Organizational ethics guides institutional decisions to align them with organizational values and is a fundamental component of institutional integrity. Although these principles dovetail closely with those in compliance, legal, human resources and other

areas, it is its own distinct area of work. However, since organizational ethics is still an emerging field, it is often unclear what it actually entails, especially in health care.

To help shed light on the day-to-day work related to organizational ethics, in early 2022, we launched a national online survey of ethicists that attempted to describe the practice, scope and context of organizational ethics in health care.1 Of the 93 survey respondents, one third of them worked in Catholic health care.2

As explained in the survey, organizational ethics is an organization's efforts to "define its core values and mission, identify areas in which important values come into conflict, seek the best possible resolution of these conflicts and manage its own

performance to ensure that it acts in accord with espoused values."3 Upholding these standards is the responsibility of everyone in the organization, especially leaders, as their actions more directly influence the institution's decisions

and practices. Through greater understanding of the importance of the role of organizational ethics, Catholic health care leaders can help further the ministry's commitment to its mission and values.

SURVEY RESULTS

Of the survey's 14 questions, those most significant for Catholic health care leaders focused on the structure of organizational ethics in the system, areas of organizational ethics that respondents most frequently

encountered, the definition of organizational ethics and respondents' views on barriers to its success.

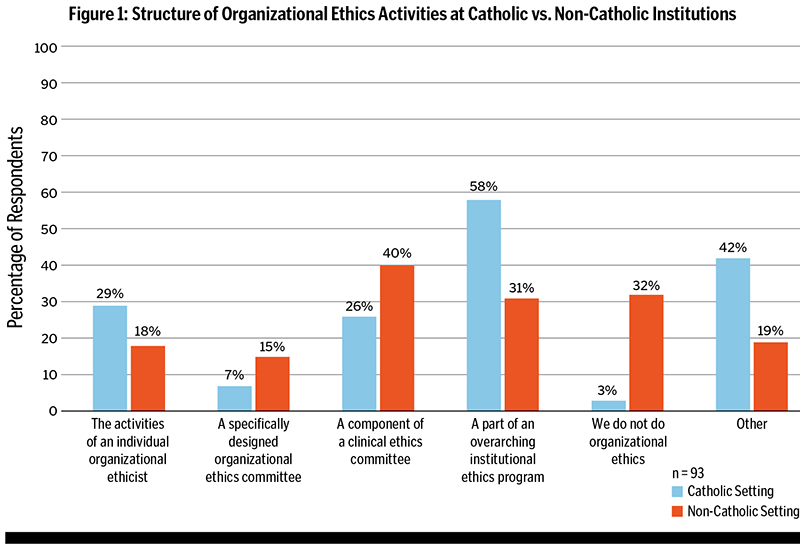

Structure of organizational ethics work in the ministry: The three most common structures reported by ethicists in Catholic health care are including organizational ethics as part of overarching institutional ethics programs (18, 58%),

employing an organizational ethicist (9, 29%) and including organizational ethics work in the responsibilities of a clinical ethics committee (8, 26%). (See Figure 1.) The "Other" responses mainly described mission integration work and discernment

as the main structure for organizational ethics. The data from non-Catholic health care was similar, except that the second highest response was that organizational ethics is not done in the respondent's institution (20, 32%).

