By MARGARET GILLERMAN

Abuse of a 4-year-old child in Hot Springs, Ark., by her mother and the woman's boyfriend was so severe that the girl's story last year drew international attention.

The child told police her name was "idiot" because that's what her mother's boyfriend called her. He had repeatedly tied her wrists to a bed with tight constraints and beaten her with a plastic bat.

A child pauses in the healing garden at the Cooper-Anthony Mercy Child Advocacy Center in Hot Springs, Ark.

Scars and bruises marked the 4-year-old's face, back and wrists and she had dried blood on her face when authorities first saw her. Emotional scars had left her fearful and isolated.

"He broke the rainbow," the girl later told therapists when scribbling over a purple rainbow she had colored.

A little more than a year after police arrested her abusers, the girl is mending, thanks in part to the compassionate care she receives at the Cooper-Anthony Mercy Child Advocacy Center in Hot Springs, an outreach ministry of the Chesterfield, Mo.-based Mercy health system. Mercy funds the program along with state aid and private grants.

The child's assailants are both in prison after sentencing early this year. Both pleaded guilty to domestic battery and endangering the welfare of a child. The girl, who is in the state's foster care system, receives weekly trauma therapy at the Cooper-Anthony center.

Her foster mother and father are in the process of adopting her. Her foster father is the biological father of some of her half-siblings and she has been living in a house full of children, some of whom are her half-siblings.

Dickerson

"This family is so awesome and excited about the adoption," said Julie Dickerson, the girl's therapist at Cooper-Anthony. "The foster parents are sent from Heaven."

Dickerson said that after more than a year of therapy, the child is just now to that place in therapy where she can talk about the abuse she endured. However, she is showing signs of resilience, and even joy. She skips and plays in the center's garden. She voices affirmations she hears from Dickerson. "She says, 'I'm not ugly. I am beautiful.' … She says, 'I am not an idiot,'" Dickerson said.

Trauma-focused response

When a child walks through the door at Cooper-Anthony, he or she is greeted by an advocate who will assist the child and family with any questions or resources they may need. If an abuser is prosecuted, the advocate sometimes accompanies the family to court as support.

Law enforcement investigators, medical providers, child advocates and mental health counselors come together at the center, so the abuse victim is spared the stress of having to go to an emergency room, police stations and other unfamiliar locations. The sensitive, centralized approach reduces the risk of further traumatizing the child, said Karen Wright, a licensed professional counselor who directs the center.

"It's best practice for children," she said.

Wright

A forensic interviewer conducts an initial recorded interview with a child victim in a quiet room with only the child and interviewer present, Wright said. Law enforcement investigators and a representative of Children and Family Services watch on a television monitor in an observation room and may feed additional questions to the interviewer.

Specially trained nursing staff are available to conduct sexual assault examinations, if warranted, to gather evidence for potential prosecution of an abuser. (The majority of the 600 children from infants to age 18 who come to Cooper-Anthony each year have been sexually abused, sometimes over long periods.)

The multidisciplinary team conducting the abuse investigation "may uncover evidence of environmental neglect, pornography, physical abuse, domestic abuse and sexual abuse," said Wright. "If there's one of these, there are most likely others."

Emotional healing

The center's therapists provide ongoing trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy to help abused children heal emotionally and spiritually. The nonprofit's services are free of charge.

Therapy can continue for a year or more in severe cases, and children may return for follow-up care as they mature and comprehend more about the nature of their abuse.

"What we're trying to do is educate the family so the children won't be in counseling forever," said Dickerson, who is a licensed professional counselor. "We want parents to know how to deal with trauma symptoms so they can show the children how to cope." The parents are part of the therapeutic process and receive assignments to practice at home.

Handprints of some of the children who have been helped by the Cooper-Anthony Mercy Child Advocacy Center decorate a poster at the Hot Springs, Ark., facility.

The girl's story

The girl was brought to Cooper-Anthony for services after a call to the Arkansas State Crimes Against Children Hotline.

"She was very negative about herself and did not come out of her shell," Dickerson said. Without therapy, the child's feelings could have hardened into a permanent sense of low self-worth. "Those things get ingrained, especially in toddler years," she said.

Therapists address children's thought distortions — or "stinking thinking" — that may cause them to think they should be ashamed. A child's shame "melts away when they finally let go of mistaken beliefs," Dickerson said. In therapy sessions, young victims learn words to describe their abuse. They come to know the abuse was not their fault. Children are taught coping and de-stressing skills to use when they are exposed to emotional triggers.

The unspeakable

A critical tool in recovery is a trauma narration, where the child tells his or her story, in order to make the emotions manageable and diminish pain.

"We want to reach a point where the children can speak the unspeakable," said Dickerson.

Young children may draw pictures or use puppets to tell their stories. Older children often will write down their stories. Some make picture books or timelines.

The 4-year-old girl, now 5, took almost a year to feel safe and emotionally ready to begin her narration, although bits and pieces had come out in therapy. The girl began her therapy with Wright, and she told Wright her mother's boyfriend had "spit on me and scared me" and hurt her hands when she knocked on the door.

Now she uses a dollhouse and figures for "play talking" her narration, which she will tell to her foster parents as part of the therapy protocol. She no longer refers to her abusive birth mother as mother. She puts that doll in jail.

"She said her birth mother called her names and put her in a kennel," Dickerson said.

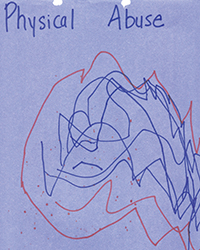

This therapy drawing is one of the first made by the 4-year-old girl abused by her mother and mother's boyfriend. The child was asked to draw a picture about her abuse. A caregiver wrote the descriptor atop the drawing.

The girl calls another doll representing her foster mother "Mama."

When the trauma narration is completed, on paper or in some other form, the child is encouraged to destroy it and say "this is part of my past."

"It's very symbolic and very tangible," Wright said.

Wright said one goal of therapy is for the child to know: "Abuse is something that happened to them, but it's not their identity."

Spiritual counsel

Wright said that spiritual healing is an important component of care at Cooper-Anthony. She told the story of a boy who was sexually abused from ages 5 through 8 and disclosed his abuse at age 9. His family brought him to Cooper-Anthony after he became suicidal.

One day the boy learned that his abuser, a teenage family member, would not be prosecuted. He climbed up a tree in the center's garden and refused to come down.

"He said, 'why did God do this to me? Nobody believes me,'" Wright said. Wright told him: "'God didn't do this … God loves you. Evil happens, but God ultimately wins."

After more than four years of counseling, the boy, now a young teen, still returns to the center for check-ins.

The boy's mother told Mercy's Jennifer Cook, senior media relations specialist who writes for Mercy, that the Cooper-Anthony's staff "made him feel respected … like he mattered." The mother told Cook: "They supported him when he felt like everyone had given up on him. They are true, actual superheroes because they change lives every day."

Copyright © 2017 by the Catholic Health Association

of the United States

For reprint permission, contact Betty Crosby or call (314) 253-3490.