BY: KATHERINE M. PIDERMAN, Ph.D.; CHRISTINE M. SPAMPINATO; SARAH M. JENKINS, M.S.;

FR. DEAN V. MAREK; FR. JAMES F. BURYSKA, STL; MARY E. JOHNSON, M.A.; FR. JOHN L. EVANS;

FR. JOSEPH P. CHACKO, M.A.; DAVID J. PLEVAK, MD; and PAUL S. MUELLER, MD

In a constrained economic environment, every facet of the health care team must function with the highest efficiency, including those who provide pastoral care. To function efficiently and effectively, both the needs and the expectations of patients need to be considered. This paper highlights the specific spiritual needs and expectations of Catholic inpatients and proposes a model for chaplains to optimally assess and provide care for them.

There is a growing body of evidence indicating that tending to the spiritual needs of patients contributes to their well-being and healing.1 These results and the results of our study provide a mandate to hospitals committed to the holistic health of patients to provide the appropriately educated and trained personnel needed to assess and respond to spiritual needs. Such a commitment, especially in the midst of financial challenges, will breathe life into mission statements and promote the Gospel.

BACKGROUND

The role of spirituality in promoting health and well-being has been widely researched.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 In many hospitals, chaplains are respected members of the health care team and often are charged with assessing and tending to the essential spiritual needs and expectations of patients.3, 6 Unfortunately, prior research indicates that the spiritual needs and expectations of many patients are not adequately met.3, 5

This is a financially challenging time for health care institutions, making it imperative that hospital chaplains join others in understanding ways that they can practice good stewardship while providing important spiritual care to those who need it. In order to broaden our understanding of the spiritual needs and expectations of hospitalized inpatients and to predict which patients are most likely to want to be visited by a chaplain, we conducted a survey of 4,500 discharged inpatients, 1,500 from each of the three Mayo Clinic sites (Rochester, Minn., in 2006, Phoenix, Ariz., in 2008 and Jacksonville, Fla., in 2009). The overall response rate to our survey was 35 percent. Approximately one half of the respondents were men (764; 51.0 percent). The majority were married (1,187; 75.7 percent), age 56 years or older (1,221; 77.3 percent), and reported an affiliation with Catholic or Protestant denominations (1,292; 81.2 percent).

We found that though 69.5 percent of our respondents would have liked at least one visit from a chaplain during their hospitalization, only 43.5 percent were visited. In addition, 39 percent of patients also expected a chaplain to visit them without their request. We also discovered that

40 percent of respondents lacked awareness of the availability of chaplains to minister to them, and 62.4 percent did not know how to contact them.

Using a predictive modeling statistical procedure (multivariate logistic regression), we identified the characteristics of patients who were most likely to want a chaplain's ministry. The strongest predictor of wanting a chaplain to visit was a reported affiliation with Catholic or Protestant denominations. Catholic patients were almost 8 times as likely to want to see a chaplain and Protestants were more than 4 times as likely, when compared with those who did not report an affiliation with either Catholic or Protestant denominations (Catholic: OR = 7.97; p < .001; Protestants: ORs = 4.96 and 4.29 for Evangelical and Mainline, respectively; p < .001 for each). Being female was the only other significant predictor of wanting a chaplain's ministry, with female patients being 1.5 times more likely than male patients to want this service (OR = 1.52; p = 0.02).

