By BETSY TAYLOR

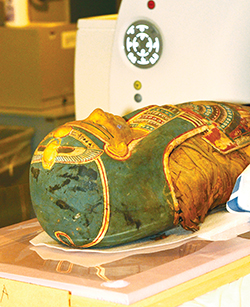

Forensic anthropologist Robert Pickering, left, and CT technicians Lynn Hightower and Kelly Coffelt prepare to scan a Roman-era mummy at SSM Health St. Anthony Shawnee Hospital on Aug. 20 to gather images for analysis about the mummy's past.

A hospital and museum in Shawnee, Okla., teamed up to take images of two ancient mummies using a 64-slice CT scanner this summer. The mummies arrived at the emergency room at SSM Health's

St. Anthony Shawnee with a protective police escort. They got their images without delay, and now doctors and scholars are studying the scans to solve some of the mummies' mysteries.

"There's a lot you can find out about a person from her bones," said Delaynna Trim, curator of collections for the Mabee-Gerrer Art Museum. The museum, an encyclopedic art museum with holdings from ancient Egypt to modern times, houses the two mummies.

One is an Egyptian mummy known as Tutu, who lived about 2,400 years ago; the other is nameless and commonly called the Roman-era mummy, from a time about 2,000 years ago when Egypt was part of the Roman Empire. Ancient Egyptians embalmed and wrapped a body to preserve it before burial. They mummified their dead because they believed the physical body was important in the afterlife.

A businessman from Buffalo, N.Y., brought Tutu — then called Princess Menne — to the U.S. in the late 1800s, transferring the mummy to a museum in 1898. When that museum closed in the 1920s, the Mabee-Gerrer Art Museum acquired the mummy. Emily Teeter of the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago translated hieroglyphs on the mummy's breastplate in 1992 and realized the mummy's name was actually Tutu. The museum acquired its Roman-era mummy around the same time as Tutu, but less is known about that mummy's pedigree or history.

Inside story

Tutu was X-rayed in 1963. CT scans were taken of Tutu in 1991 and of the Roman-era mummy in 1992. However, those images don't offer the level of clarity now possible. After St. Anthony Shawnee installed its 64-slice CT scanner in March, the director of the Mabee-Gerrer Museum of Art, Dane Pollei, asked Charles "Chuck" Skillings, the hospital's president, about taking new images of the mummies since they hadn't been examined in about a quarter century.

It took about three months of planning, beginning in May, to coordinate the mummies' visit for the scans. A fine art business built custom cases to protect the mummies and to hold them steady during the imaging. A trial run transporting just the cases on gurneys was held the day before, to practice navigating through doorways and down halls, Trim said.

Respect for the dead

The Mabee-Gerrer museum is on the grounds of St. Gregory's University and St. Gregory's Abbey, and the mummies are part of the abbey's holdings. Abbot Lawrence Stasyszen, OSB, the university's chancellor and head of St. Gregory's Abbey, blessed the mummies before they left the museum for the hospital. Abbot Stasyszen said his blessing included a remembrance of Khaled al-Asaad, a renowned Syrian archeologist who had recently been killed by ISIS militants for refusing to disclose the location of valuable artifacts from ancient Palmyra, and others who pursue knowledge of ancient cultures. Abbot Stasyszen and Trim said the museum and those involved in the transport and imaging remained mindful that they were handling human remains and were respectful of that.

The police escort was arranged to reduce any possibility of a vehicle accident that could damage the mummies, said Carla Tollett, a hospital spokesperson who helped with the planning for the mummies' early morning hospital visit. She said no patients were inconvenienced by the mummies' scans.

An Egyptian mummy, Tutu, from the Mabee-Gerrer Museum of Art in Shawnee, Okla., is in position for a CT scan at SSM St. Anthony Shawnee.

Dr. Ryan Skinner is a radiologist with the Oklahoma Radiology Group, who works at the radiology department at St. Anthony Shawnee. He said about 2,700 images were taken for each mummy and combined into detailed body maps. The CT scan uses X-rays to capture images as precise anatomical slices.

In a patient, the CT scan is used to produce three-dimensional views of soft tissue, bones and blood vessels to assist with medical diagnosis. Those who have studied the Mabee-Gerrer mummies' scans say that time and decay disintegrated soft tissue, connective tissue, blood vessels and nerves.

In addition to Teeter and Skinner, the museum's curators are working with Robert Pickering, a forensic anthropologist at the University of Tulsa; Jonathan Elias, director of the Akhmim Mummy Studies Consortium in Pennsylvania; and Carter Lupton, a curator at the Milwaukee Public Museum, to analyze the scans and research the mummies, said Pollei.

On Oct. 23, some preliminary results about Tutu were shared at an event with museum members, based on the work of the museum, Pickering, Elias, Skinner and other radiologists at St. Anthony Shawnee. Their findings confirm Tutu was a woman who possibly died in her 50s, which is quite old for the time in which she lived. She had given birth to at least one child. She had a sandy, chalky substance applied to her shoulder and two dense objects inside her body near the same shoulder. It's possible these were intended to cure her of an ailment in the afterlife that she'd had while she was alive. She had organs mummified and placed back inside her body.

The researchers also have confirmed that the Roman-era mummy was an adult female.

As researchers previously have noted, Tutu's brain was removed through the nose, a common practice during mummification, and Tutu's arms are crossed. A mummy wrapped with crossed arms indicated the person was of high status in society.

Skinner said both mummies have pelvic fractures, and Tutu has several abnormalities of the spine, including dislocation and fractures that shortened the mummy's torso. He said most "but not exactly all" of the fractures happened after Tutu's death.

Researchers previously thought the Roman-era mummy's brain was not removed during mummification, and they'll continue to study the latest scans to learn more. Pollei said much of the Egyptian culture disappeared after Egypt became a province of Rome, and the mummification process wasn't as sophisticated at the time of the Roman-era mummy, which is one reason researchers believe the Roman-era mummy's brain wasn't removed.

Skinner — who notes he's not an expert on ancient Egypt and that he's just discussing initial observations — said it's possible there's resin in the cranial vault, which could have been used as a preservative in the mummification process, but he doesn't see the remnants of previously normal brain tissue. He can't see anything that shows the Roman-era mummy's brain was removed, but he also doesn't see anything indicating how resin might have been placed in the cranial vault.

Following in the mummies' footsteps

Trim said St. Anthony Shawnee donated the mummy scans. She said the museum may pursue grant funds to draw from the detailed images to create a facial reconstruction that would model what the mummies looked like. The museum, which displays previous scans taken of the mummies, will add the new scans as part of its ongoing work "to teach about these people and their lives," she said. The new images also will be added to a scientific database of Egyptian mummies to increase knowledge of ancient Egypt and its culture, Pollei said.

In addition to drawing attention to the mummies, the experience has also raised the profile of the hospital's diagnostic equipment. Tollett, the hospital spokesperson, said staff report it's not uncommon for patients to now ask: "If I get a CT scan, can I get the one the mummies were in?"

Copyright © 2015 by the Catholic Health Association of the United States

For reprint permission, contact Betty Crosby or call (314) 253-3477.