BY: SR. KATHLEEN POPKO, SP, PhD

The ministry of advocacy has been an integral part of Catholic health care, beginning with the pioneering women religious who both cared for those in need and advocated for their health and welfare, as well as for the organizational structures to help them.

How the Catholic health ministry carries out this function of advocacy has evolved significantly in its sophistication, complexity, scope and reach across local, state and national levels.

At this time of major health care reform, Catholic health care once again needs to adapt and expand its advocacy focus as the clinical care delivery system broadens beyond sick care to address disease prevention and promotion of population health. There is a new emphasis on coordinated community benefit assessments and responses, as well as closer attention to the underlying social and environmental determinants of health.

These changes carry significant implications for Catholic health care's advocacy agenda and the strategies required to carry it out.

CHANGING LANDSCAPE

In response to a variety of public policy and economic pressures, health care providers are expanding their horizons to engage more deeply with patients and with the communities they serve. Health delivery reform is driving changes as clinical providers become more clearly accountable for following the care of patients after they return home. Penalties for readmission within 30 days, or the economic consequences of risk-based contracts, are influencing providers' behavior to an increasing degree.

Prompted by the development of accountable care organizations, clinically integrated networks and global payment mechanisms, emphasis on population health management is expanding the health providers' arena to include the health needs of defined portions of the population.

Going beyond this relatively narrow population management focus, total population approaches aim at improving the health of an entire population. The result: Health care systems are being moved into the public health realm. Clinical providers find themselves urged to address environmental and social determinants of health — such as food and nutrition insecurities, air pollution, water and soil contamination, housing and safety — and to develop collaborative strategic responses.

Simultaneously, the public health sector, which traditionally addressed communicable diseases, risky behaviors and mortality, is broadening its scope to address social inequities, living conditions and institutional power.1 This approach includes engaging with the entities within the civic community that can impact health, have influence and help change take place. A recent National Association of County and City Health Officials publication goes further, encouraging health departments "to expand the boundaries of their practice to use their resources, perspectives and alliances to more directly confront the social inequalities that are the roots of health inequities."2

MORECOMPLEXITY

The very words used to talk about these changes add to the complexity. There is a lack of clarity around the various terms being used to discuss health in general and, specifically, about population health and the interrelated systems needed to sustain the health of individuals and communities. The language, which is undergoing evolution and refinement, can be confusing.

A comprehensive study by Dawn Marie Jacobson, MD, MPH, and Steven Teutsch, MD, MPH, provides a set of integrated definitions as well as an environmental scan of current efforts to measure and improve the health of total populations.4 Their research confirms that multiple factors influence the health of individuals over the course of a life. These researchers point to the need for "population-based strategies to address the ‘upstream' determinants of health, which parallel individual prevention-focused behavioral change strategies to improve health and prevent disease.5

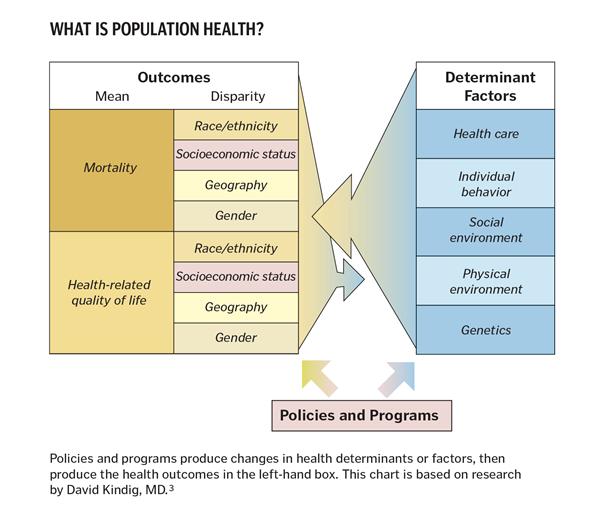

In one current categorization, the determinants of health are (see chart):

- Health care

- Individual behavior

- Social environment

- Physical environment

- Genetics

Jacobson and Teutsch maintain that these determinants should be used by all organizations interested in improving total population health.6