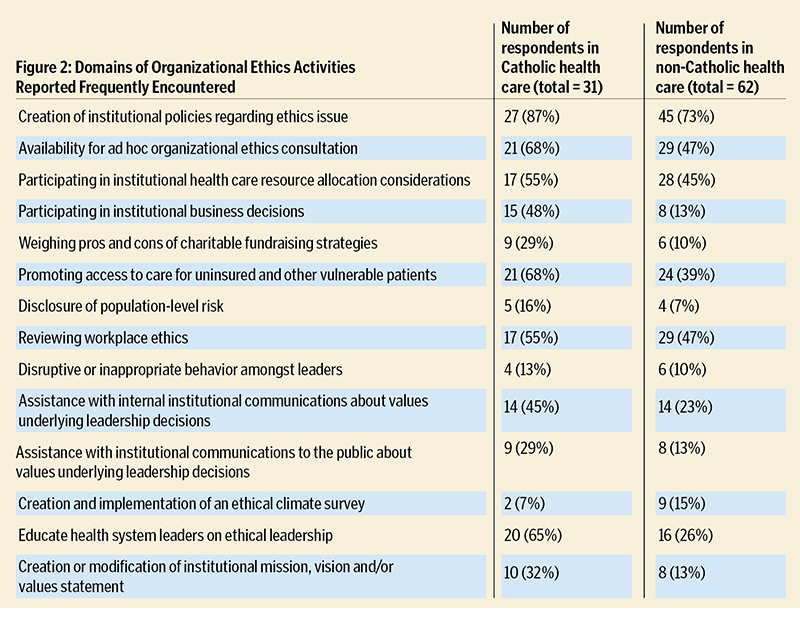

Areas of organizational ethics work most frequently encountered: The three most often encountered domains of organizational ethics work in Catholic health care are creating ethics-related policies, organizational ethics consultation regarding

a particular concern, and access to care for uninsured or other vulnerable patients. Again, responses from ethicists in non-Catholic systems were similar, except the domain of reviewing workplace ethics was tied with organizational ethics consultation

to round out the top three. (See Figure 2.)

Definition of organizational ethics: We asked respondents if their organization's definition of organizational ethics was different from the one used in the survey. Of those from Catholic health care systems, the most common answers include

12 who said their definition aligns with the one in the survey, six who responded that their institution had no definition of organizational ethics and five who said that their definition was different. Just four respondents reported no formal definition

at their system.

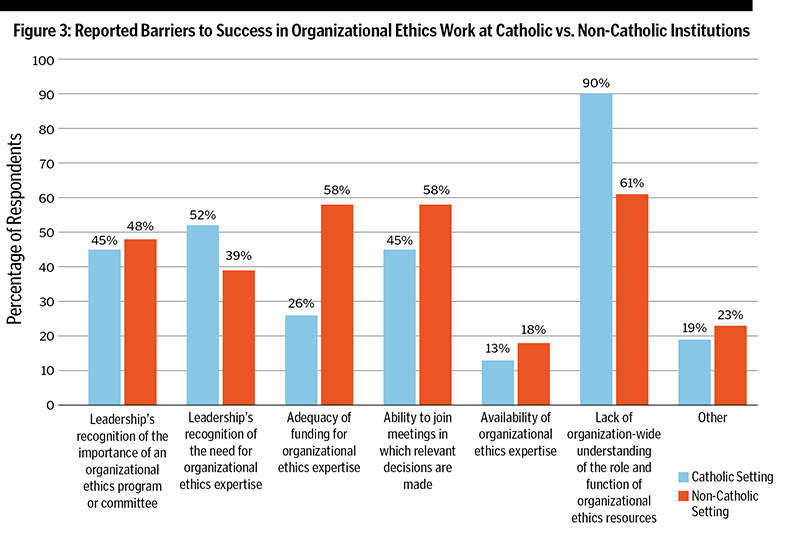

Barriers to success of organizational ethics: The three most commonly reported obstacles to successful organizational ethics work in Catholic health care are lack of systemwide understanding of the role and function of organizational

ethics, leadership's lack of recognition of the need for organizational ethics expertise, and a tie between the inability to join meetings in which relevant decisions are made and leadership's lack of recognition of the importance of an organizational

ethics program. Ethicists at non-Catholic facilities had similar responses for two of these barriers, and tied for the second most common barrier was the adequacy of funding for organizational ethics expertise (see Figure 3). Other barriers reported

by ethicists at Catholic facilities include scarcity of ethics resources, lack of time to meet the demand for organizational ethics work, referral of organizational ethics concerns late in the process (often due to the speed at which decisions are

made) and lack of clarity about what organizational ethics is.