Surprisingly, several other variables, including age, marital status, emergency admission, time in an intensive care unit, or duration of stay were not predictive of wanting chaplain visitation. These results were published in 2010.7

COMPARISONS OF CATHOLIC PATIENTS WITH OTHERS

Our 2010 findings served as a catalyst to explore how we might respond to the sobering gap between patients' expectations and chaplain visitation. We began by further analysis to try to understand how we might better serve our Catholic patients. We targeted the Catholic patient subgroup first, since they were almost twice as likely to desire visitation as any other subgroup. (However, we are committed to providing subgroup analyses of other patients at a later time.) Our review of data indicated that 81.5 percent of Catholic respondents wanted to be visited by a chaplain during their hospitalization, compared to 73.7 percent of Protestants and 41.1 percent of Others (χ2 = 147.0, p < 0.0001). Catholics were also more likely to indicate a desire to be visited on a daily basis (Catholics - 27.3 percent, Protestants - 16.6 percent, Others - 10.0 percent, χ2 = 36.8, p <0.0001). For these analyses, we assumed that a blank response indicated ‘no visit desired.' Additionally, Catholic patients also endorsed their appreciation for the visits they did receive as "very important" more often than other patient groups (Catholics – 63.6 percent, Protestants – 46.6 percent, Others 28 percent, χ2 = 37.2, p < 0.0001).

Catholic patients, like other patients, look to chaplains to remind them of God's care and presence, to pray and read religious texts with them and to offer support and guidance to them and to their loved ones.5, 8 However, Catholic patients were very different from other denominations in how they rated the importance of religious rituals or sacraments. As a reason for a chaplain visit, 82 percent of Catholics indicated that rituals and sacraments were important, as, compared to 35 percent of Protestants and 18 percent of others (χ2 = 294.3, p. < 0.0001). These data support an earlier study which indicates that Catholics of all ages value the sacraments as the most important connection to their faith.9

THE ROLE OF THE EUCHARISTIC MINISTER

One of the long-standing ways we have attempted to identify and triage the needs of Catholic patients hospitalized in the inpatient settings of Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., has been to address the desire of Catholic patients for Communion. Our administrative assistants make lists of newly admitted Catholic patients. A Eucharistic minister, who has been trained in relevant hospital policies, passed the required background check and has been ecclesiastically commissioned to administer Communion, visits patients self-identified as Catholic within 24 hours of admission. The Eucharistic minister asks each newly admitted Catholic patient about his/her desire for Communion. If the patient desires Communion while in the hospital, the Eucharistic minister prays with the patient and administers Communion. The Eucharistic minister also places a card near the patient's hospital room door to identify him or her to subsequent Eucharistic ministers. Finally, the patient's preference for receiving Communion is recorded and returned to the administrative assistants. Eucharistic ministers are not expected to address a patient's spiritual needs beyond administering Communion. However if a patient voices a desire for additional spiritual care, these requests are given to the administrative assistant, who then makes a referral to a chaplain.