Two other aspects are key. David Kindig, MD, who created the chart above, adds that "These circumstances (social determinants of health) are in turn shaped by a wider set of forces: economic, social policies and politics."7 Further, Jacobson and Teutsch stress the necessity for "'shared responsibility' for implementing these (population-based) strategies through multi-sectoral partnerships and collaborations…"8

In short, a combination of factors is coming together in this time of transition:

- The necessity to look "upstream" to gain a deeper understanding of the social and environmental factors determining health of populations

- The importance of attending to the economic, social and political policies impacting the health of populations

- The need to shape an advocacy agenda in collaboration with other stakeholders to gain the leverage required to affect public policy.

IMPACT ON THE ADVOCACY AGENDA

Health care's changing paradigm is broadening clinical providers' approaches to health delivery, as well as their understanding of their communities' needs. The changing paradigm has implications for advocacy agendas as providers explore the root causes of health problems of the populations they serve.

Over the past 25 years, Catholic health care providers' assessment of community health needs has been guided by the Catholic Health Association's seminal work on the topic, as well as by state and federal requirements related to community needs assessments and documentation of community benefit.

In the article "Assessing and Evaluating Community Benefit," Pamela Schaeffer, PhD, described CHA's year-long study in 1988 in which Catholic health providers had to determine whether, or to what extent, they were benefiting the entire community.9 The resulting report, published in 1989, provided the foundation for CHA's social accountability budget. It was followed in 1992 by development of its standards for community benefit.

CHA coupled these initiatives with urging its members to strengthen their advocacy efforts on behalf of universal health care, maintenance of nonprofit health care organizations' tax exempt status and assistance for the uninsured. The standards themselves called for health care organizations to "take a leadership role in advocating community-wide responses to health care needs in the community."10

The Catholic health care ministry responded to this challenge and is continuing to do so. For example, in its plans for 2015, Trinity Health asks its regional health ministries not only to complete their usual community needs assessment, inventory and plans for community benefit programs, but also "to integrate care for our communities by addressing the social determinants of health." As follow-up actions, the health system has asked the regional health ministries to convene work groups of community partners and stakeholders for addressing key needs and responses. In Michigan, Mercy Health Muskegon has used a Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation grant to develop a pilot program with a hub-and-spoke structure to facilitate this type of dialogue and action.11 Such innovative community benefit initiatives naturally begin to shape an organization's individual and collective advocacy agendas. As stakeholders — such as clinical care providers, public health agencies and community service organizations and others — address population health and its environmental and social determinants, their findings undoubtedly will point to the need for coordinated advocacy strategies.

In a 2014 Health Progress article, Daniel DiLeo provided a useful example when he commented, "Because environmental concerns can affect population health — air pollution can trigger asthmas, for example, or a chemical spill can make it unsafe to drink from a town's water supply — the ministry can look for and act on opportunities to make significant environmental advocacy contributions."12

This is not to say that Catholic health providers will lessen their traditional advocacy work, such as enhancing Medicare and Medicaid; implementing the Affordable Care Act; addressing reimbursement and quality regulations; and so on. Nor does it mean weakening their support for CHA's national advocacy in favor of, for example, health care reform, funding of the Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP), ethics and conscience clause protections, policies on euthanasia and other issues.

What it does imply is that Catholic health care providers will need to move "upstream" to attend to the root causes of health problems, to expose the underlying issues of violence, pollution, inadequate food, poor housing and other social disparities associated with poor health. In understanding these underlying social and environmental determinants, Catholic health care providers will be called upon to collaborate with others both to develop effective programs and also to advocate for and help shape public policies that can impact the health of the population. As findings and learnings emerge, Catholic health care providers can take advantage of their collective size, scope and national breadth to influence public policies, urge needed research and demonstrate effective approaches.

NEW ATTITUDES

This type of change requires shifts in perception and attitudes among all Catholic ministry leaders, especially as they focus on exploring, understanding and addressing the underlying causes of poor health in their communities. Health care must move beyond the sick-care system to promote living environments that foster good health and to develop coordinated approaches for the prevention of disease and illness at both the personal and community levels.