KEY FINDINGS

This national survey of organizational ethicists identifies several points of interest to leaders in Catholic health care. First, organizational ethics appears to be more commonly acknowledged as an area of practice

in Catholic health systems. Only one ethicist (3%) at a Catholic facility reported they do not perform organizational ethics work, compared to 20 (32%) in non-Catholic hospitals. We suspect this may be due to the historical prominence of ethicists

and mission leaders at the highest levels of Catholic health ministries since mission integration began in the 1970s, in addition to the presence of ethicists even earlier.4 The role of a mission leader as an executive team member is in

part to work with leaders to ground their decisions and actions in the mission and values of the ministry.5

Second, the survey results show that Catholic health systems are twice as likely to include organizational ethics within a larger ethics program than as part of a clinical ethics committee. This could be due to the historical focus on organizational ethics

in Catholic health care, as the ministry has long used a discernment process to make operational decisions. Several sections of the Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services (ERDs), especially Part One and Part Six,

focus on organizational ethics, even if they do not use the term.6 On the one hand, such an approach that moves fluidly between clinical and organizational ethics may blur the lines between the two fields or lead to synergistic collaborations.

However, this would appear to explain why the results show that organizational ethics committees are comparatively rare in Catholic settings. This cohesive view of clinical and organizational ethics among Catholic ethicists could result in less focus

on resources specific to organizational ethics.

Third, Catholic ethicists were more likely than their non-Catholic counterparts to agree on which activities comprise organizational ethics work. Most Catholic ethicists agreed that they frequently encountered nearly half of the 14 assessed areas of organizational

ethics, compared to just one domain experienced by non-Catholic ethicists. Still, these results show that the field of organizational ethics has much work ahead to further define its scope. One respondent even stated, "I believe that the ambiguity

of the term 'organizational ethics' itself is the largest obstacle," when speaking to the success of this work.

Fourth, regarding barriers to success, Catholic respondents did not cite adequacy of funding nearly as highly as non-Catholics, and few respondents of any affiliation said that availability of expertise was an obstacle. Yet, as mentioned earlier, most

Catholic respondents described a lack of organizationwide understanding of organizational ethics as a barrier to success. They noted leadership's lack of recognition of its need and importance as other common hurdles. We interpret this to mean the

resources and expertise for organizational ethics are available in the Catholic ministries that responded, but leaders are unaware of when or how they can be helpful. The barriers reported in non-Catholic health care are markedly similar.

ENHANCING ORGANIZATIONAL ETHICS

Given this data, we offer four insights for leaders in Catholic health care:

1. Ethicists and leaders in Catholic health care should work together to increase familiarity and comfort around recognizing and requesting help with organizational ethics issues. This could be as simple as education on how and when an

ethicist or organizational ethics committee could help leaders. Most importantly, they need to embed organizational ethics questions, expertise and resources into the decision-making process. If this is standardized in the process, then a lack of

awareness should not be a concern. Such changes could also help avoid raising organizational ethics issues or seeking expert advice too late in the process. For example, if a new marketing campaign is ready for release, it is likely too late to consider

ethics or mission input or concerns.

2. Leaders should seek advice on ethical issues more frequently. Ethicists appear to see many organizational ethics issues that go unaddressed. This would likely explain why the top two reported barriers to success in organizational ethics

are a lack of understanding of its role and the need for this expertise. Leaders should not hesitate to reach out early to their ethicist (or, in some cases, mission leader), even when unsure if or how an ethicist could help. As one respondent said,

"The driven nature of health care moves teams well down a decision path before they realized they could have benefitted from pausing for a mission/organizational ethics discernment."