THE ROLE OF THE CHAPLAIN

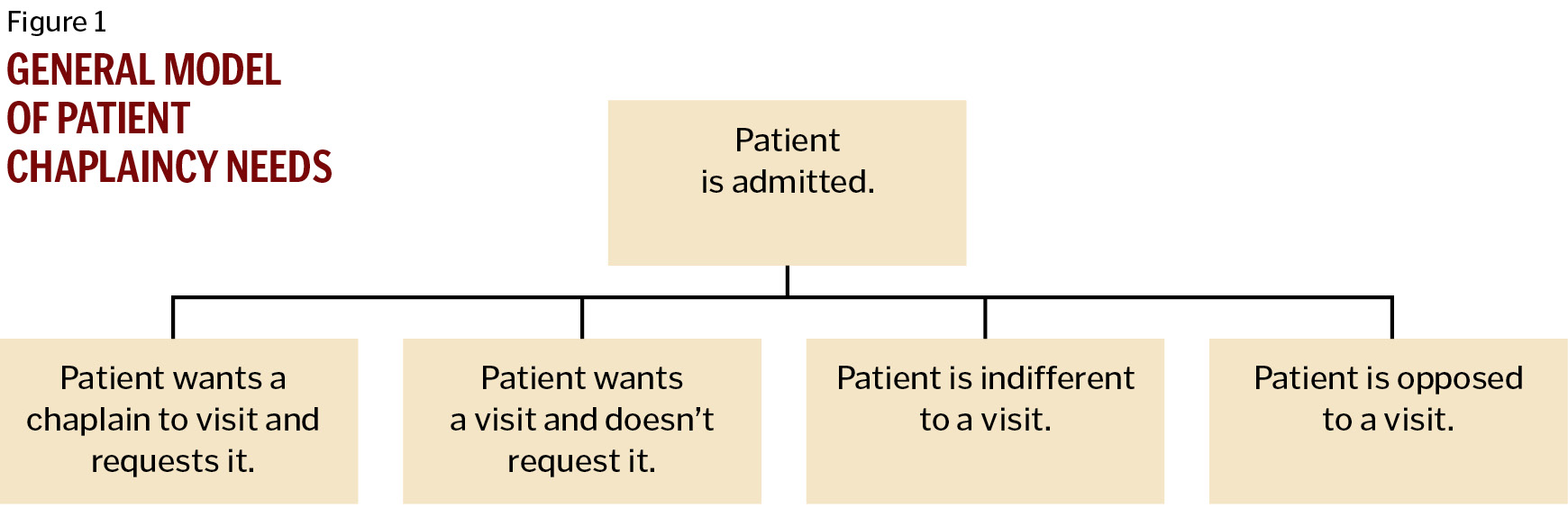

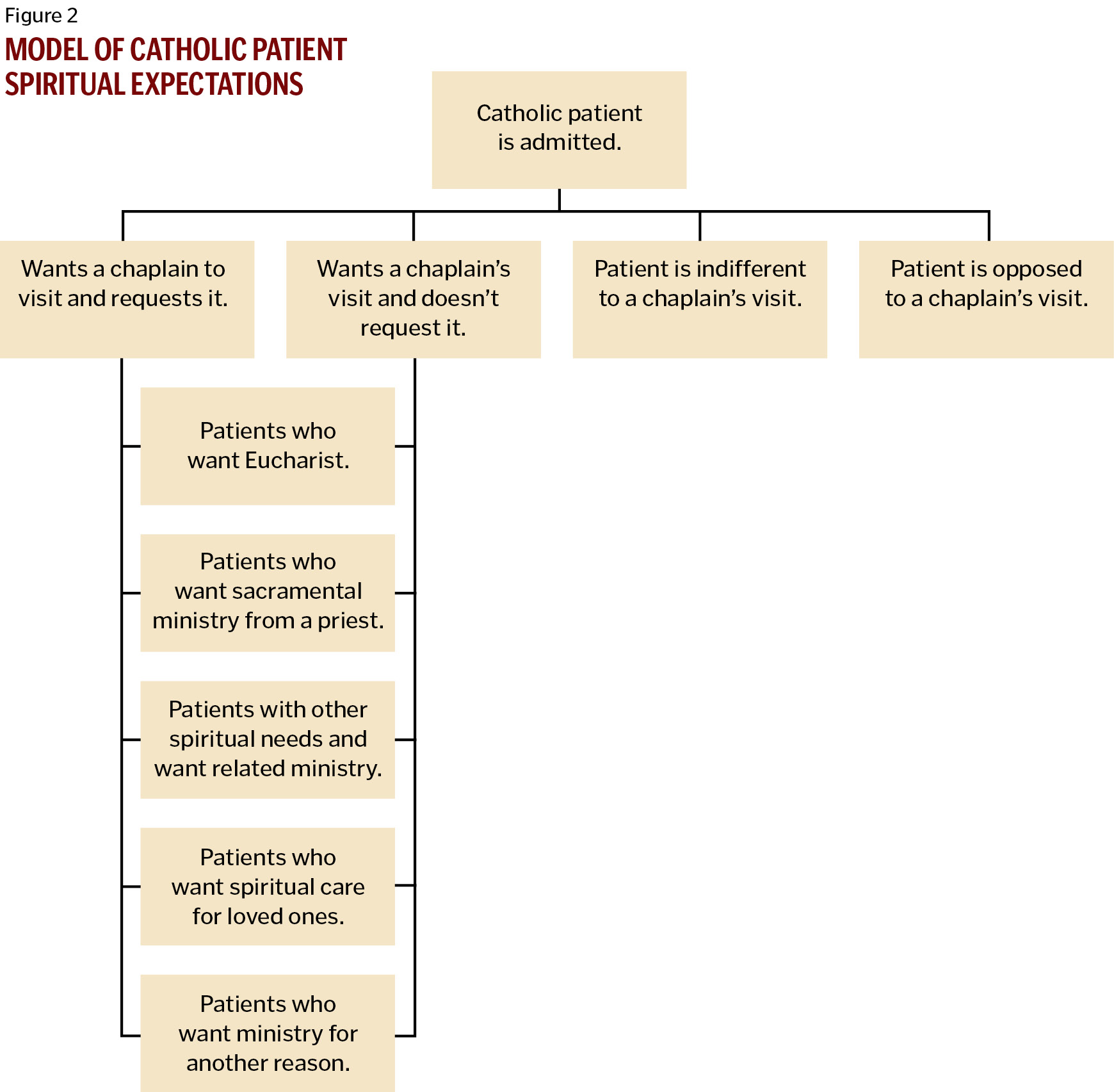

Although Eucharistic ministers make a very important contribution to caring for the spiritual needs of Catholic patients, more is needed. Ideally, each patient would be visited by a chaplain who has been theologically and clinically trained to assess and respond to the complex spiritual needs of hospitalized patients. Our ministerial experience indicates that patients can be thought of in four general subcategories: 1) those who want to be visited by a chaplain and make a request for visitation; 2) those who want to be visited by a chaplain and do not request visitation (for one or more reasons); 3) those who are indifferent to a visit by a chaplain; 4) those who do not want to be visited by a chaplain (Figure 1). Our ministerial experience also indicates that those who want to be visited by a chaplain present with a broad spectrum of spiritual needs, including: 1) those who want to receive Communion; 2) those who want to receive sacraments that only a priest can administer (e.g., the Sacrament of Reconciliation or the Sacrament of Anointing); 3) those who desire support or discussion related to spiritual distress and spiritual coping; 4) those who desire spiritual care for family members or friends; 5) those who want ministry for another reason (Figure 2). These disparate groupings point to the need for individual spiritual assessment, if possible, done at several time points during a patient's hospitalization.

