Food insecurity can be gateway to lifelong health problems

By DALE SINGER

When you're trying to change someone's behavior, it's easier to use incentives than punishments — carrots, not sticks.

In furthering PeaceHealth's efforts to combat malnutrition among families in the Pacific Northwest, Meghan McCarthy suggests literal carrots — or broccoli, or asparagus, or any healthy vegetable favored by kids — be offered at meal and snack times instead of fat or sugar-dense treats. If that sounds simple, it's not. Fresh vegetables and fruits can be hard to come by in low-income neighborhoods.

In partnership with PeaceHealth, the FOOD for Lane County Youth Farm, a Community Supported Agriculture Program, runs an organic produce stand at PeaceHealth Sacred Heart Medical Center at RiverBend in Springfield, Ore. It is open on Thursday afternoons in the growing season. The Youth Farm provides its teenage crewmembers with training in gardening, nutrition, leadership and financial management.

As system director of community health at PeaceHealth, McCarthy is spearheading a drive to educate the public on the connections between a poor diet and a range of bad side effects that can include poor school performance, a weakened immune response, higher stress levels, and the onset of chronic diseases like obesity and diabetes.

"This is a problem that is facing all America," she said of poor nutrition. "I don't think you would find a physician anywhere in the United States that isn't worried about patients not eating well."

Food insecurity

Eating healthfully is a particular challenge for families who endure food insecurity, McCarthy said. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, in 2017, an estimated 11.8 percent of U.S. households were food insecure at some point during the year and 4.5 percent of households experienced very low food security. Food insecurity is characterized by a lack of consistent, sufficient and varied nutrition — family members may eat lower quality foods to make their food budget stretch, but people generally don't go hungry. In households with very low food security, there may be intermittent hunger.

