, 2017, after a month of bed rest. He weighed in at 4 lbs., 10 oz. and measured 17 inches long. After 16 days in the St. Vincent's NICU, he went home. At three months, he was 11 lbs., 2 oz. and 21 inches long, and almost big enough to wear his new moccasins, though his mother admits he spends a lot of time kicking them off.

Motivating mothers to get prenatal care

That's exactly the kind of positive outcome Runsabove and Jennifer Eliason, March of Dimes NICU family support coordinator, aim for with the program.

"In St. Vincent's NICU, 25 percent of all babies admitted at less than 3 pounds are Native American, but only 10 percent of Montana's population is Native American," says Eliason. "That's a huge disparity, and our hope is that experiences like this will help encourage expectant families to seek out earlier care."

Since it began in August, Runsabove has added another traditional craft to the class — the art of making belly button holders. A simpler project than moccasins, the buckskin pouches are decorated with either lizard designs for boys or turtle designs for girls. Some tribes believe that sewing the baby's umbilical cord inside the pouch and keeping it in the family's home will not only protect the baby but also connect him or her not only to mother, but also Mother Earth.

Bethany and Alex Lawson with daughter Abigail. Alex Lawson made a pair of beaded moccasins for Abigail.

And Runsabove has found that not only Native American expectant parents are interested in learning how to make these traditional crafts.

Handmade keepsakes

Alex Lawson, 26, of Billings, took Runsabove's class in September, shortly after his wife, Bethany, 24, gave birth to their daughter, Abigail Parker Lawson, at St. Vincent. Bethany had been on bed rest for a month there and delivered six weeks early; Abigail spent four weeks in the NICU before she was able to go home.

"While my wife was busy feeding and holding the baby, I decided to take the class," says Lawson, a motorcycle mechanic and technical pastor and director for Harvest Church in Billings. "Kassie explained the culture behind the moccasins and then showed us how to bead correctly and tie the string into the lip of the shoe."

Lawson decided to bead his little girl's initials onto her moccasins instead of attempting a more difficult tribal design. In mid-February, she'd grown from 5 lbs., 2 oz. to a robust 15 pounds, and was just about able to wear his creation. Now he says he'd like to make another pair "for when she starts walking."

In the meantime, he's busy making a keepsake chest to put all her NICU mementos in — including the moccasins — and plans to give it to Abigail when she's 18 years old.

Copyright © 2018 by the Catholic Health Association

of the United States

For reprint permission, contact Betty Crosby or call (314) 253-3490.