Since visiting all Catholic patients several times during a hospitalization may not be a realistic goal, other interventions are important to consider. One important task would be to increase the awareness of chaplains' availability and the services they provide. In an effort to increase self-referrals by patients, new signage has been placed outside our chaplain offices and at several of our chapel locations about the availability of chaplains. We have also added contact information to a prayer book that is regularly distributed by chaplains. Additional efforts to increase the presentation of chaplain contact information include postings on the hospital's religious programming network. Future efforts will include an exploration of the efficacy of other available electronic media and computerized resources.

THE ROLE OF THE HEALTH CARE TEAM

Illness may diminish a patient's ability or energy to advocate for himself or herself, and it is important that those on the medical team are aware of the importance of advocating for them. Some research has emphasized that physicians and nurses may not fully understand the role of chaplains,3 and therefore may under-utilize chaplain services. Because of this, it is important that all staff receive education about spirituality and health research, information about common pastoral interventions and the availability of chaplains. One possible structure for this training at our institution could be a generalist-specialist structure10 in which the physician acts to triage all systems that could be contributing to a presenting condition, including a possible spiritual component. Once this need is identified, the physician would refer to the "spiritual specialist," the chaplain, who would then lay out a treatment for the patient. This increased physician partnership would hopefully contribute to meeting the spiritual needs of all patients, including Catholics.