Catholic health providers already have developed and put in place community benefits processes to help build partnerships and coalitions and to take the advocacy actions needed, whether locally, regionally or nationally. As Kevin Barnett of the Public Health Institute, based in Oakland, Calif., comments, "Hospitals can …. use their considerable political power to coordinate with public health leaders and partners to advocate for health in transportation, housing, agriculture and other policies that have been shown to have an impact on health outcomes."13

EXPAND AGENDAS

In summary, Catholic health care providers are being called to expand their advocacy agendas

14 in the midst of unprecedented change:

- Moving from uncoordinated and often random attempts at addressing community health to strategic thinking that engages the community in defining the issues

- Extending beyond the provision of clinical or sick care to addressing the "upstream" social and environmental determinants of health

- Evolving from singular attempts to collaborative partnerships and coordinated advocacy to strengthen their impact in shaping programs and public policies

- Developing successful local activities to regional, national and even global initiatives that advocate for environmental justice, disaster preparedness, responses to climate change impact (drought, fire, floods) and the sustainability and health of Earth.

This expanding of the advocacy agenda is very consistent with the mission of the Catholic health care ministry. It seems clear that Catholic health care's collective advocacy for the health of populations, for healthy living environments and, indeed, for a healthy planet, should be an essential part of the future.

SR. KATHLEEN POPKO, SP, is president of the Sisters of Providence, Holyoke, Mass.; a board member of Trinity Health, Livonia, Mich.; and, previously, was a member of the Catholic Health East senior management team for 12 years.

NOTES

- Sandi Galvez, "A Public Health Framework for Reducing Health Inequities," Bay Area Regional Health Inequities Initiative, (PowerPoint presentation, 2014). www.phi.org/resources/?resource=barhii-social-determinants-framework.

- National Association of County and City Health Officials, Expanding the Boundaries: Health Equity and Public Health Practice (Washington, D.C.: NACCHO, 2014), 1.

- David Kindig, "What Is Population Health?" Improving Population Health blog, www.improving population health.org/blog/what is population health (accessed Dec. 26, 2014).

This model was adapted from the original Evans and Stoddart field model and expands on Kindig and Stoddart. See Robert G. Evans and Gregory L. Stoddart, "Producing Health, Consuming Health Care," Social Science and Medicine 31, no. 12 (1990) 1347-63, and David Kindig and Gregory L. Stoddart, "What Is Population Health?" American Journal of Public Health 93, no. 3 (March 2003): 380-383. - Dawn Marie Jacobson and Steven Teutsch, An Environmental Scan of Integrated Approaches for Defining and Measuring Total Population Health by the Clinical Care System, the Government Public Health System and Stakeholder Organizations, commissioned paper (April, 2012): 2. www.improvingpopulationhealth.org/PopHealthPhaseIICommissionedPaper.pdf (accessed Dec. 26, 2014).

- Jacobson and Teutsch, 2.

- Jacobson and Teutsch, 2.

- Kindig, 2.

- Jacobson and Teutsch, 2.

- Pamela Schaeffer, "Assessing and Evaluating Community Benefit," Health Progress 95, no. 6 (November–December 2014): 56.

- Pamela Schaeffer, "Standards for Community Benefit," Health Progress 95, no. 6 (November–December 2014): 59.

- Trinity Health, unpublished documents, CMMI grant: "Michigan Pathways to Better Health," Pathways HUB Model piloted at Mercy Health Muskegon, Muskegon, Mich.

- Daniel DiLeo, "Care for Persons, Care for Planet," Health Progress 95, no. 5, (September–October 2014): 36.

- Kevin Barnett and Martha Somerville, "New Hospital Community Benefit Briefs: Reporting and Requirements and Community Building," New Public Health, www.rwjf.org/en/blogs/new-public-health/2012/10/new_hospital_communi.html (accessed Dec. 26, 2014).

- Adapted and expanded from Julie Trocchio, "Community Benefit and Population Health: From Legacy to Leadership" (presentation at the Catholic Health Association's pre-LCWR assembly sponsorship conference, Nashville, Tenn., Aug. 12, 2014).