McCarthy

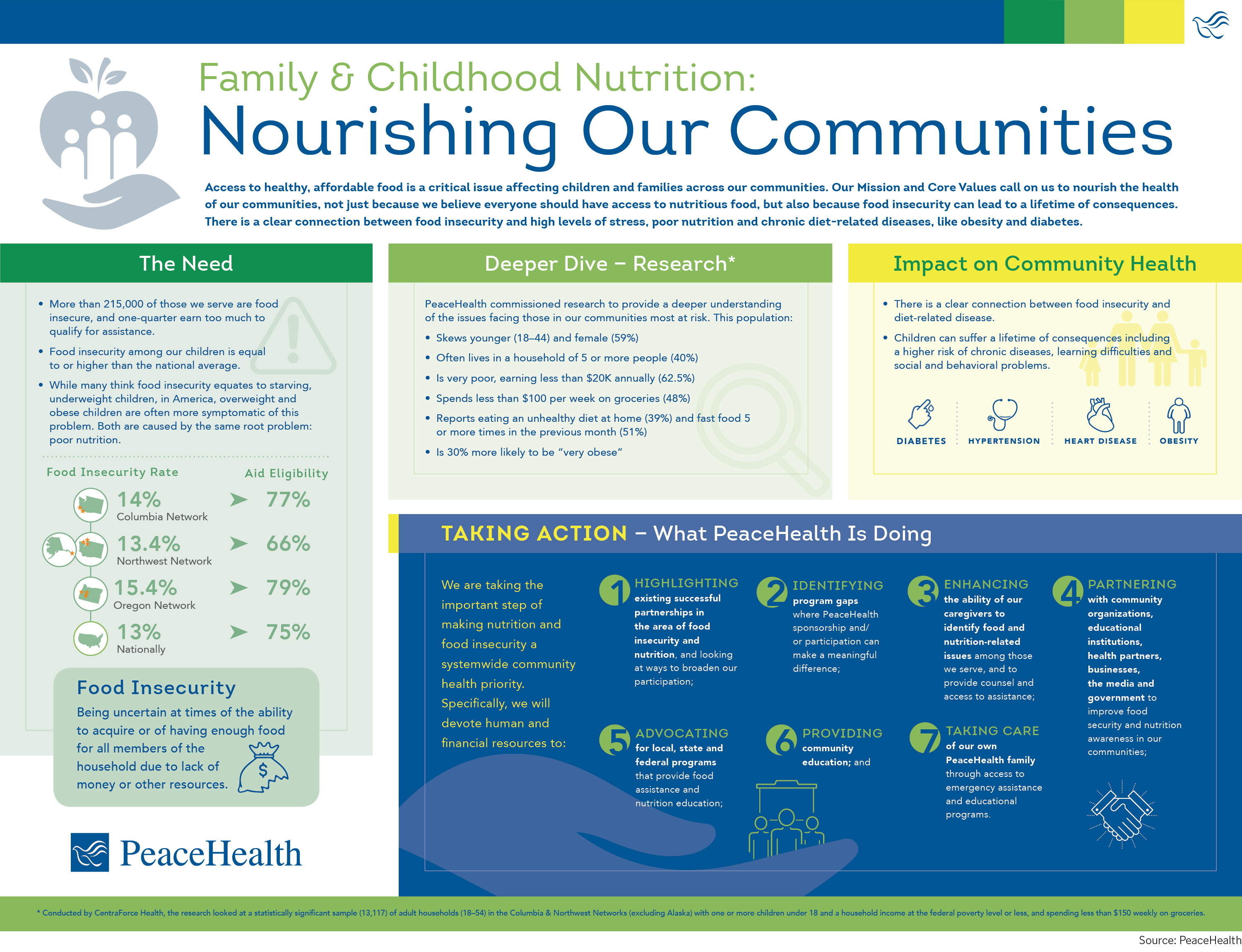

PeaceHealth's service area includes Washington, Oregon and Alaska. According to the U.S. Economic Research Service report on food security for 2015-2017, food insecurity in Oregon and Alaska were in line with U.S. averages while Washington state fared better than the U.S. average. But PeaceHealth found that areas served by its three networks or divisions have food insecurity rates that are higher than the national average of about 12 percent. Most impacted families have single women as head of the household.

The 2016-2019 community health needs assessment by PeaceHealth Southwest Medical Center in Vancouver, Wash., identified food insecurity among children as a major concern. In 2016, more than one in five children in the hospital's service area were food insecure, according to the report. The hospital funds community programs that provide healthy meals for children, nutritional education for parents, cooking classes for kids and adults and school-based gardening programs to increase the consumption of fruits and vegetables.

Undernourished and overweight

McCarthy said Americans expect malnourished children and adults to be underweight, but the food insecure can be overweight or even obese. According to the nonprofit Food Research & Action Center, "food insecurity and obesity can be independent consequences of low income and the resulting lack of access to enough nutritious food or stresses of poverty." Low-income families and individuals may live in neighborhoods where there is easy access to fast food franchises but no full-service grocery. Produce, if available, may be higher cost and lower quality.

"Nourishment is not just about calories," McCarthy said, "So we have to totally shift our thinking in health care" to recognize and combat food insecurity. To that end, PeaceHealth has made improving nutrition and tackling food insecurity a systemwide priority.

Health care providers have a role to play in identifying individuals and families facing food insecurity and in linking them to community resources and assistance. McCarthy said that clinicians can open the way to "better conversations" about the relationship between diet and health and identify food insecurity by asking patients to answer yes or no to the following statements:

- "Within the past 12 months, we worried whether our food would run out before we had money to buy more."

- "Within the past 12 months, the food we bought just didn't last and we didn't have money to get more."

Two federally funded programs — the nonprofit Meals on Wheels and the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children — have been around for decades and have helped reduce hunger and malnutrition, McCarthy said. But those programs don't cast a wide enough net.

Cecelia Jacobson, a PeaceHealth registered dietitian, stirs salad greens on the opening day of an organic farm stand on the campus of PeaceHealth Sacred Heart Medical Center at RiverBend in Springfield, Ore.

PeaceHealth's current efforts to combat malnutrition include veggie voucher programs and food pharmacy programs in its service areas. The system is addressing the root causes of food insecurity by supporting community programs that increase access to healthy foods for children and families and through its initiatives to improve the economic and health status of low-income families.

All hands on deck

To make more progress against malnutrition, McCarthy said PeaceHealth wants an all-hands-on deck approach to frame the issue as a community priority and find solutions at the community level.

"We really need more activists," she said. "We all make hundreds of decisions every day about food. We are immersed in it. Our communities are based on who we break bread with. When we learn for ourselves and provide that knowledge to our families and our neighbors and our churches, then we really have made an impact on our communities."

PeaceHealth's effort to nourish communities follows a seven-step plan (see graphic below) and includes highlighting existing successful partnerships, identifying gaps, encouraging caregivers to give nutrition advice, working with community organizations, advocating for government programs and providing community education.

The final step, McCarthy said, is making sure to care for PeaceHealth staff members themselves, giving them access to emergency assistance and educational programs to improve their own nutrition. That effort, she added, has a booster in the system's president and chief executive, Liz Dunne, who is a registered dietitian.

"This comes from a fundamental belief in the power of food," McCarthy said. "At a core level, senior leadership allowed us to be really innovative. I don't know of any other CEO who brings that emphasis, so we have the opportunity to bring attention to making this one of our core values."

Making healthy eating a positive value at PeaceHealth can have a multiplier effect, she said. "In health care, we are not always great about walking our talk, but we realized that the most direct way to improve the health of our communities, where many times we are the largest employer, is to start with ourselves."