CONTINUING QUALITY IMPROVEMENT

While chaplains have expressed a tension about trying to measure the work that they do for purposes of quality improvement, they remain committed to underscoring the importance of their ministry as part of the health care team.3 The results of our survey provide an important example of how research can contribute to improving spiritual care services and emphasizing their importance.7

In future studies, it is important that the term "chaplain visit" be clarified. As indicated in this article, it is a term that is often used in relation to the multiple spiritual care services chaplains provide, including various sacramental ministries, prayer and spiritual counseling for patients or their loved ones. But because some of these services are provided by Eucharistic ministers or other volunteers, there is a need to clearly define these services for accurate measurement, quality improvement and unambiguous reporting. Such clarity would provide clear and documented evidence of the spiritual care needs requested and the interventions provided. This article has identified an important spiritual need that seems particular to the Catholic patient — receiving the Eucharist and other sacraments. It will now be our task to attempt to address this need and expectation, while documenting the effectiveness of our service. Our Department of Chaplain Services hopes to continue to be proactive in promoting and providing such research in order to demonstrate the important outcomes of their work and outline ways to provide the highest quality of compassionate spiritual care.

KATHERINE M. PIDERMAN is coordinator of research, Department of Chaplain Services, and assistant professor of psychiatry, College of Medicine; CHRISTINE M. SPAMPINATO is a medical student, Mayo Medical School; SARAH M. JENKINS is statistician III, Department of Biomedical Statistics and Informatics; FR. JAMES F. BURYSKA, FR. JOHN L. EVANS and FR. JOSEPH P. CHACKO are staff chaplains, Department of Chaplain Services; FR. DEAN V. MAREK and MARY E. JOHNSON are retired from the Department of Chaplain Services; DAVID J. PLEVAK is a consultant in the Department of Anesthesiology and professor of anesthesiology, College of Medicine; and PAUL S. MUELLER is a consultant and division chair in the Department of General Internal Medicine and professor of medical ethics and medicine, College of Medicine; all at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

NOTES

- Harold G. Koening, Dana King, Verna B. Carson, eds. Handbook of Religion and Health ( New York: Oxford University Press, 2012).

- George Fitchett et al., "Physicians' Experience and Satisfaction with Chaplains: A National Survey," Archives of Internal Medicine 169 (2009): 1,808-1,810.

- Kathryn A. Lyndes et al., "Chaplains and Quality Improvement: Can We Make Our Case by Improving Our Care? Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy 15 (2008): 65-79.

- Paul S. Mueller, David J. Plevak and Teresa A. Rummans, "Religious Involvement, Spirituality, and Medicine: Implications for Clinical Practice, Mayo Clinic Proceedings 76 (2000): 1,225-1,235.

- Katherine M. Piderman et al., "Patients' Expectations of Hospital Chaplains," Mayo Clinic Proceedings 83 (2008): 58-65.

- Wendy Cadge, Jeremy Freese and Nicholas A. Christakis, "The Provision of Hospital Chaplaincy in the United States: A National Overview," Southern Medical Journal 101 (2008): 626-630.

- Katherine M. Piderman et al., "Predicting Patients' Expectations of Hospital Chaplains: A Multisite Survey," Mayo Clinic Proceedings 85 (2010): 1,002-1,010.

- Kevin J. Flannelly et al., "A National Survey of Hospital Directors' Views about the Importance of Various Chaplain Roles: Differences among Disciplines and Types of Hospitals," The Journal of Pastoral Care & Counseling: JPCC 60 (2006): 213-225.

- Dean R. Hoge, "Core and Periphery in American Catholic Identity," Journal of Contemporary Religion 17 (2002): 293-301.

- George Handzo and Harold G. Koenig, "Spiritual Care: Whose Job Is It Anyway?" Southern Medical Journal 97 (2004): 1,242-1,244.

Copyright © 2013 by the Catholic Health Association of the United States

For reprint permission, contact Betty Crosby or call (314) 253-3477.