3. We need more scholarly publications centered on the work of organizational ethics, including in Catholic health care. While we might expect some structural variation in organizational ethics activities due to a system's unique needs,

the substantial diversity we found may be due to a lack of awareness of possible structures and how others do this work. For example, there is limited literature on what an organizational ethics committee is and how it works differently than one focused

on clinical ethics. The same is true for the organizational ethics work of a clinical ethics committee and an organizational ethicist. Even just a few published descriptions of these structures would go far toward strengthening the field.

4. Ethicists across Catholic health care should look to define the scope of organizational ethics work. Clarity on what is included and excluded from this field would help solidify it as a separate body of work worthy of dedicated resources

and attention. This could include an article, a consensus statement of interested parties or explicitly addressing the importance of organizational ethics in the ERDs. Part of this work should include a definition of organizational ethics with broad

agreement.

FURTHER GROWTH AHEAD

We acknowledge the limitations of this survey. Although this survey's small number of respondents may limit its findings about the practice of organizational ethics in Catholic health care as a whole, it does

appear that organizational ethics in the ministry is alive and well and that there is room for improvement. As we continue this research, we encourage Catholic health care ethicists, leaders and mission leaders to reflect on how they might use these

results and insights in their ministry. This work can begin by reflecting on a few questions:

- What is the structure for organizational ethics within my health system?

- Do I know when and how to request help with an organizational ethics issue?

- What can I do to help leaders understand how organizational ethics expertise can help them in their work?

- How am I being called to help organizational ethics grow and flourish in the areas I influence?

Through a better understanding of organizational ethics practices and its scope, future discussions can help lead to more institutional support, resources and training so the ministry can further continue its healing mission.

BECKET GREMMELS is system vice president of theology and ethics at CommonSpirit Health. KELLY TURNER is a mission intern at SSM Health and a doctoral student in health care ethics at Saint Louis University.

TIMOTHY LAHEY is an infectious disease physician and director of medical ethics at The University of Vermont Medical Center. WILLIAM NELSON is a professor and director of the ethics and human values program at Geisel

School of Medicine at Dartmouth College. JASON LESANDRINI is the assistant vice president of ethics, advance care planning and spiritual health at Wellstar Health System.

NOTES

- Kelly Turner et al., "Organizational Ethics in Healthcare: A National Survey," HEC Forum 36, no. 1 (January 17, 2024): https://doi.org/10.1007/s10730-023-09520-3.

The Dartmouth College Institutional Review Board (Dartmouth Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects) approved this research protocol for exemption from further review under Category II.

- We don't have a total number of those working in organizational ethics in U.S. health care. Ethicists who were invited to take the survey included those at the American Society for Bioethics and the Humanities' Organizational Ethics Affinity Group

and the Clinical Ethics Consultation Affinity Group, the Medical College of Wisconsin bioethics listservs, as well as a list of ethicists working at Catholic institutions and Seventh-day Adventist institutions. Of the survey respondents who worked

in Catholic health care, eight had mission in their title. Of those, three had a doctorate in bioethics, one completed an ethics fellowship, one had an ethics certificate from the National Catholic Bioethics Center and another had the health care

ethics consultant certification from the HCEC Certification Commission. Four of these also had mission and ethics in their title. Of the two who did not have formal ethics training, both had gone through significant ethics education. Additionally,

19 of those who worked in Catholic health care said they worked in a system office; eight in a hospital; two in an academic medical center; and two at the regional level.

- Steven Pearson, James Sabin, and Ezekiel Emanuel, No Margin, No Mission: Health Care Organizations and the Quest for Ethical Excellence (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 32.

- Brian Smith, "Form Follows Function: The Evolution of Mission Integration in U.S. Catholic Health Care," Health Progress 101, no. 2 (March/April 2020): 51-60.

- Patrick McCruden and Mark Kuczewski, "Is Organizational Ethics the Remedy for Failure to Thrive? Toward an Understanding of Mission Leadership," HEC Forum 18, no. 4 (December 2006): 342.

- For example, see the general introduction and Directives 7, 9, 11 and 22: Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services: Sixth Edition (Washington, DC: United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2018).